Amazon: Longest River in the World

Plot

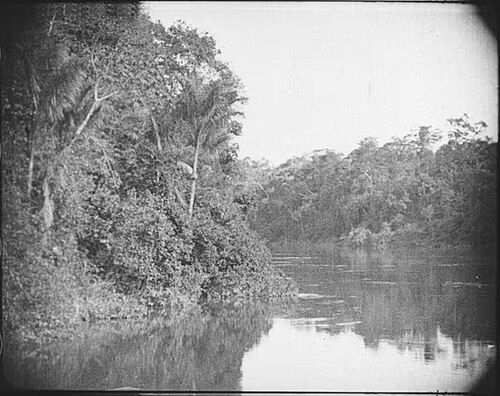

This pioneering 1918 documentary takes viewers on an extraordinary journey through the Amazon basin, capturing the region's stunning biodiversity and the lives of its Indigenous inhabitants. Director Silvino Santos masterfully alternates between intimate close-up shots of exotic wildlife including caimans, jaguars, and tropical flora, with longer sequences documenting the extractive industries that dominated the region's economy. The film features some of the earliest known moving images of the Indigenous Witoto people, showcasing their traditional rituals and daily life with unprecedented ethnographic detail. Through comprehensive footage of rubber tapping, Brazil nut harvesting, timber operations, fishing, and even egret feather collection for women's fashion, the documentary presents both the natural wonders of the Amazon and the complex relationship between its resources and human exploitation during the early 20th century rubber boom era.

Director

About the Production

Silvino Santos undertook this ambitious documentary project during the height of the Amazon rubber boom, spending approximately two years filming in extremely challenging conditions. The production required navigating difficult terrain through dense rainforest, dealing with tropical diseases, and transporting heavy camera equipment by boat and on foot. Santos developed relationships with Indigenous communities to gain their trust and permission to film sacred rituals and daily activities. The crew had to combat the extreme humidity that threatened film equipment and stock, often developing footage on-site in portable darkrooms to prevent spoilage. Many wildlife sequences required days of patient waiting in carefully constructed camera hides to capture the intimate animal footage that distinguishes this documentary.

Historical Background

This documentary was produced during the final years of the Amazon rubber boom, a period that had dramatically transformed the region economically, socially, and environmentally. World War I was raging across Europe, creating unprecedented demand for Amazonian rubber for military applications including tires, gas masks, and other essential equipment. The documentary captured a pivotal moment when traditional Indigenous ways of life were rapidly changing due to increased contact with the rubber industry and the outside world. Brazil was undergoing significant modernization under President Venceslau Brás, and there was growing international interest in the Amazon's vast natural resources and economic potential. The film emerged during the early golden age of documentary filmmaking, when pioneers like Robert Flaherty were establishing ethnographic cinema as a legitimate art form. It also coincided with the height of colonial exploration narratives, though Santos's approach was notably more respectful and observational toward Indigenous peoples than many contemporary expedition films that often exploited or sensationalized native cultures.

Why This Film Matters

This documentary represents a crucial milestone in both Brazilian cinema history and the development of anthropological filmmaking, standing as one of the first comprehensive visual records of the Amazon region and its diverse Indigenous peoples. It established an influential template for subsequent Amazon documentaries and inspired generations of filmmakers interested in ethnographic subjects and natural history. The film's relatively respectful portrayal of Indigenous communities was progressive for its era, avoiding the sensationalism and exploitation common in many contemporary expedition and travel films. It serves as an invaluable time capsule of Amazonian ecosystems before extensive deforestation and development, capturing species, landscapes, and cultural practices that have since been altered or disappeared entirely. The documentary also played a significant role in raising international awareness about the Amazon's ecological importance and the complex relationship between economic exploitation and cultural preservation. Its rediscovery and restoration in the late 20th century have contributed to modern understanding of early 20th-century Amazon history, the rubber boom era, and the evolution of documentary filmmaking techniques worldwide.

Making Of

Silvino Santos began this ambitious documentary project around 1916, assembling a small but dedicated team that included himself as principal cinematographer, local guides familiar with the territory, and numerous porters to carry the heavy equipment through challenging Amazonian terrain. The production required extensive advance planning and negotiations, as Santos had to coordinate with various rubber plantation owners and Indigenous tribal leaders to gain access to remote filming locations. Many of the wildlife sequences were captured using sophisticated baiting techniques and carefully positioned camera hides, with Santos sometimes waiting for days in extreme conditions to obtain the perfect shot. The footage of Indigenous rituals proved particularly challenging to obtain, as Santos had to first establish trust through careful diplomacy, gift-giving, and demonstrating genuine respect for tribal customs and sacred practices. The film's editing process took nearly six months in Rio de Janeiro, where Santos worked meticulously to create a narrative flow that balanced natural history documentation with ethnographic content. The production faced numerous setbacks including equipment failures in the oppressive humidity, multiple cases of malaria and other tropical diseases among crew members, and the constant threat of animal attacks during filming in isolated locations far from medical help.

