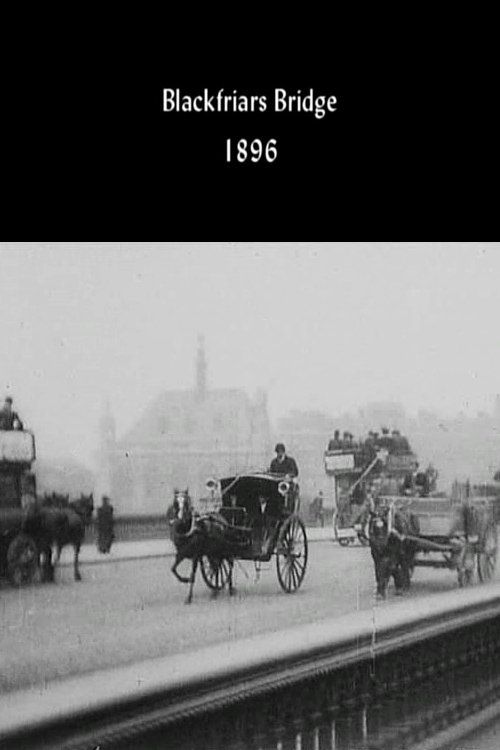

Blackfriars Bridge

Plot

This pioneering actuality film captures a typical day on Blackfriars Bridge in London during the Victorian era. The camera is positioned to record the steady flow of traffic crossing the iconic bridge, featuring elegantly dressed pedestrians in top hats and formal Victorian attire alongside horse-drawn carriages and carts. The film provides a mesmerizing window into 19th-century urban life, showcasing the bustling activity of one of London's most important river crossings. As one of the earliest examples of documentary filmmaking, it preserves a moment of everyday London life that would otherwise be lost to history. The simple yet effective composition demonstrates the emerging language of cinema, using a fixed camera position to create a sense of movement and life within the frame.

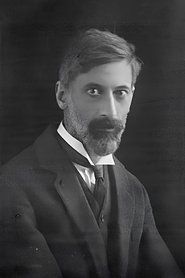

Director

About the Production

Filmed using Robert W. Paul's own camera invention, the Paul Animatograph. The camera was likely positioned on a tripod at a fixed vantage point to capture the bridge traffic. As with most films of this period, it was shot in a single continuous take with no editing. The film stock would have been 35mm celluloid, and the camera was hand-cranked, resulting in variable frame rates typically between 16-24 frames per second.

Historical Background

1896 was a pivotal year in cinema history, marking the transition from peep-show devices to projected motion pictures. The Lumière brothers had held their first public screening in Paris in December 1895, and cinema was rapidly spreading globally. In Britain, this period saw the emergence of native filmmakers like Robert W. Paul who competed with imported French films. Victorian London was the world's largest city, with a population of over 6 million people, and was experiencing rapid technological and social change. The bridge itself represented Victorian engineering prowess and the modernization of urban infrastructure. This film was created during the height of the British Empire, when London was the center of global commerce and culture. The year 1896 also saw the first films shown in the United States, the establishment of the first film production companies, and the beginning of cinema as a commercial entertainment medium.

Why This Film Matters

Blackfriars Bridge represents one of the earliest examples of documentary filmmaking and the 'actuality' genre that dominated early cinema. It demonstrates how filmmakers immediately recognized cinema's potential to capture and preserve reality. The film is historically significant as a visual record of Victorian London, showing transportation methods, fashion, and urban life that would soon disappear. It exemplifies the British contribution to early cinema development, particularly in documentary traditions. The film also illustrates the universal appeal of simple observational cinema, a format that would influence generations of documentary filmmakers. As part of the first wave of films showing recognizable locations, it helped establish cinema's ability to bring distant places to local audiences. The preservation of everyday scenes like this has proven invaluable to historians and researchers studying 19th-century urban life.

Making Of

Robert W. Paul entered filmmaking in 1894 when he was asked to duplicate Edison's Kinetoscope for the British market. After successfully creating his own version, Paul realized the limitations of peep-show devices and began developing projection systems. This led to the creation of his Animatograph camera and projector. Blackfriars Bridge was filmed during Paul's most productive period in 1896 when he was rapidly expanding his catalog of actuality films. The filming would have required setting up a bulky camera in a public space, which would have attracted curious onlookers unfamiliar with motion picture technology. Paul often employed a 'capture reality' approach, positioning his camera to document everyday scenes without interference or staging. The bridge location was strategically chosen as it offered both architectural interest and continuous movement of subjects.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Blackfriars Bridge is characteristic of early actuality films, employing a fixed camera position and a single continuous take. The camera was likely positioned at an elevated angle to capture both the bridge structure and the movement across it. This static approach was necessitated by the bulky and unwieldy nature of early film cameras. The composition creates a natural sense of depth as subjects move from foreground to background. The black and white imagery of the era creates stark contrasts that emphasize the silhouette effects of the bridge architecture and passing figures. The variable frame rate of hand-cranked cameras of this period would have created subtle variations in motion speed. The framing demonstrates an early understanding of visual balance, with the bridge's architectural elements providing a strong compositional structure.

