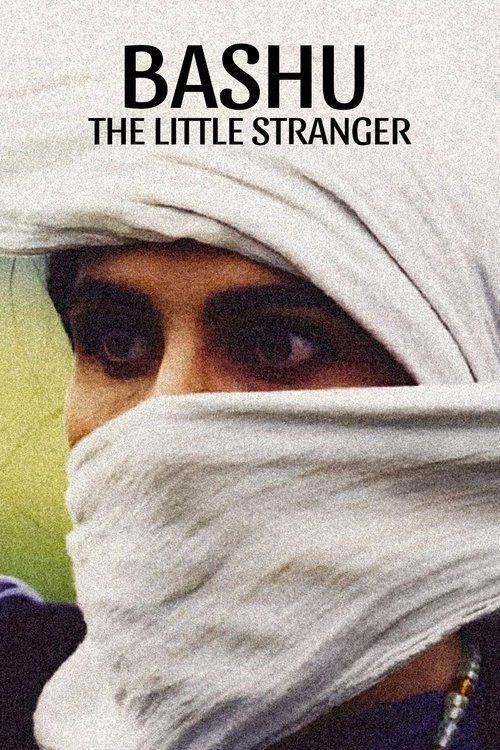

Bashu, the Little Stranger

"In the darkness of war, a child's light found a home"

Plot

During the Iran-Iraq War, 10-year-old Bashu witnesses his entire family and village destroyed by Iraqi bombing. Terrified and alone, he stows away in a truck that carries him far north to the lush, green region of Gilan, where the landscape, climate, and language are completely foreign to him. He encounters Naii, a resilient young mother struggling to maintain her farm while raising two children and waiting for her husband to return from the war front. Despite their inability to communicate verbally due to language barriers (Bashu speaks Arabic/Kurdish while Naii speaks Gilaki/Persian), they develop a profound bond through shared humanity, with Naii eventually adopting Bashu as her own child. The film explores their journey of mutual understanding and healing as Bashu gradually processes his trauma while adapting to his new life, culminating in a powerful testament to the resilience of the human spirit amid the devastation of war.

About the Production

Filmed during the final years of the Iran-Iraq War, the production faced numerous challenges including security concerns, limited resources, and government censorship. Director Bahram Beyzai had to navigate strict cultural regulations while depicting the realities of war. The film was shot in black and white for artistic reasons and to emphasize the stark contrast between war and peace. Child actor Adnan Afravian was discovered in a refugee camp, bringing authentic experience to his role. The filming in Gilan province required special permissions due to the sensitive border regions.

Historical Background

'Bashu, the Little Stranger' was created during one of the most tumultuous periods in modern Iranian history - the final years of the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) and the immediate aftermath of the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The film emerged from a cinematic landscape that had been radically transformed by the revolution, with strict new censorship codes and ideological requirements imposed on filmmakers. Despite these constraints, or perhaps because of them, the 1980s became known as a golden age for Iranian cinema, with directors finding creative ways to tell meaningful stories within the new parameters. The Iran-Iraq War had devastated southern Iran, particularly Khuzestan province where Bashu's character originates, creating millions of internal refugees and profound social trauma. Beyzai's film was revolutionary in its humanistic approach to depicting war's impact on civilians, particularly children, at a time when most Iranian war films focused on heroism and martyrdom. The north-south cultural divide depicted in the film reflects real regional tensions within Iran, while the story of displacement resonated with millions of Iranians who had been forced from their homes during the war.

Why This Film Matters

'Bashu, the Little Stranger' is widely regarded as a masterpiece of Iranian cinema and one of the most important films of the 20th century. It broke new ground in Iranian filmmaking by addressing themes of racism, regional prejudice, and cultural diversity within Iran - topics that had rarely been explored so directly in post-revolution cinema. The film's portrayal of a dark-skinned southern child finding refuge with a light-skinned northern family challenged prevailing social norms and sparked important conversations about Iranian identity. Internationally, the film helped establish Iranian cinema on the global stage, paving the way for the wave of Iranian films that would achieve critical acclaim in the 1990s and 2000s. Its success at major film festivals demonstrated that Iranian filmmakers could create universally resonant stories while maintaining their cultural authenticity. The film influenced a generation of Iranian filmmakers, including Abbas Kiarostami and Majid Majidi, who would later achieve international recognition. Within Iran, despite initial censorship, the film became a cultural touchstone, referenced in literature, academic discourse, and popular culture. Its humanistic message transcended political boundaries, making it one of the few Iranian films of its era to be appreciated both domestically and internationally without controversy.