Visual Style

Silvino Santos employed innovative cinematographic techniques that were remarkably advanced for 1918, including the sophisticated use of telephoto lenses for wildlife photography and pioneering attempts at underwater filming in the murky Amazonian rivers. The camera work demonstrates extraordinary mobility considering the heavy and cumbersome equipment limitations of the era, with fluid tracking shots following canoes through narrow river channels and smooth panning movements capturing the immense scale and verticality of the rainforest canopy. Santos utilized natural lighting with exceptional skill, particularly in sequences filmed within Indigenous villages where he worked creatively with available light filtering through thatched roof openings and jungle canopy. The close-up photography of animals and plants was particularly innovative for its time, revealing intricate details of Amazonian flora and fauna that had never before been captured on film with such clarity and intimacy. The documentary features some of the earliest successful examples of time-lapse photography in nature documentary, showing the rapid blooming of tropical flowers and the dramatic movement of storm clouds over the forest canopy, techniques that would not become common in documentary filmmaking for decades.

Innovations

This documentary pioneered several significant technical innovations in location filmmaking, including the development of specially modified portable camera equipment suitable for the extreme conditions of tropical rainforest environments. Santos designed and built custom waterproof housing for his cameras, allowing for filming in and around Amazonian rivers during the intense rainy season when water levels rose dramatically. The production overcame formidable technical challenges including preventing fungus and mold growth on valuable film stock in the oppressive humidity, developing methods to keep delicate camera mechanisms functioning in extreme heat and moisture, and creating portable developing solutions to process footage on-site before it could spoil. The film features some of the earliest successful applications of color tinting techniques used to enhance natural scenes, with blue tints for water sequences, amber and green tones for jungle footage, and red filters for dramatic sunset sequences. The documentary also demonstrated advances in editing techniques, with Santos creating remarkably smooth transitions between different types of footage to maintain narrative flow and emotional impact. The very survival of the film stock itself represents a significant technical achievement, as the vast majority of films from this era have been lost due to the unstable and highly flammable nature of early celluloid nitrate film.

Music

As a silent film produced in 1918, 'Amazon: Longest River in the World' would have been accompanied by live musical performances during its original theatrical runs, as was standard practice for cinema of this era. The typical musical accompaniment would have included classical pieces carefully selected and adapted to match the on-screen action, with Brazilian folk melodies and traditional Indigenous-inspired music used during sequences featuring native peoples and their rituals. Major city screenings in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo likely employed small orchestras that could provide dynamic and nuanced accompaniment, while smaller venues and traveling shows would have used skilled piano accompanists. Modern restorations and special screenings have been paired with newly composed scores that attempt to evoke the authentic atmosphere of the Amazon while respecting the film's historical context and avoiding cultural appropriation. The original musical cues and specific composition credits, if any existed, have been lost to time, as was common with silent films of this period where music was often improvised or adapted locally for each screening.

Famous Quotes

The Amazon, mother of all rivers, reveals her secrets only to those who approach with respect and infinite patience

In the heart of the jungle, time flows differently, measured by seasons and cycles rather than clocks and calendars

The Indigenous peoples of the Amazon hold ancient wisdom that modern man has forgotten in his desperate rush for progress and profit

To truly understand the Amazon, one must listen not only with ears but with heart and spirit

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic opening sequence following a dugout canoe through narrow Amazonian waterways at dawn, with ethereal mist rising from the water and exotic birds calling from the dense canopy overhead

- The intimate and unprecedented close-up footage of a jaguar drinking cautiously from a river bank, captured using a carefully concealed camera position that required weeks of patient waiting

- The extended sequence of Witoto tribal rituals, featuring elaborate traditional body painting, ceremonial dances, and authentic music using ancient instruments passed down through generations

- The comprehensive rubber tapping sequence showing the complex and dangerous process of collecting and processing latex, with workers moving with practiced skill through the forest at night

- The revolutionary underwater photography sequence revealing the diverse fish species, aquatic plants, and river life of Amazon waters, absolutely groundbreaking for its time and technical achievement

Did You Know?

