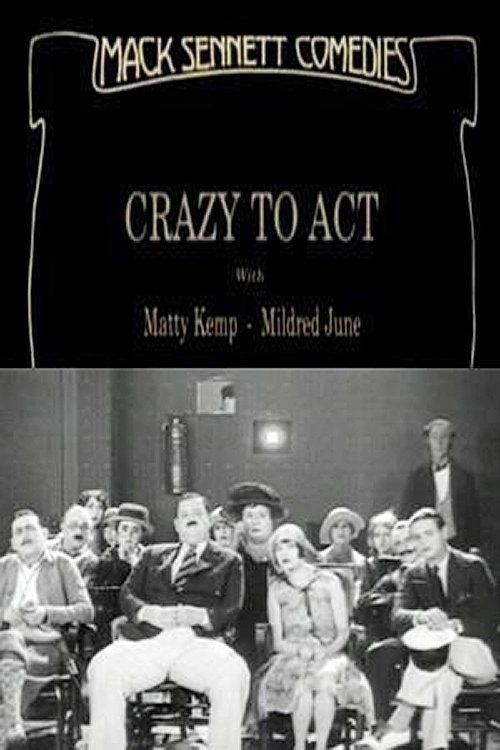

Crazy to Act

"A Comedy of Hollywood Madness!"

Plot

Millionaire film producer Gordon Bagley becomes infatuated with Ethel St. John, the beautiful leading lady in his latest motion picture production. However, Ethel's heart belongs to Arthur Young, the handsome hero who stars opposite her in Bagley's film. As production on the movie continues, the romantic tensions behind the scenes begin to mirror the on-screen drama. When the completed film is previewed for industry insiders, it proves to be an unmitigated disaster, humiliating Bagley and threatening his reputation. In the aftermath, Ethel decides to leave with Arthur, choosing love over career advancement. The film culminates with the dejected Gordon Bagley literally running endlessly on a rotating movie set, a perfect metaphor for his circular predicament and the cyclical nature of Hollywood dreams.

About the Production

This was one of Oliver Hardy's solo comedy shorts before his permanent partnership with Stan Laurel. The film was produced during the transition period from shorts to features and utilized standard silent era production techniques. The rotating set gag in the finale was achieved through practical effects that were innovative for the time, requiring precise engineering to create the illusion of endless running.

Historical Background

1927 was a watershed year in cinema history, representing the absolute peak of the silent film era just before the sound revolution would permanently transform the industry. Hollywood was experiencing unprecedented creative and commercial success, with studios like MGM, Paramount, and Fox dominating the landscape. Comedy shorts were a crucial part of theatrical programming, serving as appetizers before feature presentations. This film emerged during the golden age of slapstick comedy, when stars like Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd were at their zenith. The year also saw the release of 'The Jazz Singer,' which would soon make films like 'Crazy to Act' technically obsolete. Behind the scenes, the studio system was firmly entrenched, with actors often under long-term contracts and working across multiple genres. The film's meta-commentary on Hollywood reflects an industry that was becoming increasingly self-aware and sophisticated in its storytelling.

Why This Film Matters

While 'Crazy to Act' was a relatively minor comedy short, it holds cultural significance as a document of the late silent era and as a showcase of Oliver Hardy's pre-Laurel work. The film's behind-the-scenes look at Hollywood production offers valuable insight into the filmmaking practices of the 1920s, preserving techniques and working methods that would soon disappear with the advent of sound. The meta-narrative approach, focusing on the film industry itself, represents an early example of Hollywood's self-reflexive tendencies that would become more pronounced in later decades. For comedy historians, the film demonstrates the transitional state of screen comedy, moving away from the pure slapstick of the teens toward more character-driven humor. The rotating set gag, while simple by modern standards, represents the kind of technical ingenuity that defined silent comedy's visual innovation. Most significantly, the film serves as a time capsule of Oliver Hardy's development as a comic performer, showing the skills and persona he would later perfect in his partnership with Stan Laurel.

Making Of

The production of 'Crazy to Act' took place during a fascinating transitional period in Hollywood history. Director Earle Rodney, who had honed his skills writing for comedy legends like Harold Lloyd, brought a sophisticated understanding of comedic timing to this modest two-reeler. The rotating set sequence required significant technical planning and engineering, with the crew building a massive circular platform that could be rotated manually or mechanically while Hardy performed his exhausting running gag. Oliver Hardy, who had been working in comedy shorts for over a decade, was at this point a reliable character actor but had not yet developed the persona that would make him world-famous. The film was shot quickly and economically, as was typical for comedy shorts of the era, with the cast and crew often working on multiple projects simultaneously. The meta-commentary on Hollywood filmmaking was relatively sophisticated for its time, suggesting the filmmakers had an insider's perspective on the industry's absurdities.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Crazy to Act' employed standard silent era techniques but showed particular skill in the film's more ambitious sequences. The camera work was functional rather than artistic, as was typical for comedy shorts that prioritized clear presentation of gags over visual poetry. The rotating set sequence required careful camera placement to maintain the illusion of endless running while keeping Hardy properly framed. Intertitles were used judiciously to advance the plot without disrupting the flow of physical comedy. The film likely used natural lighting where possible, supplemented by the harsh studio lighting characteristic of the period. The cinematographer would have needed to coordinate closely with the director to ensure the complex mechanical effects were captured effectively. While not innovative by the standards of prestige features, the photography successfully served the comedy's needs and demonstrated the professional craftsmanship expected of major studio productions of the era.

