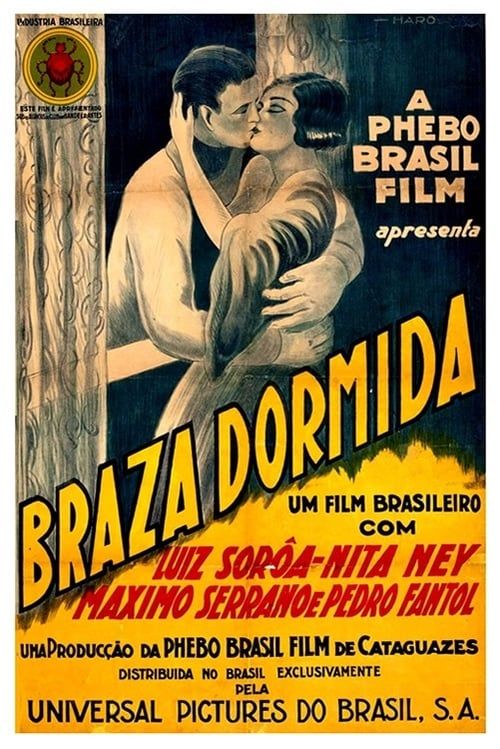

Dormant Embers

Plot

A young man from Rio de Janeiro, facing financial hardship in the bustling capital, accepts a position as manager of a remote sugar mill in the Brazilian countryside. There, he discovers not only a new way of life but also falls deeply in love with the mill owner's beautiful daughter. Their budding romance faces obstacles when the mill's former manager, who was demoted due to incompetence, becomes consumed by jealousy and resentment. Determined to reclaim his position and destroy the new manager's happiness, the bitter former employee begins systematically sabotaging the mill's operations, creating a tense atmosphere of suspicion and danger. The young protagonist must navigate both professional challenges and personal threats while protecting his love and proving his worth to the community that has welcomed him.

About the Production

Filmed during the golden age of Brazilian silent cinema, this production faced the typical challenges of the era including limited equipment, natural lighting challenges, and the need to shoot sequentially due to film stock constraints. The sugar mill location required extensive scouting to find an authentic working plantation that could accommodate a film crew.

Historical Background

1928 Brazil was a nation in transition, with the Old Republic (1889-1930) nearing its end and significant social changes underway. The country was experiencing rapid urbanization, particularly in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, while rural areas maintained traditional agricultural economies. This film captured the tension between modern urban life and traditional rural existence, a central theme in Brazilian society of the 1920s. The Brazilian film industry was still in its infancy, with most productions imitating European or American styles. Mauro's work, including 'Brasa Dormida,' was groundbreaking for its focus on distinctly Brazilian themes and settings. The year 1928 also saw the introduction of sound technology in international cinema, making this film part of the final wave of Brazilian silent productions before the technical and artistic challenges of sound cinema would transform the industry.

Why This Film Matters

'Brasa Dormida' represents a crucial milestone in the development of Brazilian national cinema as it moved away from simply imitating foreign models toward creating authentically Brazilian narratives. The film's focus on rural life, the sugar economy, and the tensions between tradition and modernity helped establish a cinematic language that spoke to Brazilian experiences. Humberto Mauro's approach influenced generations of Brazilian filmmakers, particularly the Cinema Novo movement of the 1960s, which also sought to create a distinctly Brazilian cinema. The film's portrayal of regional diversity and social dynamics contributed to a broader cultural understanding of Brazil's complex identity. Its status as a partially lost film has made it legendary in Brazilian film studies circles, symbolizing both the richness and fragility of early Brazilian cinema heritage.

Making Of

Humberto Mauro approached 'Brasa Dormida' with his characteristic attention to regional authenticity, insisting on filming at an actual working sugar plantation rather than on studio sets. The production faced significant logistical challenges transporting heavy camera equipment to rural locations. Cast members had to learn the actual processes of sugar production to perform their roles convincingly. The romantic scenes between Luis Soroa and Nita Ney were reportedly difficult to film due to the strict social conventions of 1920s Brazil, requiring the director to find creative ways to suggest intimacy without offending sensibilities. The sabotage sequences involved real mill machinery, creating genuine danger for the actors and crew. Mauro's innovative use of natural light, particularly in the outdoor scenes, was noted by contemporary critics as particularly advanced for Brazilian cinema of the period.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Edgar Brasil, was considered revolutionary for its time in Brazilian cinema. Brasil employed natural lighting techniques that were quite advanced for the period, particularly in the outdoor scenes at the sugar mill. The film made effective use of the Brazilian landscape, with sweeping shots of the sugar cane fields that emphasized both the beauty and the harshness of rural life. Interior scenes were carefully composed to create dramatic tension, particularly during the sabotage sequences. The camera work showed influences from German Expressionism in its use of shadows and angles during moments of conflict, while maintaining a more naturalistic style for the romantic scenes. The surviving fragments demonstrate a sophisticated visual style that was years ahead of most contemporary Brazilian productions.

