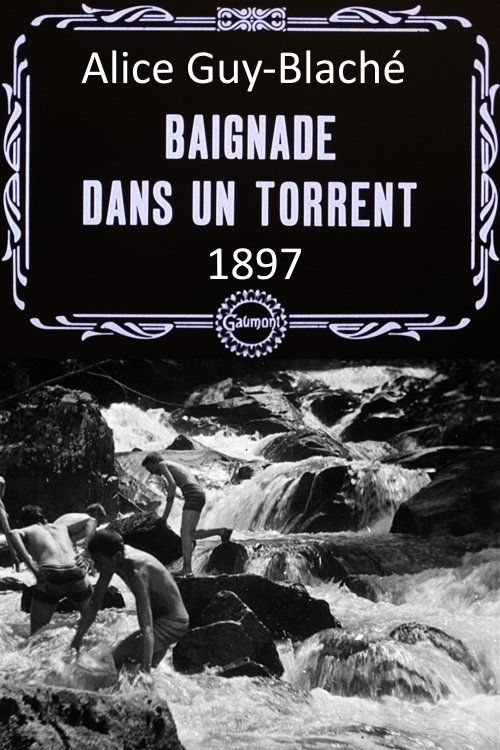

Bathing in a Stream

Plot

This short documentary film captures a group of children joyfully playing and bathing in a natural stream. The camera observes as the young boys and girls splash water at each other, run through the shallow water, and engage in innocent play typical of rural childhood. The film presents an unscripted, candid moment of everyday life, showcasing the simple pleasures of youth in nature. As one of Alice Guy-Blaché's early actualités, the film demonstrates her interest in capturing authentic human moments rather than staged performances. The children appear unaware of the camera, creating a naturalistic portrayal that was revolutionary for its time.

Director

About the Production

Filmed using a hand-cranked camera on 35mm film stock, this actualité required no artificial lighting as it was shot outdoors. The film represents Alice Guy-Blaché's early work during her tenure at Gaumont, where she was initially hired as a secretary but quickly became head of production. The short runtime was typical of films from this era, which were limited by technical constraints and audience attention spans. The children were likely local residents rather than professional actors, contributing to the film's authentic quality.

Historical Background

This film was created during the birth of cinema, just two years after the Lumière brothers' first public screening in 1895. 1897 was a pivotal year when film technology was rapidly evolving from scientific curiosity to commercial entertainment. The late 1890s saw the establishment of the first film production companies, including Gaumont, Pathé, and Biograph. This period marked the transition from single-shot actualités to more complex storytelling. Alice Guy-Blaché was working in a male-dominated field, yet she became one of cinema's most innovative early directors. The film also reflects the Belle Époque era in France, a time of relative peace, prosperity, and cultural flourishing before World War I. Early cinema often focused on scenes of everyday life, as filmmakers and audiences alike were fascinated by the ability to capture and replay moments from reality.

Why This Film Matters

Bathing in a Stream represents an important milestone in cinema history as one of the earliest films to document everyday life from a female perspective. Alice Guy-Blaché's work challenged the male-dominated early film industry and demonstrated that women could be creative visionaries behind the camera. The film exemplifies the actualité genre that dominated early cinema, showing how filmmakers were drawn to capturing authentic human experiences. This simple depiction of children at play also reveals early cinema's fascination with innocence and nature, themes that would recur throughout film history. The film's preservation of a moment from 1897 provides modern viewers with a window into late 19th-century childhood and rural life. Guy-Blaché's approach to filming, which emphasized natural behavior over staged performance, influenced the development of documentary filmmaking and realist cinema.

Making Of

Alice Guy-Blaché filmed this actualité during her pioneering years at Gaumont, where she revolutionized early cinema by moving beyond simple documentary footage to create narrative films. The production would have required transporting heavy camera equipment to an outdoor location, setting up the camera on a tripod, and manually cranking the film at a consistent speed. Guy-Blaché likely had to convince the children's parents to allow filming, as early cinema was still a novelty and many people were suspicious of the camera. The filming process was laborious, with each film reel containing only about one minute of footage. Guy-Blaché's ability to capture natural, unposed moments demonstrated her understanding of cinema's potential to document real life, a perspective that would influence her later narrative work.