Making Of

The making of 'Bashu, the Little Stranger' was fraught with challenges typical of Iranian cinema in the post-revolution era. Director Bahram Beyzai fought for years to get approval for the project, as authorities were initially reluctant to approve a film depicting the harsh realities of war from a child's perspective. The casting process was particularly challenging - Beyzai searched for months to find the perfect child actor to play Bashu, eventually discovering Adnan Afravian in a refugee camp. The film was shot on location in Gilan province during actual wartime conditions, with the cast and crew often working under threat of air raids. Susan Taslimi's performance as Naii was particularly demanding, as she had to convey complex emotions while speaking in the Gilaki dialect, which was not her native language. The film's use of multiple languages created additional challenges during post-production, requiring careful subtitle work for international releases. Despite these obstacles, or perhaps because of them, the film achieved a remarkable authenticity that resonated with audiences worldwide.

Visual Style

The film's black and white cinematography, executed by Mahmoud Kalari, is considered one of its most distinctive and powerful elements. Kalari's visual approach creates a stark contrast between the devastated, sun-scorched landscapes of southern Iran and the lush, misty environment of the northern Gilan region. The camera work employs long, contemplative takes that allow the natural performances to unfold organically, particularly in scenes between Bashu and Naii where visual communication replaces dialogue. Kalari uses natural lighting extensively, creating authentic textures that enhance the film's realism. The cinematography often employs low angles when filming Bashu, emphasizing his vulnerability and smallness in a world of chaos. Several scenes feature symbolic visual motifs - the recurring image of Bashu's small hands, the contrast between desert and forest, and the visual isolation of characters within the frame. The decision to shoot in black and white, while partly practical, creates a timeless quality that elevates the film beyond its specific historical context. Kalari's work on this film influenced a generation of Iranian cinematographers and helped establish a distinctive visual language for Iranian art cinema.

Innovations

While 'Bashu, the Little Stranger' may not showcase flashy technical innovations, it achieves remarkable technical excellence within its resource constraints. The film's sound design is particularly noteworthy for its handling of multiple languages and dialects, creating authentic audio environments for each region. The production team developed innovative techniques for integrating actual war footage seamlessly with newly shot material, maintaining visual consistency despite different source materials. The makeup and costume departments achieved impressive results in depicting the physical toll of war and displacement on Bashu's character, using subtle but effective techniques to show his journey from trauma to healing. The film's editing, by Shahram Assadi, employs a rhythmic pace that mirrors the emotional journey of the characters, with longer takes during moments of connection and quicker cuts during sequences of chaos and displacement. The production overcame significant technical challenges in filming during wartime conditions, including power outages, security concerns, and limited access to professional equipment. The team's ability to maintain high technical standards despite these obstacles demonstrates the resourcefulness and creativity that characterized the best of Iranian cinema during this period.

Music

The film's score, composed by Ahmad Pejman, masterfully blends traditional Iranian musical elements with contemporary classical influences. Pejman incorporates regional folk melodies from both southern and northern Iran, reflecting the cultural journey of the protagonist. The soundtrack features prominent use of the ney (Persian flute) and tar (stringed instrument), creating an emotional undercurrent that guides viewers through Bashu's psychological journey. Particularly effective is the use of silence during key moments, emphasizing the communication barriers between characters and allowing the visual storytelling to take precedence. The music swells during moments of emotional connection between Bashu and Naii, creating a sonic bridge where verbal communication fails. Pejman also incorporates subtle sound design elements, including the distant sounds of war that occasionally intrude upon the peaceful northern setting, reminding viewers of the ever-present trauma that haunts Bashu. The soundtrack was released as a standalone album and remains one of the most celebrated film scores in Iranian cinema history. Its ability to convey complex emotions without relying on dialogue has made it a study subject for film music students worldwide.

Famous Quotes

Naii: 'Sometimes the heart understands what words cannot say.' (spoken while gesturing to Bashu)

Bashu: 'Home is where someone waits for you.' (in broken Persian, learned from Naii)

Naii: 'In this world, we are all strangers until someone makes us family.'

Village elder: 'The north may be green, but the south has the sun in its people's hearts.'

Naii: 'War takes everything, but it cannot take our ability to love.'

Bashu: 'I don't remember their faces anymore, only the sound of the bombs.' (describing his lost family)

Naii: 'A child's tears are the same color in every language.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the bombing of Bashu's village through a child's terrified perspective, using sound and fragmented visuals to convey chaos

- Bashu's arrival in the green northern landscape, his first experience of rain and trees, filmed with wide-angle lenses emphasizing his wonder and isolation

- The wordless communication scene where Naii teaches Bashu to milk a cow using only gestures, demonstrating their growing bond

- The nightmare sequence where Bashu relives the bombing, filmed in expressionistic style with rapid cuts and distorted sound

- The final scene where Bashu, now speaking fluent Gilaki dialect, helps Naii in the fields, showing his complete integration into the new family

- The scene where Naii defends Bashu against prejudiced villagers, delivering a powerful speech about universal humanity

- The moment when Bashu first calls Naii 'mother,' filmed in a tight close-up capturing both characters' emotional breakthrough

Did You Know?

