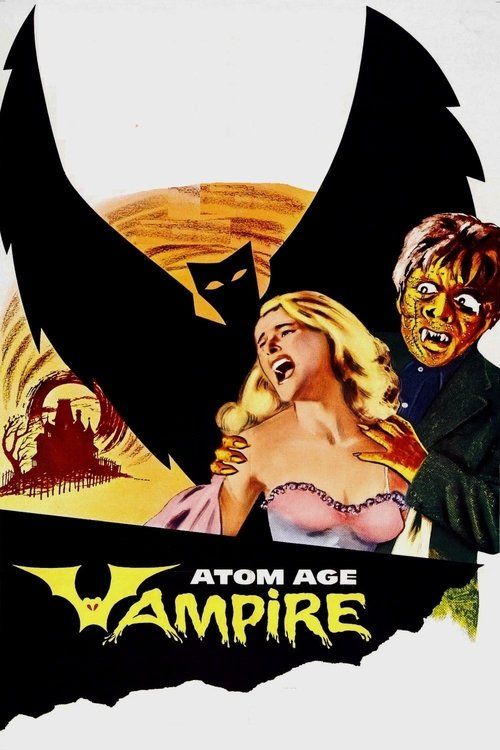

Atom Age Vampire

"Terror in the Test Tube! A New Dimension in Horror!"

Plot

When beautiful nightclub singer Jeanette Moreneau is horribly disfigured in a tragic car accident, her life seems ruined until she meets Professor Alberto Levin, a brilliant but obsessed scientist who has developed a revolutionary serum derived from glandular extracts that can restore damaged tissue. Levin successfully uses his treatment to restore Jeanette's beauty, but during the process he falls deeply in love with her, becoming possessive and jealous when she rekindles her romance with her former boyfriend Pierre. When the serum's effects begin to wear off and Jeanette's disfigurement starts to return, Levin realizes he must continually murder young women to harvest the glands needed to maintain her beauty. As the police investigate the string of brutal murders and Jeanette grows increasingly suspicious of Levin's activities, the scientist's obsession drives him to increasingly desperate measures, ultimately transforming him into a monstrous creature as he struggles to keep Jeanette beautiful at any cost.

About the Production

The film was shot in black and white with some sequences tinted for effect. The makeup effects for the disfigurement scenes were considered quite graphic for the time period. Production faced challenges with Italian censorship boards due to the horror elements and implied violence.

Historical Background

Atom Age Vampire emerged during a pivotal period in Italian cinema history, as the country was experiencing an economic boom and its film industry was expanding internationally. The early 1960s saw the rise of Italian horror cinema, following the breakthrough success of Mario Bava's 'Black Sunday' in 1960, which proved that Italian horror films could compete internationally. This film was part of that first wave, capitalizing on both the horror boom and contemporary anxieties about atomic science and radiation. The Cold War era's fascination and fear with atomic energy influenced many horror films of this period, with 'Atom Age' being a popular marketing term. The film also reflected changing social attitudes in Italy regarding beauty standards and the growing influence of American culture on European cinema. Its production coincided with the golden age of Italian genre filmmaking, which would soon give birth to the giallo and spaghetti western genres.

Why This Film Matters

Atom Age Vampire represents an important transitional work in Italian horror cinema, bridging the gap between classic Gothic horror and the more graphic, contemporary horror that would dominate the genre in the following decade. The film's focus on scientific horror rather than supernatural elements anticipated the 'mad scientist' subgenre that would become popular in 1960s horror cinema. Its commercial success in international markets helped demonstrate the viability of Italian horror productions for export, encouraging more investment in the genre. The film also exemplifies the practice of European horror films being retitled and re-edited for American distribution, a practice that would continue throughout the decade. While not as influential as some contemporaries, it contributed to the establishment of horror as a commercially viable genre in Italian cinema, paving the way for the explosion of Italian horror and giallo films in the mid-to-late 1960s.

Making Of

The production faced significant challenges with Italian censorship, which was particularly strict regarding horror content in the early 1960s. The filmmakers had to submit multiple cuts before receiving approval for theatrical release. The makeup effects, while crude by modern standards, were considered quite shocking for contemporary audiences and required extensive testing to achieve the desired level of grotesque disfigurement. Director Majano, coming from a background in serious drama, reportedly struggled with the horror elements and focused more on the psychological aspects of obsession and unrequited love. The film was shot quickly on a modest budget at Titanus Studios in Rome, with many scenes filmed at night to accommodate the limited production schedule. The American version was significantly re-edited by AIP (American International Pictures), who added new footage and changed character names to make it more accessible to US audiences.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Mario Montuori, utilizes stark black and white contrast to create a Gothic atmosphere reminiscent of classic horror films while maintaining a contemporary feel. The film employs dramatic lighting techniques, particularly in the laboratory scenes where shadows and harsh lighting emphasize the scientific horror elements. Camera work is generally straightforward but effective, with several tracking shots during the murder sequences that build tension. The disfigurement scenes use close-up photography to maximize the shock value of the makeup effects. The film's visual style bridges classic horror cinematography with more modern techniques, creating a distinctive look that reflects its transitional place in horror cinema history.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical terms, the film achieved notable effectiveness in its makeup effects for the disfigurement scenes, which were considered quite graphic for 1960. The transformation sequences used practical effects and makeup techniques that, while crude by modern standards, were effective in shocking contemporary audiences. The film's laboratory sets featured elaborate equipment that helped establish the scientific horror atmosphere. The cinematography's use of shadow and light created effective mood despite budget limitations. The film's sound design, particularly in the murder sequences, used audio techniques to enhance the horror elements without relying on excessive gore.