Innovations

The film demonstrated several technical innovations for Brazilian cinema of its era. Mauro and his cinematographer Edgar Brasil developed new techniques for filming in bright tropical sunlight, using diffusers and reflectors to control the harsh Brazilian sun. The production pioneered location shooting in difficult rural conditions, establishing methods that would influence subsequent Brazilian filmmakers. The film's editing was particularly sophisticated for its time, using cross-cutting techniques to build tension during the sabotage sequences. The special effects used to show the mill machinery problems were innovative for Brazilian cinema, involving practical effects rather than the optical techniques more common in larger productions. The film also experimented with different film stocks to achieve various visual effects, a relatively advanced technique for the period.

Music

As a silent film, 'Brasa Dormida' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The typical Brazilian cinema of this era employed small orchestras or pianists who would play a combination of popular Brazilian songs of the period, classical pieces, and specially composed cues. The music likely included choro and maxixe styles that were popular in Rio de Janeiro during the 1920s, particularly for the urban scenes, while rural scenes might have incorporated modinha and folk melodies. The score would have been crucial in establishing emotional tone, particularly during the romantic and suspenseful sequences. Unfortunately, no written records of the original musical accompaniment survive, though contemporary accounts suggest it was particularly effective in enhancing the film's dramatic moments.

Famous Quotes

No interior do Brasil, a vida tem um ritmo que a cidade não compreende

O ciúme é como fogo em cana seca - destrói tudo ao seu redor

O amor floresce onde menos se espera, como flor em terra árida

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic sequence where the former manager sabotages the sugar mill machinery, creating tension through cross-cutting between the breaking equipment and the oblivious lovers

- The romantic scene in the sugar cane fields at sunset, showcasing innovative use of natural lighting

- The confrontation scene between the two managers in the mill office, utilizing German Expressionist lighting techniques

- The final scene where the mill is saved and the lovers are reunited, featuring elaborate tracking shots through the working mill

Did You Know?

- The film's Portuguese title is 'Brasa Dormida,' which literally translates to 'Sleeping Ember,' a more poetic version of the English 'Dormant Embers'

- Director Humberto Mauro is considered one of the three pioneers of Brazilian cinema, alongside Adhemar Gonzaga and Mário Peixoto

- The film was one of the last major Brazilian silent productions before the transition to sound cinema

- Nita Ney, who played the female lead, was one of Brazil's first major film stars and was known as 'The Brazilian Mary Pickford'

- The sugar mill setting was significant as it represented Brazil's agricultural economy and rural-urban divide during the 1920s

- The film's negative and most prints were lost in a fire at Cinematográfica Brasileira's facilities in the 1930s

- Only incomplete fragments and still photographs from the production survive today

- The film was part of Mauro's 'regional trilogy' focusing on different aspects of Brazilian life

- Contemporary reviews praised the film's authentic portrayal of rural Brazil

- The jealousy subplot was considered quite daring for its time in its psychological complexity

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'Brasa Dormida' for its technical sophistication and authentic Brazilian character. The newspaper 'O Jornal do Brasil' hailed it as 'the most Brazilian film yet produced,' while 'A Noite' particularly commended Mauro's direction and the performances of the lead actors. Critics noted the film's effective use of natural scenery and its avoidance of theatrical acting styles common in earlier Brazilian productions. Modern film historians consider it a masterpiece of the silent era, with many lamenting its incomplete preservation status. The film is frequently cited in academic studies of Brazilian cinema as a prime example of the country's early attempts to develop its own cinematic identity, distinct from American and European influences.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by urban audiences in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, who were fascinated by its authentic portrayal of rural Brazilian life. Many viewers from rural areas appreciated seeing their own experiences and environments represented on screen for the first time. The romantic storyline proved particularly popular, with the chemistry between Luis Soroa and Nita Ney becoming a talking point among moviegoers. The film ran for several weeks in major cinemas, an unusual success for a Brazilian production of the period, which typically struggled against imported American films. Audience letters published in newspapers of the time praised the film's emotional depth and technical quality, with many expressing pride in a Brazilian production that could compete with foreign films.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Brazilian Film - Rio de Janeiro Film Critics Circle (1928)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema (for dramatic lighting)

- Soviet montage theory (for editing techniques)

- American melodrama (for narrative structure)

- Italian neorealism (for authentic locations)

- Brazilian literature (regionalist writing tradition)

This Film Influenced

- Ganga Bruta (1933)

- Limite (1931)

- Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol (1964)

- Vidas Secas (1963)

- O Pai de Família (1971)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Partially lost film - only fragments and still photographs survive. The original negative was destroyed in a fire at the Cinematográfica Brasileira facilities in the 1930s. Some incomplete reels were discovered in the 1970s at the Cinemateca Brasileira, but approximately 60% of the film remains missing. The surviving fragments have been partially restored and are preserved at the Cinemateca Brasileira in São Paulo.