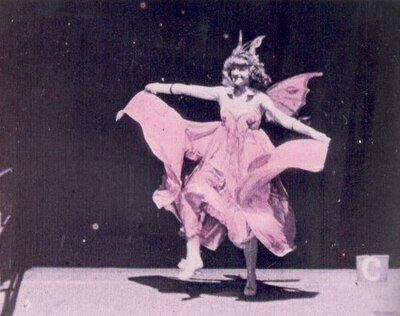

Annabelle Butterfly Dance

Plot

Annabelle Moore, one of the most famous dancers of the 1890s, performs her signature butterfly dance in this groundbreaking short film. Wearing a costume with delicate wings attached to her back, she gracefully moves across the stage while manipulating her long, flowing skirts to create mesmerizing visual patterns. The performance captures the essence of the popular serpentine dance style that captivated audiences during the Gilded Age. Moore's elegant movements and the flowing fabric create an ethereal effect that showcases both her artistic talent and the new possibilities of motion picture technology. The entire performance is a testament to the early cinema's fascination with capturing movement and spectacle.

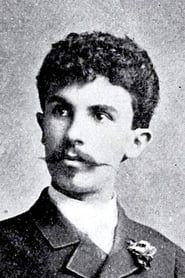

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in Edison's revolutionary Black Maria studio, which was designed with a retractable roof to utilize natural sunlight. The studio was built on a circular turntable that could be rotated to follow the sun's path throughout the day. Annabelle Moore was one of Edison's most popular performers, commanding higher fees than other dancers. The butterfly wings were a special costume addition to distinguish this performance from her other serpentine dances. The film was shot on 35mm film using Edison's Kinetograph camera, which was so heavy it had to be bolted to the floor.

Historical Background

1894 was a revolutionary year in entertainment history. Thomas Edison had just unveiled his Kinetoscope peep-show viewing machines, and the public was fascinated by this new technology that could bring moving images to life. The Gilded Age was in full swing, with America experiencing unprecedented industrial growth and cultural change. Vaudeville theaters were at their peak of popularity, and dance performances like Moore's were among the most sought-after attractions. The film was created during a period of intense technological innovation, with electricity becoming widespread and new forms of entertainment emerging. This was also the era when photography was transitioning from a scientific curiosity to an art form, and motion pictures represented the next frontier in visual media.

Why This Film Matters

'Annabelle Butterfly Dance' holds immense cultural significance as one of the earliest examples of dance on film and a pioneering work in establishing cinema as an art form. The film helped demonstrate that motion pictures could do more than simply document reality - they could capture and enhance artistic performance. It represents the intersection of Victorian-era dance culture with emerging technology, showing how new media can transform traditional art forms. The film also established the template for using cinema to showcase spectacle and movement, a foundation upon which the entire dance film genre would be built. Additionally, it marked one of the first instances of a performer becoming famous specifically through motion pictures, presaging the star system that would dominate Hollywood for decades.

Making Of

The making of 'Annabelle Butterfly Dance' represents a pivotal moment in cinema history. William K.L. Dickson, Edison's chief engineer, had just perfected the Kinetograph camera and was eager to demonstrate its capabilities. The choice to film dancers was strategic - their movements showcased the medium's unique ability to capture motion in ways photography never could. Annabelle Moore was discovered by Edison scouts while performing at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The filming process was grueling by modern standards - Moore had to perform repeatedly under the hot studio lights, and the camera noise required her to dance to silent cues rather than music. The butterfly costume was specially designed for this performance, with lightweight materials that would flow beautifully during the dance but not obscure Moore's movements from the camera's fixed position.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Annabelle Butterfly Dance' was revolutionary for its time, utilizing the newly perfected Kinetograph camera. The fixed camera position, typical of early films, creates a stage-like presentation that emphasizes Moore's full-body movements. The lighting, provided solely by natural sunlight through the Black Maria's retractable roof, creates a soft, naturalistic quality that enhances the ethereal nature of the performance. The camera's ability to capture the flowing movement of Moore's skirts and wings demonstrated the unique power of motion pictures to document motion. The 35mm film format provided sufficient detail to render the delicate patterns created by the dancer's costume, showcasing the technical capabilities of Edison's system.