- This was the first Iranian film to be screened in Iran after the revolution that depicted the Iran-Iraq War from a civilian perspective

- Director Bahram Beyzai had to wait three years for government approval to make the film

- The film was banned in Iran for several years after its initial release due to its portrayal of war's impact on civilians

- Child actor Adnan Afravian was actually a refugee from Khuzestan, the region where Bashu's character originates

- The film features multiple languages: Persian, Gilaki dialect, Arabic, and Kurdish, reflecting Iran's linguistic diversity

- Susan Taslimi, who played Naii, was actually married to director Bahram Beyzai during the filming

- The black and white cinematography was a deliberate artistic choice, not due to budget constraints

- The film was selected as Iran's official submission for the Academy Awards but was ultimately not nominated

- Many of the war scenes were filmed using actual footage from the Iran-Iraq War, carefully integrated with the narrative

- The title character's name 'Bashu' means 'seeker' in Kurdish, symbolizing his search for safety and belonging

What Critics Said

Upon its international debut at the Venice Film Festival, 'Bashu, the Little Stranger' received overwhelming critical acclaim. Western critics praised its poetic visual style, emotional depth, and universal themes. The New York Times called it 'a masterpiece of humanist cinema' while Variety described it as 'profoundly moving and technically brilliant.' French critic Jean-Michel Frodon wrote in Le Monde that the film 'transcends cultural boundaries to speak directly to the human heart.' Iranian critics, though initially constrained by political considerations, later recognized the film as a landmark achievement in national cinema. The film's black and white cinematography was particularly praised, with many critics comparing its visual poetry to the works of Italian neorealism. Over time, the film has been reassessed as one of the most important cinematic statements on war and childhood trauma, regularly appearing in critics' lists of the greatest films of all time. Contemporary film scholars have analyzed its innovative use of language barriers as a metaphor for communication beyond words, and its subversive commentary on Iranian society under the guise of a simple story.

What Audiences Thought

Despite limited commercial release and initial censorship in Iran, 'Bashu, the Little Stranger' developed a devoted following among audiences who managed to see it through special screenings and film festivals. International audiences responded emotionally to the story, with many viewers reporting profound emotional impact during festival screenings. The film's word-of-mouth reputation grew steadily, particularly in Europe where it became a cult favorite among art house cinema enthusiasts. In Iran, though banned from general release for several years, copies circulated through underground networks, and the film eventually achieved legendary status among cinephiles. The character of Bashu became particularly beloved, with many Iranian viewers identifying with his experience of displacement and search for belonging. The film's emotional climax and resolution reportedly moved audiences to tears at screenings worldwide. Over the decades, the film has maintained its emotional power, with new generations discovering it through film studies courses and retrospective screenings. Modern audiences continue to praise its timeless message of human connection transcending cultural and linguistic barriers.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Film, Fajr International Film Festival (Tehran, 1989)

- Best Director, Fajr International Film Festival (Bahram Beyzai, 1989)

- Best Actress, Fajr International Film Festival (Susan Taslimi, 1989)

- Best Screenplay, Fajr International Film Festival (Bahram Beyzai, 1989)

- Best Film, Locarno International Film Festival (Switzerland, 1990)

- Special Mention, Cannes Film Festival (Directors' Fortnight, 1990)

- Best Film, Nantes Three Continents Festival (France, 1990)

- UNESCO Award (for promoting cultural understanding, 1990)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Italian Neorealism (particularly De Sica's 'Bicycle Thieves')

- Iranian New Wave cinema of the 1970s

- Soviet war films focusing on civilian experiences

- Classical Persian literature themes of exile and return

- World cinema traditions of child protagonists in war settings

This Film Influenced

- Children of Heaven (1997) - Majid Majidi

- Kandahar (2001) - Mohsen Makhmalbaf

- Turtles Can Fly (2004) - Bahman Ghobadi

- A Separation (2011) - Asghar Farhadi

- The Salesman (2016) - Asghar Farhadi

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the Iranian National Film Archive and several international film institutions including the Cinémathèque Française and the British Film Institute. In 2015, the film underwent a complete digital restoration by The Criterion Collection in collaboration with the Farabi Cinema Foundation. The restoration process involved scanning the original 35mm negatives and conducting extensive color grading to preserve the intended black and white contrast. The restored version was screened at Cannes Classics in 2016 and has been released on Blu-ray with extensive bonus materials. The film is also preserved in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York and the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley. Despite initial censorship in Iran, the film is now recognized as part of the nation's cultural heritage and is regularly screened in retrospectives and film studies programs.