Innovations

Blackfriars Bridge was filmed using Robert W. Paul's proprietary camera technology, which was significant as one of the first British-made motion picture cameras. Paul's cameras represented an important technical achievement in early cinema, as they were designed and built independently of American or French patents. The film demonstrates early mastery of exposure techniques for outdoor shooting, a significant challenge in the era of slow film stocks. The stability of the image indicates effective use of tripod mounting, which was still being refined for motion picture work. The film's survival through multiple generations of duplication speaks to the durability of early 35mm film stock. Paul's work on this and similar films contributed to the standardization of 35mm film as the industry format. The film also represents early experiments in capturing motion and determining appropriate frame rates for smooth reproduction.

Music

Originally, Blackfriars Bridge would have been screened as a silent film, as synchronized sound technology did not exist in 1896. During initial screenings, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small ensemble in music halls and theaters. The musical accompaniment would have been improvised or selected from popular pieces of the era, often light, upbeat melodies to complement the visual activity. Some venues might have used sound effects created by live performers to enhance the viewing experience. Modern screenings and restorations sometimes add period-appropriate musical scores to recreate the historical viewing experience. The absence of original recorded sound means that contemporary audiences experience the film as it was originally seen - as a purely visual medium enhanced by live performance.

Memorable Scenes

- The continuous flow of horse-drawn carriages and formally dressed pedestrians crossing the bridge, creating a living tapestry of Victorian London life that preserves a moment of urban history in motion

Did You Know?

- Robert W. Paul was originally an electrical engineer and instrument maker before entering the film business

- This film was part of Paul's early series of 'actuality' films documenting London life

- Blackfriars Bridge, opened in 1869, was one of the first bridges across the Thames in central London

- The film demonstrates the 'phantom ride' technique popular in early cinema, where the camera appears to move through space

- Paul's cameras were among the first manufactured in Britain, as he initially copied Edison's Kinetoscope

- The top hats and formal attire shown were typical daily wear for middle and upper-class Londoners of the 1890s

- Horse-drawn omnibuses like those shown in the film were the primary form of public transport in London before motor buses

- This film was likely screened as part of a variety program at music halls or early dedicated film venues

- Paul's film company was one of the most successful British production companies of the 1890s

- The film survives today through preservation efforts by film archives, notably the BFI National Archive

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of such early actuality films is largely undocumented, as film criticism as a discipline did not yet exist. However, these films were generally received with wonder and fascination by audiences who had never before seen moving images. Modern film historians and critics recognize Blackfriars Bridge as an important example of early documentary practice. Scholars value it for its unmediated view of Victorian London and its role in establishing documentary conventions. The film is often cited in academic studies of early cinema, British film history, and the development of documentary form. Critics note its compositional simplicity and effectiveness in capturing the rhythm of urban life. The film is appreciated for what it represents - the birth of cinema's documentary impulse and the medium's inherent ability to preserve time.

What Audiences Thought

Victorian audiences reportedly found these actuality films mesmerizing and magical. The sight of familiar locations and everyday scenes brought to life through motion pictures created a sense of wonder and novelty. Blackfriars Bridge would have been particularly engaging for London audiences who recognized the location and could see themselves and their city represented in this new medium. The film's appeal lay in its combination of the familiar (a known London landmark) with the revolutionary (moving images). These early actuality films were often shown multiple times to satisfy audience demand, as viewers would notice new details with each viewing. The simple, direct nature of the film made it accessible to all social classes, contributing to cinema's early mass appeal.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Edison's Kinetoscope films

- Lumière brothers' actuality films

- Eadweard Muybridge's motion studies

- Early photographic documentation

- Victorian observational traditions

This Film Influenced

- Paul's subsequent London actuality films

- Early British documentary tradition

- City symphony films of the 1920s

- British Transport Films

- Modern urban documentary cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives and has been preserved by film archives, notably the British Film Institute (BFI) National Archive. Digital restorations have been made from surviving 35mm prints. The film is considered to be in good preservation condition for its age, though some degradation is typical of films from this period. Multiple versions exist in various archives worldwide, reflecting the international distribution of Paul's films. The preservation status represents a success story in early film conservation, as many films from this era have been lost completely.