Children Digging for Clams

Plot

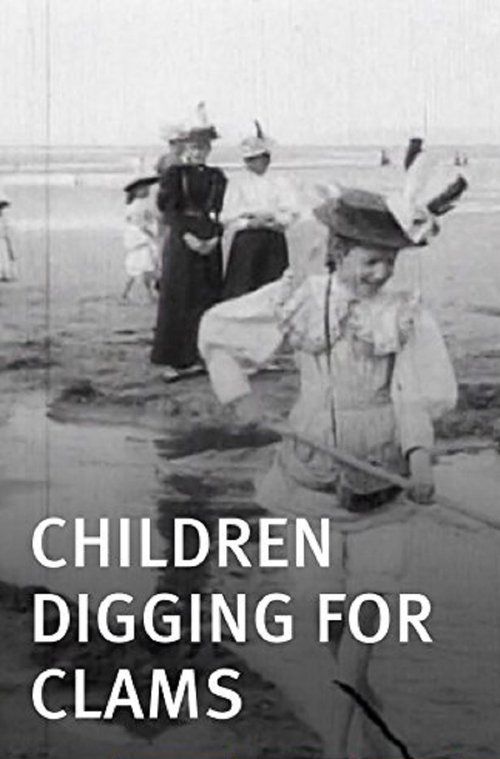

This early actuality film captures a group of children engaged in the humble activity of digging for clams along a shoreline. The young participants, dressed in period-appropriate attire, work diligently with small tools and their bare hands to unearth shellfish from the wet sand. The camera observes their collaborative efforts as they occasionally hold up their findings for examination. The simple yet profound documentation of this everyday scene represents one of cinema's earliest attempts to capture authentic human activity in its natural setting. The film concludes with the children continuing their labor, unaware of the historical significance of their being among the first subjects ever captured on motion picture film.

Director

About the Production

Filmed by Alexandre Promio, one of the Lumière brothers' most skilled cinematographers, using the Cinématographe device. The film was shot on location, likely during one of Promio's extensive travels for the Lumière company. The natural lighting and outdoor setting were typical of early Lumière productions, which favored actuality over staged scenes. The film was processed and developed using the Lumière brothers' proprietary techniques.

Historical Background

1896 was a pivotal year in cinema history, just one year after the Lumière brothers' first public screening in Paris. The art of motion pictures was in its infancy, and filmmakers were still discovering the possibilities and limitations of the medium. This period saw the proliferation of actuality films - short documentaries capturing scenes from everyday life - as filmmakers explored what could be captured on film. The industrial revolution had transformed society, and there was great fascination with documenting both traditional activities and modern life. France was at the center of cinematic innovation, with the Lumière company leading the way in both technical advancement and content creation. The film emerged during the Belle Époque, a period of cultural and artistic flourishing in France that encouraged experimentation with new forms of expression.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the earliest documentary films, 'Children Digging for Clams' represents the birth of non-fiction cinema and the documentary tradition that would follow. The film exemplifies the Lumière brothers' philosophy of capturing reality rather than creating staged spectacles, which contrasted with Georges Méliès' approach to fantastical cinema. This simple documentation of everyday activity established a precedent for ethnographic film and social documentary. The film also serves as an invaluable historical document, preserving a glimpse of late 19th-century coastal life and childhood activities. Its survival allows modern viewers to connect directly with the past in a way that photographs or written descriptions cannot match. The film represents the democratic potential of cinema to capture and preserve all aspects of human life, not just the spectacular or significant.

Making Of

Alexandre Promio, working as an operator for the Lumière brothers, would have transported the heavy Cinématographe equipment to the coastal location where this film was shot. The filming process required careful preparation as the camera had to be manually cranked at a consistent speed to capture smooth motion. The children featured were likely local residents who happened to be engaged in their daily activity when Promio arrived. The filmmaker would have had to set up his camera on a tripod and position himself at an optimal distance to capture the scene clearly. Early film shoots were public events, often attracting curious onlookers who had never seen motion picture equipment before. The entire filming process for this short actuality would have taken only a few minutes, but the preparation and travel time could have been substantial.

