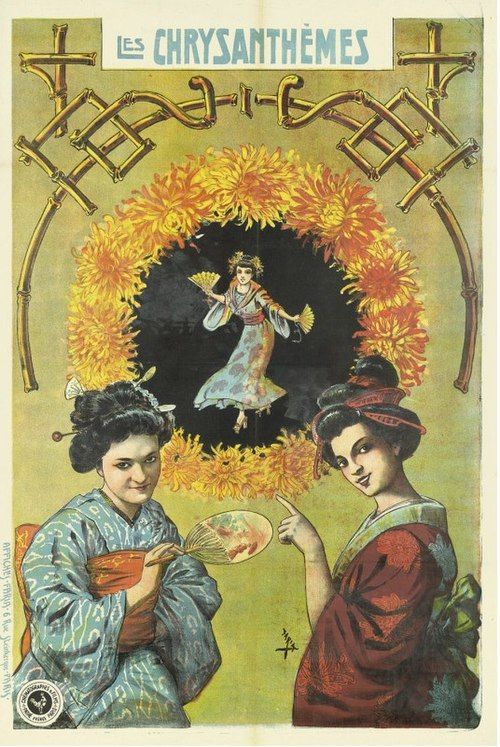

Chrysanthemums

Plot

In this magical trick film, two ornate vases rise from a stage and separate to reveal female dancers positioned behind each. The dancers create enchanted circles of flowers, from which additional women mysteriously emerge. Together, the performers construct an elaborate floral display, featuring a miniature dancer performing in the center. The film culminates with another circle of flowers advancing toward the camera, showcasing a series of women within, before the original pair of dancers conclude their performance by elegantly twirling their parasols in a synchronized finale.

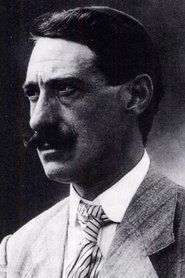

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed using early special effects techniques including multiple exposures, substitution splices, and matte photography. The film was shot on black-and-white film stock and may have been hand-colored for release. As with many Pathé productions of this era, the film was likely shot in a studio setting with controlled lighting to achieve the magical effects.

Historical Background

1907 was a pivotal year in early cinema, marking the transition from simple actualities to more complex narrative and trick films. The film industry was rapidly evolving from fairground attractions to theatrical presentations. Segundo de Chomón was working at Pathé Frères during their golden age, when the French company dominated global film production. This period saw intense competition between filmmakers like Georges Méliès and de Chomón to create increasingly elaborate visual effects. The film emerged during the Belle Époque in France, a time of artistic innovation and technological optimism that influenced the magical, fantastical themes popular in cinema of the era.

Why This Film Matters

'Chrysanthemums' represents an important milestone in the development of visual effects in cinema. As part of the trick film genre, it helped establish many techniques that would become fundamental to filmmaking. The film exemplifies the early 20th century fascination with magic, illusion, and the seemingly impossible made possible through technology. It contributed to the evolution of cinema from simple documentation to a medium capable of creating complete fantasy worlds. The film also reflects the gender dynamics of early cinema, where women like Julienne Mathieu were prominent performers and central to the visual spectacle. Its preservation and study today helps us understand the origins of cinematic language and special effects.

Making Of

The creation of 'Chrysanthemums' involved sophisticated early special effects techniques that were revolutionary for 1907. Segundo de Chomón, working at Pathé Frères, employed multiple exposure photography to create the illusion of dancers appearing from nowhere. The film required precise timing and choreography, as each substitution splice needed to be perfectly executed. The sets were designed with trap doors and hidden mechanisms to facilitate the magical appearances. Julienne Mathieu, as the lead performer, had to master not just dancing but also the precise timing required for the special effects to work seamlessly. The production team would have spent considerable time planning each shot, as any mistake in the effects would require reshooting the entire sequence.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Chrysanthemums' employed static camera positioning typical of early cinema, with the camera fixed to capture the stage-like presentation. The lighting was carefully arranged to highlight the magical effects and create contrast for the special effects to work effectively. The film likely used multiple exposure techniques and substitution splices to create the illusion of dancers appearing from flowers. The visual composition was theatrical, with performers arranged symmetrically for maximum visual impact. The black-and-white photography was probably enhanced with hand-coloring for the floral elements, a common practice in Pathé productions of this era.

Innovations

'Chrysanthemums' showcases several important technical achievements in early cinema. The film demonstrates sophisticated use of substitution splices, where the camera is stopped and restarted to create magical transformations. Multiple exposure techniques were used to create the illusion of multiple performers appearing simultaneously. The film also features early use of matte photography and forced perspective to create the miniature dancer effect. These techniques, while common in de Chomón's work, were at the cutting edge of cinematic technology in 1907. The film's success in creating seamless magical illusions contributed to the development of special effects that would become standard in later cinema.

Music

As a silent film from 1907, 'Chrysanthemums' would have been accompanied by live music during exhibition. The musical accompaniment would typically have been provided by a pianist, organist, or small ensemble in the venue. The music would have been selected to match the magical, graceful nature of the on-screen action, likely featuring waltzes or other light classical pieces popular during the Belle Époque. No original score was composed specifically for the film; instead, exhibitors would choose appropriate music from their existing repertoire.

Memorable Scenes

- The magical emergence of dancers from the flower circles, showcasing de Chomón's mastery of substitution splices and multiple exposures to create the illusion of performers appearing from nowhere in a cascade of floral beauty

Did You Know?

- This film is part of the 'trick film' genre popular in early cinema, where filmmakers used camera tricks to create magical illusions

- Segundo de Chomón was often called 'the Spanish Méliès' due to his similar style to Georges Méliès

- Julienne Mathieu was not only the star but also de Chomón's wife and frequent collaborator

- The film showcases early use of substitution splice techniques, where the camera is stopped, objects are changed, and filming resumes

- Pathé Frères was one of the most important film production companies in early cinema

- The parasols used in the film were likely props designed to catch and reflect light for maximum visual impact

- Many of these early films were hand-colored frame by frame, a laborious process that added to their magical quality

- The miniature dancer effect was achieved using forced perspective and careful camera positioning

- De Chomón was a pioneer in developing many special effects techniques still used today

- The film was likely distributed internationally, as Pathé had extensive global distribution networks

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception for such short films in 1907 is difficult to trace, as film criticism was not yet established as we know it today. However, trick films like 'Chrysanthemums' were generally well-received by audiences and exhibitors for their entertainment value and technical innovation. Modern film historians and scholars recognize de Chomón's work as technically sophisticated for its time, with particular appreciation for his mastery of special effects and his contribution to the development of cinematic language. The film is now studied as an important example of early trick film aesthetics and the international exchange of cinematic techniques between France and Spain.

What Audiences Thought

Early audiences in 1907 were typically amazed and delighted by trick films like 'Chrysanthemums,' which offered visual spectacles unlike anything they had seen before. The magical appearance and disappearance of performers would have been genuinely surprising to viewers unfamiliar with cinematic techniques. These films were popular attractions in music halls, fairgrounds, and early cinemas. The combination of dance, magic, and floral imagery appealed to the aesthetic sensibilities of the Belle Époque audience. The short format made it ideal for the variety-style programming common in early cinema exhibition.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès' trick films

- Stage magic traditions

- Ballet and theatrical dance

- Art Nouveau aesthetics

This Film Influenced

- Later trick films by various directors

- Fantasy films of the 1910s

- Early Disney animation techniques

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in various film archives, including the Cinémathèque Française. As a Pathé production, it has likely survived in better condition than many independent films from the era. Some versions may be available in restored or digitized formats for scholarly study and public viewing.