Music

The musical score was composed by Carlo Innocenzi, who created a dramatic orchestral soundtrack that emphasized the film's horror elements while incorporating romantic themes for the love story aspects. The music uses traditional horror film conventions with dissonant strings and brass stingers during tense moments, but also features more melodic passages during the romantic scenes. The soundtrack effectively enhances the film's atmosphere, particularly in the laboratory sequences where the music builds tension. The score has been noted by film music historians as an effective example of early 1960s European horror film composition, balancing traditional horror elements with more contemporary musical approaches.

Famous Quotes

Beauty is a terrible power when it's taken away from you.

I would kill for you, Jeanette. I would do anything to keep you beautiful.

Science is a weapon, and in the wrong hands, it can become the most terrible of all.

Every face has a price, and I'm willing to pay it.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening car accident sequence where Jeanette is disfigured, using effective makeup and editing to convey the horror of the moment.

- The first transformation scene where Levin's serum begins to fail, with Jeanette's face gradually reverting to its disfigured state.

- The laboratory sequence where Levin prepares his serum, with elaborate equipment and dramatic lighting creating a mad scientist atmosphere.

- The final confrontation between Levin and Jeanette, where the full extent of his obsession and transformation is revealed.

Did You Know?

- The film's original Italian title was 'Seddok, l'erede di Satana' (Seddok, Heir of Satan), but American distributors retitled it 'Atom Age Vampire' to capitalize on the atomic age horror trend.

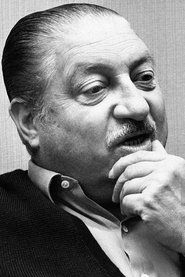

- Director Anton Giulio Majano was primarily known for dramatic films and TV productions, making this horror film an unusual entry in his filmography.

- The film's 'vampire' element is misleading - the scientist doesn't drink blood but rather harvests glands from his victims, making it more of a scientific horror film.

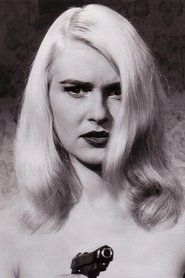

- Susanne Loret was a former Miss Italy contestant who transitioned to acting, with this being one of her most prominent film roles.

- The American version removed approximately 15 minutes of footage and added new scenes with different actors to make it more palatable for US audiences.

- The film was part of a wave of Italian horror films in the early 1960s that followed the international success of films like 'Black Sunday' (1960).

- The special effects makeup for the disfigurement scenes was created by Italian makeup artist Giannetto De Rossi, who would later work on many classic horror films.

- The film was released in different markets under various titles including 'Seddok' and 'The Vampire and the Ballerina' in some regions.

- Despite the title, there are no actual vampires in the film - the 'vampire' metaphor refers to the scientist's parasitic need to kill women to sustain Jeanette's beauty.

- The film's poster art in the US emphasized the monster aspect far more than the actual film content, creating misleading expectations for audiences.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was mixed to negative, with many reviewers dismissing the film as exploitative and derivative. Italian critics were particularly harsh, viewing it as a commercial departure from more artistic cinema. American reviews focused on the film's shock value, with Variety noting its 'effective moments of horror' but criticizing its 'ludicrous plot.' Modern reassessments have been more charitable, with horror historians recognizing the film as an interesting example of early Italian horror and noting its atmospheric qualities and effective use of black and white cinematography. The film is now appreciated by cult film enthusiasts for its place in horror history and its representation of early 1960s European horror aesthetics.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception was generally positive among horror fans, particularly in drive-in theaters where it found its primary American audience. The film's sensational title and lurid poster art attracted teenagers and horror enthusiasts looking for shock entertainment. Italian audiences responded moderately well, though it didn't achieve the same level of success as some contemporary horror productions. Over time, the film has developed a cult following among vintage horror enthusiasts, with many appreciating its place in horror history and its distinctive early 1960s aesthetic. The film's reputation has grown in cult film circles, where it's often discussed alongside other Italian horror classics of the era.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Frankestein (1931)

- Eyes Without a Face (1960)

- The Fly (1958)

- Black Sunday (1960)

This Film Influenced

- The Awful Dr. Orlof (1962)

- The Man Who Could Cheat Death (1959)

- The Vampire Lovers (1970)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in various formats including 35mm prints and digital transfers. The original Italian version has been preserved by Italian film archives, while the American version exists in the AIP collection. Multiple home video releases have been produced, with some restoration work done for DVD and Blu-ray releases by specialty labels like Severin Films and MVD Entertainment Group. The film is not considered at risk of being lost, though some differences between versions remain of interest to preservationists.