Arrival of a Train at Perrache

Plot

This early documentary short captures the precise moment when a steam locomotive arrives at Perrache station in Lyon, France. The train pulls into the platform and gradually comes to a stop, with steam billowing from its engine. Passengers begin to disembark from the train cars, stepping onto the platform while others wait to board. The entire scene unfolds in a single continuous shot, documenting the everyday activity of train travel in late 19th century France. The film concludes as the platform becomes more crowded with people moving about their business.

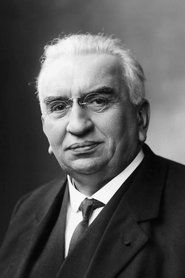

Director

About the Production

Filmed using the Lumière Cinématographe, which served as both camera and projector. The camera was positioned on the platform to capture the train's arrival from a side angle. This was one of many actualité films (documentary shorts of everyday life) that the Lumière brothers produced to demonstrate their invention. The station was a major transportation hub in Lyon, making it an ideal location for capturing the movement and modernity that fascinated early filmmakers.

Historical Background

This film was created during the dawn of cinema, just one year after the Lumière brothers held their first public screening on December 28, 1895, at the Grand Café in Paris. The 1890s were a period of tremendous technological innovation, with the Industrial Revolution having transformed transportation through the expansion of railway networks across Europe. Lyon, where this film was made, was a major industrial center and the home of the Lumière family's photographic plate factory. The film captures the essence of the Belle Époque, a period of relative peace and prosperity in France characterized by technological progress, artistic innovation, and urban modernization. The arrival of cinema coincided with other revolutionary inventions including the automobile, telephone, and electric lighting, all of which were reshaping daily life. The railway itself was a symbol of modernity and progress, connecting cities and facilitating the movement of people and goods in ways previously unimaginable.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the earliest motion pictures ever created, 'Arrival of a Train at Perrache' represents a fundamental moment in human cultural history - the birth of cinema as a medium for documenting reality. This film exemplifies the Lumière brothers' philosophy that cinema's primary value lay in its ability to capture and preserve moments of real life, contrasting with Georges Méliès' contemporary approach of using film for fantasy and trick effects. The film helped establish the documentary tradition in cinema and demonstrated the power of moving images to transport viewers across space and time. It represents the beginning of visual storytelling and the democratization of image-making, as the Lumière brothers trained numerous cameramen who spread their technology and techniques worldwide. The simple act of filming a train's arrival may seem mundane today, but in 1896, it was nothing short of magical, offering audiences their first glimpse of captured reality in motion. This film and others like it established conventions that would influence documentary filmmaking for over a century.

Making Of

The filming of 'Arrival of a Train at Perrache' was part of the Lumière brothers' systematic documentation of everyday life using their revolutionary Cinématographe device. Louis Lumière, who had a background in photography and chemistry, personally directed and filmed many of these early actualités. The camera was set up on a tripod on the station platform, requiring careful timing to capture the train's arrival. The entire film was shot in one continuous take, as editing techniques had not yet been developed. The Lumière factory in Lyon produced both the camera and the film stock used for this production. The brothers would often film in the morning when light was optimal, and this particular film likely required coordination with the railway schedule to ensure the train's arrival coincided with filming. The steam locomotive and its passengers were completely unaware they were being filmed, contributing to the authentic documentary quality that characterized Lumière productions.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Arrival of a Train at Perrache' exemplifies the earliest principles of film photography, characterized by a single, stationary camera position and continuous shot. The film was shot using the Lumière Cinématographe, which utilized a claw mechanism to advance the film intermittently, creating smooth motion at approximately 16 frames per second. The camera was placed at eye level on the platform, creating a natural perspective that would have been familiar to railway passengers of the time. The composition places the train diagonally across the frame, creating a sense of depth and movement that was sophisticated for its era. Natural lighting was used exclusively, as artificial lighting for film had not yet been developed. The black and white images display remarkable clarity and detail, showcasing the quality of Lumière's film stock and lens design. The fixed camera position and long take style would become characteristic of early cinema and reflected the Lumière brothers' documentary approach to filmmaking.

