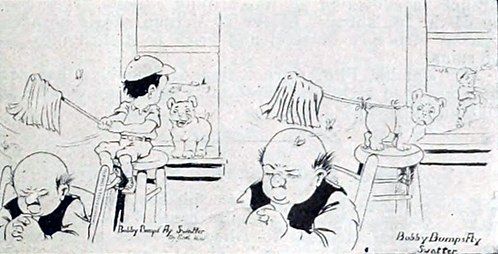

Bobby Bumps' Fly Swatter

Plot

In this early animated short, young Bobby Bumps and his faithful puppy find themselves in a series of comedic misadventures centered around a fly swatter. When Bobby attempts to deal with a pesky housefly, his efforts quickly spiral into chaos as his puppy interferes at every turn. The simple premise escalates into elaborate slapstick sequences as the fly swatter becomes a prop for increasingly disastrous situations. Bobby's frustration grows as the fly continues to evade capture while his well-meaning but clumsy dog creates more havoc than help. The film culminates in a chaotic finale where both boy and dog learn that sometimes the simplest problems can create the biggest messes.

Director

Earl HurdAbout the Production

This film was created using the cel animation technique pioneered by Earl Hurd, which involved drawing characters on transparent celluloid sheets and photographing them over static backgrounds. The Bobby Bumps series was one of the first successful animated series to utilize this revolutionary method, significantly streamlining the animation process. Hurd's collaboration with J.R. Bray established one of the first professional animation studios in America.

Historical Background

1916 was a pivotal year in early animation history, occurring during World War I when the film industry was rapidly evolving. The United States was still neutral in the war, and American cinema was experiencing a golden age of innovation. Animation was transitioning from simple trick films and novelty acts to legitimate narrative entertainment. The Bobby Bumps series emerged during this transformation period, helping establish animation as a commercially viable medium. The film industry was centered in New York at this time, with Hollywood still in its infancy. This era saw the birth of many animation techniques and conventions that would define the medium for decades to come.

Why This Film Matters

Bobby Bumps' Fly Swatter represents an important milestone in the development of American animation as an art form and industry. The series helped establish the template for animated shorts featuring relatable child characters in everyday situations. The boy-and-dog dynamic would become a staple in animation for generations, influencing everything from Tom and Jerry to modern animated series. The film's use of cel animation technology set the standard for the entire animation industry, making production more efficient and allowing for greater artistic expression. These early shorts also reflected American values and humor of the 1910s, capturing the innocence and mischief of childhood in a rapidly modernizing society.

Making Of

Earl Hurd created Bobby Bumps as a continuation of his earlier character 'Dudley Do-Right' (not to be confused with the later Jay Ward character). The animation was produced in Hurd's home studio before he partnered with J.R. Bray. Each frame was hand-drawn on paper, then transferred to cels for coloring. The sound was originally provided by live musicians in theaters, with suggested musical cues included in the film's distribution materials. Hurd often drew inspiration from his own childhood experiences and the mischief he and his friends would get into. The production team was small, often consisting of just Hurd, an assistant, and a camera operator, making these shorts remarkable achievements for their time.

Visual Style

The animation utilized the innovative cel technique developed by Hurd, allowing for smoother movement and more detailed backgrounds than previous methods. The visual style featured bold, clear lines and simple but expressive character designs typical of the period. Camera work was straightforward, focusing on clear presentation of the action without complex angles. The animation emphasized fluid character movement and exaggerated physical comedy, with particular attention to the contrast between Bobby's frustrated expressions and the dog's playful antics.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was its use of cel animation, which Hurd co-patented and which revolutionized the animation industry. This technique allowed animators to separate moving elements from static backgrounds, dramatically reducing production time and costs. The series also demonstrated early use of character consistency across multiple films, establishing the concept of recurring animated characters. The animation showed sophisticated understanding of timing and movement for the period, with smooth character motion and effective comedic pacing.

Music

As a silent film, the original score would have been provided by live theater musicians. Distribution materials included suggested musical cues and themes for different scenes. The music would typically have been light and comedic, using popular songs of the era and classical pieces adapted for the action. The fly swatter scenes would have been accompanied by playful, staccato music to enhance the comedic timing. The absence of dialogue meant the visual storytelling and music had to carry the entire narrative weight.

Memorable Scenes

- The escalating sequence where Bobby attempts to swat the fly while his puppy continuously interferes, resulting in increasingly elaborate slapstick chaos that culminates in both boy and dog becoming entangled in a mess of household items

Did You Know?

- Earl Hurd co-patented the cel animation process in 1914, which became the standard technique for animation for decades

- The Bobby Bumps series was one of the first recurring animated characters in film history

- Bobby Bumps was often accompanied by his dog Fido, making them one of the first animated boy-and-dog duos

- This was one of over 30 Bobby Bumps shorts produced between 1915 and 1925

- The series was notable for its use of speech balloons in some films, an innovation for the time

- Bray Productions was the first animation studio to use assembly-line production methods

- Hurd's work on Bobby Bumps helped establish many animation conventions still used today

- The fly swatter theme was a common trope in early comedy shorts, representing the eternal struggle against pesky problems

- These films were typically shown as part of vaudeville programs or before feature presentations

- The Bobby Bumps character was inspired by the 'rascal' archetype popular in early 20th century American culture

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade publications like Variety and Moving Picture World praised the Bobby Bumps series for its technical innovation and wholesome entertainment value. Critics noted the superior animation quality compared to earlier shorts and appreciated the character-driven humor. Modern film historians recognize the series as groundbreaking for its time, with animation scholars citing Hurd's work as crucial to the development of the medium. The films are studied today for their historical importance and as examples of early American animation techniques.

What Audiences Thought

The Bobby Bumps shorts were popular with audiences of their time, particularly children and families. The simple, visual humor translated well across language barriers, making the series popular internationally. Theater owners reported positive responses from patrons, and the series became a reliable part of their programming. The character of Bobby Bumps resonated with audiences as a relatable, mischievous child whose adventures they could enjoy vicariously. The series maintained popularity throughout its run, spawning merchandise and comic strip adaptations.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier trick films by Georges Méliès

- Winsor McCay's Gertie the Dinosaur

- Comic strip humor of the period

- Vaudeville comedy routines

- Chaplin's slapstick style

This Film Influenced

- Later Bobby Bumps shorts

- Felix the Cat cartoons

- Mickey Mouse shorts

- Tom and Jerry series

- Looney Tunes shorts

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in various archives and collections, including the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Some copies have been restored and digitized as part of early animation preservation projects. While not considered lost, many original nitrate prints have deteriorated over time, making preservation efforts crucial for maintaining this piece of animation history.