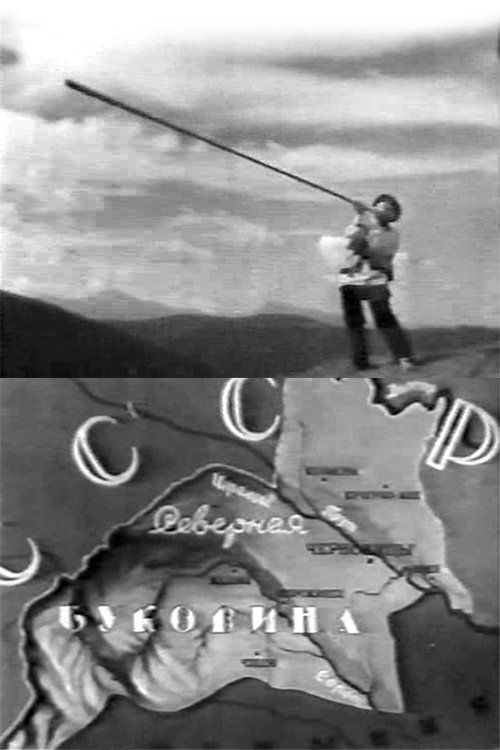

Bukovyna, Ukrainian Land

Plot

This 1940 documentary chronicles the Soviet annexation of Northern Bukovina from Romania, presenting it as the joyful reunification of Ukrainian lands with their motherland. The film captures the transition of power through carefully staged scenes of peasants welcoming Soviet troops, celebrating their supposed liberation from Romanian oppression. Dovzhenko documents the region's natural beauty, agricultural resources, and cultural life while emphasizing the historical ties between Bukovina and the rest of Ukraine. The narrative follows the immediate changes brought by Soviet rule, including land redistribution and the establishment of collective farms. The documentary serves as both a historical record and political propaganda, showcasing the supposed benefits of Soviet citizenship for the Bukovinian people.

Director

About the Production

Filmed immediately after the Soviet annexation of Northern Bukovina in June 1940, the documentary was rapidly produced to capture and legitimize the political transition. Dovzhenko and Solntseva worked with a small crew to document both authentic scenes and staged celebrations. The production faced challenges due to the recent political upheaval and the need to quickly establish Soviet administrative control in the region. The filmmakers had to navigate complex political sensitivities while creating a compelling narrative about the reunification of Ukrainian lands.

Historical Background

The film was produced in the immediate aftermath of the Soviet Union's annexation of Northern Bukovina from Romania in June 1940, following the Soviet-German Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. This territorial transfer was part of a broader Soviet expansion into Eastern Europe that also included the Baltic states and parts of Poland and Finland. The documentary served as part of a massive propaganda campaign to legitimize these acquisitions both domestically and internationally. The timing was particularly significant as Europe was already at war, and the Soviet Union was positioning itself as a protector of Slavic peoples. The film reflected Stalin's policy of 'reunifying' Ukrainian lands that had been separated from the Ukrainian SSR after the Russian Revolution and Civil War.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the few documentary records of the 1940 Soviet annexation of Bukovina, the film has immense historical value despite its propagandistic nature. It represents a crucial moment in Ukrainian cinema history, showcasing how even a master filmmaker like Dovzhenko had to adapt his artistic vision to serve Soviet political needs. The documentary contributed to the Soviet narrative of Ukrainian territorial unity while simultaneously erasing the complex multi-ethnic reality of Bukovina, which had significant Romanian, Jewish, and German populations alongside Ukrainians. The film remains an important artifact for understanding Soviet propaganda techniques and the cultural politics of territorial expansion.

Making Of

The production of 'Bukovyna, Ukrainian Land' was rushed through in the summer and fall of 1940, as the Soviet authorities wanted to quickly create visual justification for their territorial acquisition. Dovzhenko, who had previously faced criticism for his poetic style, was under pressure to produce more straightforward propaganda. He and Solntseva traveled with a small crew to the newly annexed region, where they filmed both genuine reactions to the Soviet takeover and carefully choreographed scenes of celebration. The filmmakers worked closely with local Soviet officials to identify 'appropriate' subjects and locations. Dovzhenko struggled with the assignment, as his artistic sensibilities often conflicted with the demands of political propaganda. Despite these constraints, he managed to infuse the documentary with his characteristic visual poetry, particularly in scenes depicting the region's natural landscapes and rural life.

Visual Style

The documentary showcases Dovzhenko's masterful use of landscape photography, with sweeping shots of the Carpathian foothills and fertile plains of Bukovina. The cinematography combines documentary realism with carefully composed tableaux vivants that celebrate rural life and Soviet progress. Dovzhenko employs his characteristic use of natural light, particularly in outdoor scenes of peasants working the fields. The camera work includes both wide establishing shots of the region's geography and intimate close-ups of human faces during staged celebrations. The visual style balances the requirements of propaganda with moments of pure cinematic poetry, particularly in sequences showing the natural beauty of the Bukovinian countryside.