Innovations

'Annabelle Butterfly Dance' showcased several groundbreaking technical achievements. The film was shot using Edison's Kinetograph camera, which had just been perfected in 1893 and could capture continuous motion at 40 frames per second. The Black Maria studio where it was filmed featured innovative design elements including a retractable roof for natural lighting and a rotating base to follow the sun's movement. The 35mm film format established by Edison would become the industry standard for decades. The film also demonstrated early understanding of how camera positioning could best capture dance movement, establishing techniques that would influence dance cinematography for generations. The ability to capture flowing fabric and rapid movement represented a significant advancement in motion picture technology.

Music

The original film was silent, as all early Kinetoscope productions were. When exhibited, the films were often accompanied by live music provided by the venue, typically a pianist or small orchestra. The music would have been popular tunes of the 1890s chosen to complement the mood of the performance. Some modern restorations have added period-appropriate music to enhance the viewing experience. The absence of synchronized sound was actually advantageous for dance films, as it allowed venues to adapt the musical accompaniment to local tastes and the specific atmosphere of each exhibition space.

Famous Quotes

'A marvel of modern science' - The New York Sun (1894)

'The moving pictures bring Miss Moore's performance to life with startling realism' - Edison Gazette (1894)

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Annabelle Moore first spreads her butterfly wings, creating a stunning visual effect that immediately captivates viewers and showcases the magical quality of early cinema

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first films to feature a named performer, helping establish the concept of film 'stars'

- Annabelle Moore was only 16-17 years old when she filmed this performance

- The film was shot at 40 frames per second, much faster than modern films, making the original playback appear jerky

- Moore was paid $35 per week by Edison, a substantial salary for the time

- The Black Maria studio where this was filmed was the world's first movie production studio

- This film was part of a series of dance films Edison produced to showcase the Kinetoscope

- The butterfly dance was inspired by the popular serpentine dance created by Loie Fuller

- The film was hand-colored in some releases to enhance the visual effects

- Annabelle Moore later became a Broadway star and appeared in Ziegfeld productions

- The original film negative was destroyed in a 1914 Edison laboratory fire

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception to 'Annabelle Butterfly Dance' was overwhelmingly positive, with newspapers and magazines marveling at the lifelike quality of the moving images. The New York Sun described it as 'a marvel of modern science' that captured Moore's performance with 'startling realism.' Edison's trade publications promoted it heavily as evidence of their technological superiority. Modern critics recognize it as a landmark film that demonstrated early cinema's artistic potential beyond mere documentation. Film historians view it as a crucial step in the evolution of cinema from novelty to art form, particularly in how it used the new medium to enhance rather than simply record performance.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1894 were absolutely captivated by 'Annabelle Butterfly Dance' and similar Kinetoscope films. The experience of seeing moving images for the first time was magical to Victorian-era viewers, who lined up at penny arcades to peer into Edison's viewing machines. The dance films were particularly popular because they showcased movement in ways that static photographs never could. Contemporary accounts describe viewers gasping and applauding as they watched Moore's flowing skirts create patterns on screen. The film's popularity helped establish the commercial viability of motion pictures and encouraged Edison to produce more dance and performance films. Modern audiences viewing the film today often express fascination with its historical significance and the elegant simplicity of its presentation.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Loie Fuller's serpentine dance performances

- Victorian-era stage shows

- Burlesque and vaudeville traditions

- Photographic motion studies by Eadweard Muyvey

This Film Influenced

- Annabelle Serpentine Dance (1894)

- Trapeze Disrobing Act (1901)

- The Great Train Robbery (1903)

- Early Hollywood dance films

- Music video aesthetics

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in various archives including the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. Multiple copies exist, though some show varying degrees of deterioration. The original Edison negative was destroyed in a 1914 fire, but duplicate negatives and prints survived. The film has been digitally restored by several institutions and is available in high-quality versions. Some hand-colored versions from the 1890s also survive, showing how early exhibitors enhanced the visual experience.