- This film contains some of the earliest known moving images of the Witoto people, making it invaluable for anthropological study and cultural preservation

- Director Silvino Santos was born in Portugal but immigrated to Brazil, where he became one of the country's pioneering documentary filmmakers

- The film was originally titled 'No País das Amazonas' (In the Land of the Amazons) in Portuguese before receiving its English title

- Santos risked his life multiple times during filming, including dangerous encounters with wildlife and initially hostile Indigenous groups suspicious of his camera

- The footage of rubber tapping operations documented the absolute height of the Amazon rubber boom, capturing an economic system that would collapse completely within a few years

- Some sequences were staged for dramatic effect, a common practice in early ethnographic films, though most wildlife and ritual footage was authentic documentary material

- The film was considered lost for decades before a copy was discovered in European archives in the 1970s

- Santos used innovative camera techniques for the time, including some of the earliest attempts at underwater photography in Amazonian rivers

- The documentary was initially banned or censored in some European countries for its depiction of Indigenous nudity and tribal rituals

- Modern digital restoration has revealed details and textures that were not visible in original 1918 screenings due to the limitations of projection technology

- The egret feather footage documents a fashion industry that would soon be revolutionized by conservation movements and synthetic alternatives

- Santos carried approximately 500 pounds of camera equipment and film stock through the Amazon, an incredible feat for the era

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its remarkable technical achievements and the unprecedented access it provided to remote Amazon regions rarely seen by outside eyes. Brazilian newspapers hailed it as a national triumph that showcased the country's extraordinary natural wonders and cultural diversity to the world. International reviewers were particularly impressed by the wildlife sequences, with some comparing Santos's work favorably to that of more famous African expedition films while noting its superior ethnographic sensitivity. Modern critics have reevaluated the documentary as a significant ethnographic document of immense historical value, though some note the problematic aspects inherent in filming Indigenous peoples during the colonial era. The film is now recognized by film historians as a pioneering work that successfully balanced entertainment value with documentary authenticity, though some sequences are acknowledged as having been staged for dramatic effect, a common practice of the period. Recent restoration efforts have led to renewed appreciation for Santos's sophisticated cinematographic skills and his relatively sensitive approach to cross-cultural documentation for his time.

What Audiences Thought

The film was initially popular with Brazilian audiences who were fascinated to see remote regions of their vast country depicted on screen for the first time, creating a sense of national pride and wonder. International audiences were drawn to the exotic imagery and sense of adventure, with the documentary enjoying successful runs in several European capitals where Amazonia was regarded as a mysterious and dangerous paradise. Some viewers were shocked by the frank depictions of Indigenous nudity and authentic tribal rituals, leading to occasional censorship in more conservative markets and demands for cuts to controversial sequences. Modern audiences viewing the restored version often express fascination with the incredible historical record it provides, though some contemporary viewers critique the colonial gaze and power dynamics inherent in the filming process. The documentary continues to be screened at film festivals, academic conferences, and museum retrospectives, where it generates thoughtful discussion about early ethnographic filmmaking practices, representation of Indigenous peoples in cinema, and the changing ethics of documentary documentation over the past century.

Awards & Recognition

- Gold Medal, Brazilian Exposition of 1919

- Honorary Mention, International Geographic Congress, 1920

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Scientific expedition literature of the 19th century

- Works of naturalist Alexander von Humboldt

- Robert Flaherty's ethnographic approach (though 'Nanook' came later)

- Expedition films and travelogues of the early 20th century

- Ethnographic photography and anthropological studies of the period

- Brazilian literary traditions of regionalism and nature writing

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Amazon documentaries by various directors throughout the 20th century

- Brazilian documentary tradition and cinema novo movement

- Ethnographic films of the 1920s-1930s

- Nature documentary genre development and evolution

- Modern Amazon conservation and environmental documentaries

- Indigenous rights documentary filmmaking

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for several decades before a remarkably complete print was discovered in the Cinematheque Francaise archives in Paris during the 1970s. A major restoration project undertaken in the 1990s, funded by Brazilian cultural institutions and international film preservation organizations, resulted in a preserved version that maintains much of the original visual quality and detail. The restored version has been subsequently digitized using modern technology and is carefully maintained by the Cinemateca Brasileira in São Paulo as part of Brazil's national cinematic heritage. Some original footage remains missing or damaged, particularly certain sequences that were censored or cut from various initial releases in different countries. The film is now officially recognized as part of Brazil's national cultural patrimony, and ongoing preservation efforts continue to improve the quality and accessibility of available copies for scholarly and public viewing. Multiple archives worldwide now hold preservation copies of the restored version, ensuring the film's long-term survival for future generations of researchers, filmmakers, and audiences.