Innovations

The film utilized portable sound recording equipment that allowed for on-location synchronization of image and sound, still relatively advanced for Soviet documentary production in 1940. Dovzhenko employed innovative camera techniques including aerial shots of the Bukovinian landscape, achieved through early use of camera mounts on aircraft. The production overcame significant technical challenges related to the rapid deployment of film equipment to the newly annexed region and the establishment of processing facilities. The documentary demonstrated advances in location sound recording under difficult field conditions. The film's preservation and reconstruction after World War II damage also represented significant technical achievement in Soviet film restoration.

Music

The film features a musical score composed by Ukrainian composer Borys Lyatoshynsky, incorporating folk melodies from the Bukovina region with Soviet patriotic themes. The soundtrack includes both diegetic sounds of rural life and non-diegetic orchestral music that emphasizes the emotional and political content of each scene. Traditional Ukrainian folk songs are prominently featured, particularly in sequences showing cultural celebrations. The musical arrangements were designed to reinforce the narrative of Ukrainian cultural unity while also celebrating Soviet achievement. The sound design includes voice-over narration that provides historical context and political interpretation of the visual material.

Famous Quotes

From the Carpathians to the Dnipro, Ukrainian lands are united once more under Soviet rule

The peasants of Bukovina welcome their liberators with bread and salt

Under Romanian oppression, our brothers suffered. Under Soviet power, they thrive

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the natural beauty of Bukovina's mountains and valleys

- Staged celebrations of peasants greeting Soviet troops with traditional Ukrainian bread and salt

- Scenes of land redistribution documents being signed by grateful peasants

- Montage comparing Romanian rule with Soviet administration

- Final sequence showing collective farm workers celebrating their new Soviet citizenship

Did You Know?

- This was one of the last films Dovzhenko completed before being denounced during Stalin's purges of Ukrainian intellectuals

- The documentary was made just months after the Soviet Union annexed Northern Bukovina from Romania under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

- Dovzhenko had personal connections to the region, as his family had roots in nearby areas of Western Ukraine

- The film was shot on location during the actual transition period, making it a unique historical document of the annexation

- Many scenes were staged or re-enacted for the camera, a common practice in Soviet documentary filmmaking of the era

- The original film negative was partially damaged during World War II and had to be reconstructed in the 1950s

- Yuliya Solntseva, Dovzhenko's wife and collaborator, served as co-director and handled much of the on-location filming

- The documentary was shown to Soviet officials to demonstrate the successful integration of the new territories

- Despite its propaganda purpose, the film contains valuable ethnographic material about Bukovinian culture and traditions

- The film was banned in Romania and other Western countries during the Cold War due to its political content

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its clear political message and effective portrayal of the 'joyful reunification' of Ukrainian lands. Official reviews in Pravda and Izvestia highlighted Dovzhenko's successful transformation into a creator of socialist realist cinema. However, some Ukrainian intellectuals privately expressed disappointment at what they saw as the compromise of Dovzhenko's artistic integrity. Western critics had limited access to the film during the Cold War, but those who saw it dismissed it as typical Soviet propaganda. Modern film historians recognize the documentary as a complex work that balances political necessity with moments of visual poetry characteristic of Dovzhenko's style.

What Audiences Thought

Within the Soviet Union, the film was shown in workers' clubs, collective farms, and educational institutions as part of political education about the new territories. Audiences in Ukraine generally received it positively, as it aligned with widespread desire for the unification of Ukrainian lands. In the newly annexed Bukovina region, screenings were organized to help legitimize Soviet rule, though genuine public reactions varied. The film was not commercially released in the traditional sense, as it was distributed through state channels rather than theaters. After World War II, the documentary continued to be used in Soviet schools and party meetings to teach about the 'reunification' of Ukrainian territories.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, 2nd class (1941)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet socialist realism

- Vertov's documentary theory

- Dovzhenko's earlier poetic films

- Soviet propaganda cinema tradition

- Ukrainian folk culture

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet documentaries about territorial acquisitions

- Post-war Ukrainian documentary tradition

- Soviet films about 'reunified' territories

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved in the Gosfilmofond of Russia and the Dovzhenko Film Studios archive in Ukraine. The original negative suffered damage during World War II but was reconstructed in the 1950s. A restored version was created in the 1970s for the Dovzhenko retrospective. The film is considered partially preserved with some scenes missing or damaged. Recent digital restoration efforts have been undertaken by Ukrainian film archives, though funding limitations have prevented complete restoration.