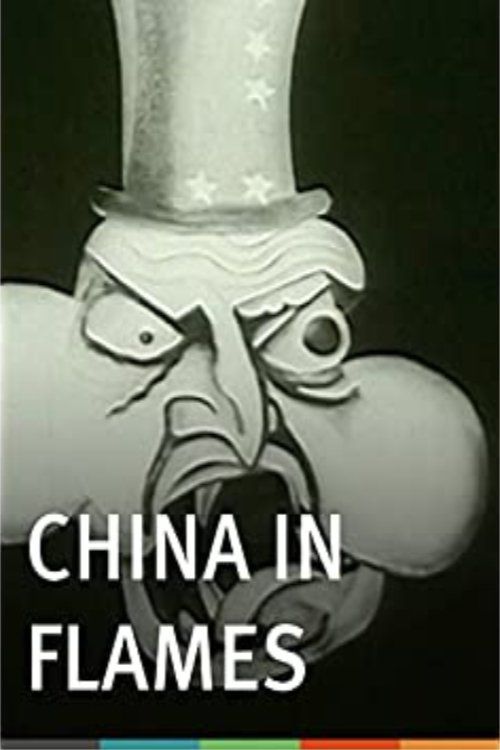

China in Flames

Plot

China in Flames is a Soviet animated propaganda film that depicts the struggle of Chinese workers and peasants against foreign imperialists and domestic oppressors. The film uses powerful allegorical imagery to show the Chinese revolution unfolding, with animated characters representing different social classes and political forces. Through a series of dramatic vignettes, the cartoon portrays the awakening of Chinese consciousness, the brutal suppression by reactionary forces, and the ultimate triumph of the revolutionary masses. The animation culminates in a symbolic sequence showing China breaking free from its chains and joining the international proletarian movement. The film serves as both a call to solidarity with the Chinese revolution and a celebration of Marxist-Leninist ideology.

Director

About the Production

Created using cut-out animation techniques with paper cutouts, a method pioneered by Soviet animators due to resource constraints. The film was produced during a period of intense Soviet interest in supporting revolutionary movements worldwide. Khodataev and his team worked with limited materials, using whatever paper and ink was available. The animation was hand-colored frame by frame, requiring meticulous attention to detail. The production team included several artists who would become pioneers of Soviet animation.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1925 during a critical period in both Soviet and Chinese history. In the Soviet Union, this was the NEP (New Economic Policy) era, when the government was actively supporting revolutionary movements worldwide as part of Comintern activities. In China, 1925 saw the height of the May Thirtieth Movement, a massive anti-imperialist protest movement that followed the shooting of Chinese protesters by British police in Shanghai. The Soviet Union was providing significant support to both the Chinese Communist Party and the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) through the First United Front alliance. This film was part of a broader Soviet propaganda effort to rally international support for the Chinese revolution and to portray the Soviet Union as the leader of worldwide anti-imperialist struggle. The animation reflects the optimistic Soviet view that China was on the verge of a successful socialist revolution.

Why This Film Matters

China in Flames represents an important milestone in the history of both Soviet animation and political cinema. As one of the earliest examples of animated propaganda, it demonstrates how the new medium of animation was quickly embraced for political messaging. The film's technical innovations in cut-out animation influenced generations of Soviet animators and established techniques that would be used for decades. Culturally, it reflects the internationalist perspective of early Soviet policy and the genuine belief in world revolution that characterized the 1920s. The film also represents an early example of cross-cultural political solidarity in cinema, using animation to bridge geographical and linguistic barriers. Its preservation and study today provides valuable insight into early Soviet visual culture, propaganda techniques, and the international communist movement's cultural production.

Making Of

China in Flames was created during the early days of Soviet animation when resources were extremely limited. Director Nikolai Khodataev and his small team developed innovative cut-out animation techniques using paper cutouts moved under a camera frame by frame. The production took place in a makeshift studio in Moscow with basic equipment. The artists studied Chinese political cartoons and newspaper reports to create authentic-looking characters and settings. The animation was hand-colored using stencils, a laborious process that required each frame to be individually painted. The film's soundtrack, if any originally existed, has been lost, as was common with early Soviet films. The production team worked closely with political commissars to ensure the film's message aligned with official Soviet policy toward China and the international communist movement.