Visual Style

The cinematography in Bathing in a Stream employs the fixed-camera perspective typical of early cinema, with the camera positioned to capture the entire scene without movement. The film was shot using natural sunlight, which creates bright, clear images but also results in the characteristic high contrast of early outdoor films. The composition follows the centered framing common to early actualités, ensuring all action remains within the frame. The depth of field captures both foreground and background elements, giving viewers a sense of the natural setting. The continuous single take creates a sense of real-time observation, emphasizing the documentary quality of the work. The camera work, while technically simple, demonstrates an understanding of how to frame action for maximum visibility and impact.

Innovations

While technically simple by modern standards, this film represents several important achievements for its time. The use of 35mm film stock was state-of-the-art in 1897, providing relatively high image quality. The successful outdoor filming demonstrated early cinematographers' ability to work with natural lighting conditions. The film's preservation of movement at 16-24 frames per second was a significant technical accomplishment. The capture of spontaneous action rather than staged performance showed an advancement in documentary filmmaking techniques. The film also represents Alice Guy-Blaché's early mastery of the medium, as she was able to produce technically competent footage while working with cumbersome equipment and limited resources.

Music

The film was originally silent, as synchronized sound technology would not be developed until the late 1920s. During initial screenings, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small ensemble playing popular tunes or classical pieces appropriate to the mood. The music would have been improvised or selected from existing repertoire, as original film scores were not yet common. Some venues might have used sound effects created by live performers to enhance the experience, such as water sounds. Modern screenings of the film often feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate music to recreate the early cinema experience.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue in this silent film

Memorable Scenes

- The opening shot showing children entering the stream with hesitation then joy, the central sequence of water play and splashing, the final moments as the children reluctantly leave the water, all captured in a single continuous take that preserves the authentic rhythm of childhood play

Did You Know?

- Alice Guy-Blaché is considered the first female film director and possibly the first person to create narrative fiction films

- This film was produced when Guy-Blaché was just 25 years old and head of production at Gaumont

- The film was shot using the Lumière brothers' Cinématographe technology, which was licensed by Gaumont

- Early actualités like this were often shown alongside magic lantern shows and live performances in music halls

- Guy-Blaché made over 700 films during her career, though many have been lost

- This film represents the genre of 'actualités' - early documentaries showing real-life scenes

- The children in the film would have been filmed without any payment or formal contracts, common practice in early cinema

- Gaumont was one of the world's first film companies, founded by Léon Gaumont in 1895

- The film was likely hand-colored frame by frame for special screenings, a common practice for important productions

- Alice Guy-Blaché's work was largely forgotten until feminist film historians rediscovered her contributions in the 1970s

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception for 1897 films was virtually non-existent as film criticism had not yet developed as a profession. Reviews, if any, appeared in general newspapers or trade publications focused on the novelty of moving pictures rather than artistic merit. Modern film historians and critics recognize Bathing in a Stream as an important example of early actualité filmmaking and Alice Guy-Blaché's pioneering work. The film is valued for its authentic depiction of 19th-century life and its role in documenting the early development of cinema. Contemporary scholars view it as evidence of Guy-Blaché's early talent and her understanding of cinema's potential to capture reality. The film is often cited in discussions about women's contributions to early cinema and the development of documentary film techniques.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1897 were fascinated by any moving image, and this film would have been received with wonder and excitement. The sight of moving, lifelike images on a screen was a magical experience for viewers who had never seen such technology. The familiar subject matter of children playing would have made the film particularly relatable and appealing to audiences of all ages. Early cinema programs typically consisted of multiple short films, so this actualité would have been part of a varied entertainment lineup. The film's outdoor setting and natural light would have provided clear, bright images that were impressive for the time. Modern audiences viewing the film in archives or museums often express fascination with the window into the past and the realization that these real children from 1897 are captured forever in motion.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Lumière brothers' actualités

- Early documentary photography

- Realist painting traditions

- Stage photography techniques

This Film Influenced

- Other Gaumont actualités

- Early documentary films

- Children in cinema genre

- Naturalist filmmaking movement

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of this specific Alice Guy-Blaché film is uncertain, as many of her early Gaumont works have been lost. Some of her films from this period survive in archives such as the Cinémathèque Française, the Library of Congress, and the British Film Institute. The film may exist as a paper print or nitrate copy in various film archives. Given its historical importance as one of Guy-Blaché's early works, efforts have likely been made to locate and preserve any existing copies. The film's survival would depend on whether Gaumont maintained copies or if it was distributed internationally where preservation efforts might have saved it.