Innovations

This film showcases several groundbreaking technical achievements of early cinema. The Lumière Cinématographe used for filming was revolutionary in its design, serving as camera, developer, and projector in one device. The film employed 35mm film with perforations, a format that would become the industry standard for over a century. The intermittent movement mechanism, using a claw to advance the film frame by frame, created smoother motion than earlier devices. The projection system was bright enough to be viewed by large audiences, a significant improvement over Thomas Edison's Kinetoscope which could only be viewed by one person at a time. The film's preservation of motion at 16 frames per second established a baseline for frame rates in early cinema. The portable nature of the Cinématographe (weighing only 5 kg) allowed for filming in actual locations rather than studio settings, revolutionizing the possibilities for documentary filmmaking.

Music

The film was originally presented as a silent work, as synchronized sound technology would not be developed until the late 1920s. During initial exhibitions, musical accompaniment was typically provided by a pianist or small ensemble who would improvise appropriate music to match the on-screen action. For a film like 'Arrival of a Train at Perrache,' musicians might have played popular songs of the era, classical pieces, or specially composed train-themed music. Some venues employed sound effects artists who would create noises to enhance the viewing experience, such as whistling sounds to accompany the train's arrival. Modern restorations and presentations of the film sometimes include newly composed scores or period-appropriate music to recreate the experience of early cinema exhibitions.

Famous Quotes

"The cinema is an invention without a future." - Louis Lumière (ironically, despite his pioneering work)

"My invention can be exploited... as a scientific curiosity, but it has no commercial value whatsoever." - Auguste Lumière, 1895

Memorable Scenes

- The moment the steam locomotive first enters the frame, billowing white smoke as it approaches the platform, with passengers visible through the train windows, creating a powerful image of 19th-century transportation and human movement

Did You Know?

- This is one of the earliest films ever made, coming just one year after the Lumière brothers' first public screening in 1895

- Perrache station was named after Antoine-Michel Perrache, who developed the area in the 18th century

- The film was shot on 35mm film at approximately 16 frames per second

- Louis Lumière personally operated the camera for many of these early actualité films

- The train featured was likely a Chemin de fer de Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée (PLM) railway company locomotive

- This film is often confused with the more famous 'Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat' (1895), also by the Lumière brothers

- The Cinématographe camera used for this film weighed only 5 kilograms, making it highly portable for its time

- Early audiences were reportedly fascinated by the realistic depiction of motion on screen

- The film was part of the Lumière brothers' initial catalog of approximately 1,422 short films

- Perrache station is still operational today, though it has been extensively modernized since 1896

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception of Lumière films like 'Arrival of a Train at Perrache' was overwhelmingly positive, with audiences and critics marveling at the technological achievement of capturing and reproducing motion. Newspapers of the era described the exhibitions as 'living photographs' and 'miracles of science.' Critics noted the unprecedented realism and immediacy of the images, with many commenting on how the films seemed to bring the world directly to the viewer. Modern film historians recognize this work as a foundational text of cinema, praising its simplicity, directness, and historical importance. Scholars have noted how these early actualités established cinema's unique ability to document reality, a capability that would later become central to documentary filmmaking. The film is frequently cited in film studies courses as an example of early cinema's observational style and the Lumière brothers' contribution to establishing the basic grammar of film language.

What Audiences Thought

Early audiences reportedly reacted with astonishment and excitement to Lumière films, with some viewers allegedly ducking or moving away from the screen when the train appeared to be coming toward them (though this apocryphal story is more commonly associated with 'Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat'). The exhibitions were enormously popular, drawing crowds of curious spectators eager to experience this new technological marvel. Working-class audiences were particularly fascinated by seeing familiar scenes of daily life reproduced on screen, while middle-class viewers were drawn to the scientific and technological aspects of the invention. The films were typically shown as part of a program of 10-20 short subjects, each lasting less than a minute, with 'Arrival of a Train at Perrache' being one of the popular selections. Audience members often returned multiple times to see the same films, suggesting that the novelty and wonder of moving images held enduring appeal despite the simplicity of the subjects.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Eadweard Muybridge's motion studies

- Étienne-Jules Marey's chronophotography

- Thomas Edison's Kinetoscope films

- Still photography

- Railway travel posters and art

This Film Influenced

- Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1895)

- The Kiss (1896)

- Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (1895)

- A Trip to the Moon (1902)

- The Great Train Robbery (1903)

- Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and is part of the Lumière Institute's collection in Lyon, France. Multiple copies exist in film archives worldwide, including the Cinémathèque Française, the Library of Congress, and the British Film Institute. The film has been digitally restored and is available in high-quality formats, ensuring its survival for future generations. As one of the most important early films, it has received careful preservation attention from film archives and historians.