Visual Style

The film utilized cut-out animation techniques with paper characters moved frame by frame against painted backgrounds. The visual style was influenced by both Russian constructivist art and Chinese political cartoons of the period. The animation featured bold, contrasting colors with red dominating to symbolize revolution. The camera work was relatively static due to technical limitations, but the animators created dynamic movement through the careful positioning of cut-outs. The visual composition emphasized symbolic imagery over realistic representation, using exaggerated gestures and expressions to convey political meaning. The film's aesthetic reflected the avant-garde artistic movements flourishing in 1920s Soviet Russia.

Innovations

The film pioneered advanced cut-out animation techniques in Soviet cinema. Khodataev developed methods for creating more fluid movement and emotional expression using paper cut-outs than had been previously achieved. The team created innovative joint systems for character cut-outs that allowed for more natural movement. The hand-coloring process used stencils to ensure consistent color application across thousands of animation frames. The film demonstrated how complex political narratives could be conveyed through visual storytelling without dialogue, an important achievement for international propaganda. The production also developed time-saving techniques for background creation that influenced later Soviet animation studios.

Music

Original musical accompaniment details are unknown, which was common for silent era films. The film would have been accompanied by live music during screenings, typically piano or organ music played by a musician who may have improvised or used suggested cue sheets. Given the film's political nature, the musical accompaniment likely included revolutionary songs of the period, possibly including 'The Internationale' or other workers' anthems. Some screenings may have included a narrator explaining the scenes to audiences, as was common with Soviet propaganda films of this era.

Famous Quotes

The film contains no dialogue, relying on visual symbolism and intertitles that read: 'China awakens!' and 'Workers of the world, unite!'

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic sequence where animated Chinese workers break their chains and raise the red flag, symbolizing revolutionary victory and international solidarity.

Did You Know?

- One of the earliest surviving examples of Soviet political animation

- Director Nikolai Khodataev was a pioneer of cut-out animation technique

- The film was part of a series of Soviet propaganda animations supporting international revolutionary movements

- Created during the First United Front period in China when Communists and Nationalists were allied

- The animation techniques used influenced later Soviet animators including Ivan Ivanov-Vano

- The film was screened at workers' clubs and political meetings rather than commercial theaters

- Original film elements were believed lost for decades before being rediscovered in Soviet archives

- The Chinese characters in the film were based on contemporary newspaper photographs and political cartoons

- The film's color scheme used red prominently to symbolize communism and revolution

- Khodataev later became a teacher at the Soviet state film school (VGIK)

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its powerful political message and innovative animation techniques. Reviews in publications like 'Kino' and 'Pravda' highlighted the film's effectiveness as propaganda and its artistic merit. International communist publications also noted the film as an example of Soviet cultural achievement. Later film historians have recognized China in Flames as a significant work in the development of animation, particularly for its sophisticated use of cut-out techniques to convey complex political narratives. Modern critics appreciate the film both as a historical document and as an example of early animation artistry, though they also note its overt propagandistic nature typical of its era.

What Audiences Thought

The film was primarily shown to Soviet workers, soldiers, and political party members at special screenings rather than general commercial audiences. Reports from the period indicate that audiences responded positively to the film's patriotic and internationalist themes. The animation's visual style and dramatic storytelling made it accessible even to semi-literate viewers, which was important for Soviet propaganda goals. The film was also shown at international workers' meetings and communist party congresses outside the Soviet Union, where it reportedly generated enthusiasm for supporting the Chinese revolution. Contemporary accounts suggest that Chinese students and revolutionaries who saw the film appreciated the Soviet solidarity it represented.

Awards & Recognition

- None documented - propaganda films of this era typically did not participate in award competitions

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet political poster art

- Chinese political cartoons

- Constructivist art movement

- Earlier Soviet propaganda films

- German expressionist animation

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet propaganda animations

- Chinese revolutionary animations of the 1930s

- International communist propaganda films

- Modern political animation

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved in the Russian State Film Archive (Gosfilmofond). Digital restoration was completed in the early 2000s as part of a Soviet animation preservation project. While some color deterioration has occurred, the film remains largely intact and viewable. The restoration has made the film available for scholarly study and archival screenings.