Innovations

The most notable technical achievement in 'Crazy to Act' was the engineering and execution of the rotating set sequence in the film's finale. This practical effect required building a large circular platform that could be rotated continuously while Oliver Hardy performed his running gag. The mechanism needed to be both reliable enough for multiple takes and safe for the performer. The film also demonstrated competent use of editing techniques common to the era, including match cuts and continuity editing to maintain narrative flow. The meta-narrative structure, showing the making of a film within a film, required careful coordination between the various levels of reality being presented. While not groundbreaking by the standards of major features of the period, these technical elements showed the sophistication that had developed in comedy short production by the late 1920s. The film's preservation of behind-the-scenes filmmaking techniques also provides valuable documentation of silent era production methods.

Music

As a silent film, 'Crazy to Act' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The score would typically have been provided by a theater's house organist or pianist, using compiled cue sheets or improvisation based on the film's action. For a comedy short, the music would have been upbeat and playful, with popular songs of the era possibly incorporated. The rotating set sequence would have required particularly dynamic musical accompaniment to enhance the comic effect of Hardy's endless running. Large urban theaters might have had small orchestras perform more elaborate arrangements. The music would have followed the dramatic structure of the film, becoming more romantic during the scenes between Ethel and Arthur, more frantic during the disastrous screening, and reaching a crescendo during the finale. No original composed score exists for the film, as was standard practice for shorts of this period.

Famous Quotes

"In Hollywood, everyone's crazy to act - either on screen or in love!"

"My film's a disaster, but my heart's a bigger catastrophe!"

"She chose the hero over the producer... I should have written a better ending!"

Memorable Scenes

- The disastrous preview screening where the audience reacts with horror and laughter to the terrible film

- Oliver Hardy's endless running on the rotating set, creating a surreal metaphor for his predicament

- The behind-the-scenes chaos during the film-within-the-film's production

- The romantic confrontation between the producer, actress, and leading man

Did You Know?

- This film was released just months before Oliver Hardy began his legendary partnership with Stan Laurel, making it one of his final solo starring vehicles

- The rotating set gag in the finale was an early example of what would become a recurring trope in comedy films

- Director Earle Rodney was also a prolific comedy writer who contributed to numerous Harold Lloyd films

- Matty Kemp was a popular juvenile lead of the 1920s who later became a talent agent

- The film's meta-narrative about filmmaking was relatively uncommon for comedy shorts of the era

- Pathé Exchange distributed the film as part of their comedy series, competing with Hal Roach and Mack Sennett productions

- The movie was filmed during the peak of silent cinema, just before 'The Jazz Singer' would revolutionize the industry

- Oliver Hardy plays against type as a romantic lead rather than his later comic foil character

- The film's title 'Crazy to Act' refers both to the characters' romantic decisions and the business of filmmaking itself

- Only incomplete copies of this film are known to survive, making full appreciation of its techniques difficult for modern viewers

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception for 'Crazy to Act' was modest, as was typical for comedy shorts of the era. Trade publications like Variety and Motion Picture News generally gave it brief, positive mentions, noting its competent execution and Hardy's reliable performance. The film was praised for its clever premise about Hollywood life, with some critics appreciating the insider humor about film production. However, it was not considered groundbreaking or exceptional compared to the work of major comedy stars of the period. Modern critical assessment is limited due to the film's incomplete survival status, but comedy historians recognize it as an interesting example of late silent comedy and a valuable document of Oliver Hardy's solo career. The film is generally regarded as competent but not exceptional, representing the solid craftsmanship of second-tier comedy production rather than the innovation of top-tier studios like Hal Roach or Mack Sennett.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to 'Crazy to Act' in 1927 was likely positive but unexceptional, as the film served its purpose as part of a comedy short program. Theater-goers of the era expected brief, entertaining diversions between features, and this film delivered on those expectations. Oliver Hardy was a recognizable and popular character actor, though not yet the star he would become, and his presence would have been a draw for regular moviegoers. The film's Hollywood setting would have appealed to audiences' fascination with the movie industry, which was at its peak of glamour and mystery during the 1920s. The physical comedy, particularly the rotating set sequence, would have generated the expected laughs from contemporary audiences. However, there's no evidence that the film achieved any exceptional popularity or became particularly memorable to audiences of the time, as it was one of hundreds of similar shorts produced annually during the silent era.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The General (1926) - for its technical innovation

- The Freshman (1925) - for its Hollywood satire

- Sherlock Jr. (1924) - for its meta-cinematic elements

This Film Influenced

- Early Laurel and Hardy shorts - showing Hardy's character development

- Hollywood satire films of the 1930s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Incomplete - only fragments and portions of 'Crazy to Act' are known to survive in film archives. The film is considered partially lost, with some key sequences possibly missing entirely. What remains is preserved at the Library of Congress and other film archives, but a complete, restored version is not available to the public.