Visual Style

The film was shot using the Lumière Cinématographe, which used 35mm film with a perforation format developed by the Lumière brothers. The camera was stationary, mounted on a tripod, which was typical of early actuality films. The composition follows the conventions of the period, with a medium-wide shot that captures the entire scene and its participants. Natural lighting was used, as the film was shot outdoors, creating a soft, naturalistic quality to the image. The frame rate was likely 16-18 frames per second, standard for early Lumière productions. The black and white cinematography, while technically primitive by modern standards, was revolutionary for its time and capable of capturing remarkable detail.

Innovations

The film represents several technical achievements of early cinema. The use of the Cinématographe, which was lighter and more portable than competing devices like Edison's Kinetoscope, allowed for location filming of authentic scenes. The film demonstrates the Lumière brothers' advanced film processing techniques, which produced relatively clear and stable images for the period. The ability to capture motion smoothly with manual cranking was a significant technical accomplishment. The film's survival and preservation also testify to the durability of the celluloid medium and the effectiveness of early archival practices. The short runtime was technically necessary due to the limitations of early film cameras and projectors.

Music

As a silent film, 'Children Digging for Clams' had no synchronized soundtrack. During original screenings in 1896, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically performed on piano or by a small ensemble. The musical accompaniment was often improvised and might have included popular songs of the era or classical pieces appropriate to the mood of the scene. For a film depicting children at play, the music would likely have been light and cheerful. Modern screenings of the film may feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate music to enhance the viewing experience.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening shot reveals several children scattered along the shoreline, bent over with concentration as they dig into the wet sand with their hands and small tools. One child occasionally stands up to examine their findings, holding up a small clam for inspection before returning to work. The continuous, unedited capture of this simple activity creates a mesmerizing rhythm of labor and discovery that exemplifies early cinema's fascination with documenting authentic human behavior.

Did You Know?

- This film is part of the Lumière brothers' extensive catalog of actuality films that documented everyday life in the late 19th century

- Alexandre Promio was one of the first filmmakers to use camera movement, though this particular film appears to be stationary

- The Cinématographe used to film this was both a camera, projector, and developer - a revolutionary all-in-one device

- Children were popular subjects in early cinema as they represented innocence and the future

- The film was likely shown as part of a program of 10-15 short films that made up a typical Lumière screening

- Promio traveled extensively for the Lumière company, filming in locations from Spain to Russia

- This film survives today and is preserved in film archives, making it accessible to modern audiences

- The simple activity depicted represents the Lumière philosophy of capturing 'life as it is'

- Early films like this were often projected with live musical accompaniment, typically piano or small orchestra

- The film's title in French was likely 'Enfants pêchant des palourdes'

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception of this film would have been part of the general wonder and amazement that greeted early motion pictures. Critics and audiences of 1896 were primarily amazed by the technology itself rather than evaluating artistic merit. The ability to see moving images of real people and activities was considered miraculous. Modern film historians and critics view this film as an important artifact of cinema's birth, appreciating its documentary value and its role in establishing actuality film as a genre. The film is now studied as an example of early cinematic technique and as a window into late 19th-century life. While it lacks narrative complexity, its simplicity and authenticity are valued by contemporary scholars of early cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Original audiences in 1896 would have been fascinated by this film's ability to capture and reproduce motion, regardless of the subject matter. The sight of children moving naturally on screen would have been astonishing to viewers who had never experienced motion pictures before. The familiar activity of clam digging would have made the magical technology of cinema more accessible and relatable. Modern audiences viewing this film in archives or screenings of early cinema appreciate it as a historical document and a connection to cinema's origins. The film's brevity and simplicity make it accessible to contemporary viewers, who often find charm in its authenticity and technical limitations.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Lumière brothers' actuality film tradition

- Early documentary photography

- Ethnographic documentation practices

This Film Influenced

- Other Lumière actuality films

- Early documentary cinema

- Ethnographic films

- Children in cinema documentaries

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Preserved in film archives, including the Lumière Institute in Lyon, France. The film survives in 35mm format and has been digitized for preservation and access purposes. As part of the Lumière collection, it has received professional archival care and restoration to ensure its survival for future generations.