Artistic Creation

Plot

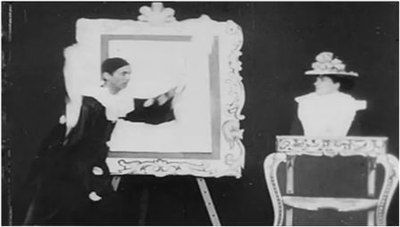

In this pioneering trick film, an artist begins by sketching the head of a pretty woman on paper. He then removes the drawn head from the paper and places it on a table, where it transforms into a real three-dimensional head. The artist continues his magical creation by drawing each body part sequentially - the neck, shoulders, arms, torso, and legs - with each drawn element materializing into reality and assembling itself to form a complete living woman. The completed figure then comes to life, moving and bowing before the astonished artist, showcasing the magical possibilities of early cinematic special effects.

Director

Cast

About the Production

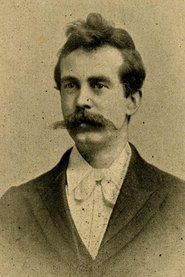

This film was created using stop-motion techniques and substitution splicing, which were revolutionary special effects methods for 1901. Walter R. Booth, who both directed and starred in the film, was known for his innovative trick films that pushed the boundaries of what was possible in early cinema. The film was likely shot in a single day due to the technical limitations of early film equipment and the complexity of the stop-motion effects required.

Historical Background

1901 was a pivotal year in early cinema, occurring just six years after the Lumière brothers' first public film screening in 1895. The film industry was still in its experimental phase, with filmmakers exploring the creative possibilities of the new medium. Queen Victoria's reign ended in 1901, marking the transition from the Victorian to the Edwardian era in Britain. This period saw rapid technological advancement and growing public fascination with moving pictures. Films were typically shown in music halls, fairgrounds, and temporary exhibition spaces rather than dedicated cinemas. The British film industry, led by pioneers like Robert W. Paul, was competing with French and American filmmakers who were also pushing the boundaries of cinematic storytelling and special effects.

Why This Film Matters

'Artistic Creation' represents an important milestone in the development of cinematic special effects and animation. As one of the earliest examples of stop-motion technique, it demonstrated film's unique ability to bring inanimate objects to life - something impossible in live theater. The film's theme of creation through art reflected contemporary fascination with scientific discovery and the boundaries between reality and illusion. It helped establish the vocabulary of visual effects that would become fundamental to cinema, influencing countless future filmmakers. The film also exemplifies the Victorian fascination with spiritualism and the supernatural, themes that were popular in entertainment of the period.

Making Of

The creation of 'Artistic Creation' required meticulous planning and execution. Walter R. Booth, drawing on his background as a magician, understood the importance of precise timing and visual illusion. The film was shot using a hand-cranked camera, and each frame had to be carefully composed to create the seamless illusion of the drawing coming to life. The actress playing the created woman had to remain perfectly still while Booth photographed each stage of her 'creation,' moving only slightly between takes to simulate the gradual assembly of her body. The substitution splicing technique involved stopping the camera, making changes to the scene, then restarting filming to create instantaneous transformations that appeared magical to contemporary audiences.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Artistic Creation' was pioneering for its time, utilizing multiple exposures and substitution splicing to create the illusion of transformation. The camera work was static, as was typical of early films, but the composition within the frame was carefully planned to maximize the impact of the special effects. The lighting was bright and even to ensure clear visibility of the magical transformations. The film used close-up shots to emphasize the drawing process and the gradual assembly of the human figure, which was innovative for a period when most films used wide shots exclusively.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was its pioneering use of stop-motion animation and substitution splicing. These techniques allowed for the seamless transformation of 2D drawings into 3D reality, a feat that amazed contemporary audiences. The film demonstrated early mastery of special effects that would become standard in cinema, including careful frame-by-frame photography and precise editing to create impossible illusions. The successful integration of live action with animated elements was particularly innovative for 1901, predating more famous examples of similar techniques by several years.

Music

As a silent film from 1901, 'Artistic Creation' had no synchronized soundtrack. During exhibition, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra in music halls. The musical accompaniment would have been chosen to match the mood of each scene - playful during the drawing process, magical during the transformations, and triumphant when the completed figure comes to life. The specific musical selections would have varied by venue and performer, as was common with early cinema exhibition.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, 'Artistic Creation' contains no spoken dialogue or famous quotes.

Memorable Scenes

- The magical moment when the artist removes the drawn head from the paper and it transforms into a real three-dimensional head, demonstrating the film's innovative special effects and establishing the theme of artistic creation coming to life.

Did You Know?

- Walter R. Booth was a former magician who brought his knowledge of illusion to filmmaking, making him particularly suited to create trick films like this one.

- The film was produced by Robert W. Paul, one of Britain's earliest film pioneers and inventors who ran a successful film production company.

- At only one minute long, this film was typical of the duration of early films, which were often shown as part of variety programs alongside live performances.

- The technique of bringing drawings to life through stop-motion would later be perfected by animators like Willis O'Brien and Ray Harryhausen.

- This film is considered one of the earliest examples of stop-motion animation in cinema history.

- The transformation effects were achieved through careful frame-by-frame photography and substitution splicing techniques.

- Walter R. Booth created over 100 short films between 1899 and 1915, many of which featured similar magical transformations and trick effects.

- The film was likely hand-colored in some releases, as was common with early films to enhance their visual appeal.

- This type of film was extremely popular with early cinema audiences who were amazed by the seemingly magical possibilities of the new medium.

- The complete woman created in the film was played by an actress who had to hold perfectly still between each photographed frame to create the illusion of gradual assembly.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of 'Artistic Creation' are scarce due to the limited film criticism of the era, but trade publications of the time praised Booth's ingenuity and the film's clever execution. The film was noted for its technical sophistication and was considered a prime example of British innovation in the emerging medium of cinema. Modern film historians recognize it as a significant early work in the development of special effects and animation techniques. The British Film Institute includes it among important early British films for its technical achievements and historical significance.

What Audiences Thought

Early cinema audiences were reportedly astonished by 'Artistic Creation' and similar trick films. The magical transformation effects were particularly impressive to viewers who had never seen such visual illusions before. The film was popular in music hall programs where it served as a highlight act. Contemporary audiences appreciated the humor and wonder of seeing drawings come to life, and the film's brevity made it ideal for the short attention spans typical of variety show audiences. The film's success helped establish the popularity of trick films in early cinema programming.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès' trick films

- Stage magic and illusion shows

- Victorian spiritualism

- Early animation experiments

- Theatrical special effects

This Film Influenced

- Early Disney animation

- Willis O'Brien's stop-motion work

- Ray Harryhausen's creature effects

- Modern CGI transformation scenes

- Music videos featuring animated elements

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the British Film Institute National Archive and has been digitally restored. It is also held in other film archives including the Library of Congress. The restoration has allowed modern audiences to appreciate the technical innovations of this early cinema masterpiece. The film survives in good condition considering its age, though some deterioration is visible in existing prints.