Drama at the Bottom of the Sea

Plot

In this groundbreaking early underwater film, two divers descend to the ocean floor in search of treasure, their movements captured through innovative blue-tinted cinematography that creates the illusion of being beneath the waves. The peaceful exploration quickly turns violent as the divers discover a chest of gold, leading to a brutal axe fight between the two men as they struggle for possession of the treasure. The combat intensifies as they grapple underwater, their heavy diving gear and weapons creating a deadly ballet beneath the sea. Ultimately, one diver emerges victorious after killing his rival, claiming the treasure for himself in a surprisingly graphic conclusion for its era. The film's underwater setting and violent content made it stand out among the simple trick films of its time.

Director

About the Production

Filmed using early special effects techniques including blue tinting to simulate underwater environment. The diving sequences were likely shot in a glass tank or through painted glass effects. The violent axe combat was unusually graphic for 1901 cinema. Pathé's studio facilities in Vincennes, France, were used for most of their productions during this period.

Historical Background

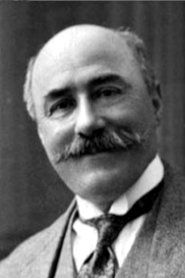

In 1901, cinema was still in its infancy, with most films being simple actualities or brief trick films lasting only a minute or two. The Pathé company, founded by Charles Pathé, was rapidly expanding its global reach and experimenting with new genres and techniques. This period saw the development of narrative cinema, with filmmakers like Georges Méliès and Ferdinand Zecca pushing the boundaries of what could be achieved with the medium. The film was created during the Belle Époque in France, a time of artistic innovation and technological advancement. Early cinema audiences were fascinated by any form of visual spectacle, making films with exotic locations or unusual effects particularly popular.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important milestone in the development of narrative cinema and special effects. It demonstrates early filmmakers' creativity in overcoming technical limitations, particularly in creating the illusion of underwater scenes before underwater photography was possible. The film's violent content, while shocking for its time, helped establish cinema as a medium capable of depicting intense human drama and conflict. It also contributed to the development of the adventure and treasure hunt genres that would become staples of cinema throughout the 20th century. The hand-tinting technique used in this film was an early example of color in cinema, predating more sophisticated color processes by decades.

Making Of

Ferdinand Zecca, who had joined Pathé in 1899, was experimenting with various film genres and techniques during this period. The underwater sequences were created using a combination of methods: actors performed behind glass panels with painted backgrounds, and the entire film was then tinted blue by hand, frame by frame, to create the underwater atmosphere. The diving suits were authentic heavy equipment that would have been extremely uncomfortable for the actors to wear during filming. The violent axe combat required careful choreography to appear realistic while ensuring actor safety. The treasure chest props were likely filled with lightweight materials rather than actual gold to make them easier to handle during the fight sequences.

Visual Style

The cinematography was innovative for its time, using blue hand-tinting throughout to create the underwater atmosphere. The camera work was static, as was typical for 1901, but the composition carefully framed the action to maximize the dramatic impact. The underwater effect was enhanced by using glass tanks, painted backgrounds, and careful lighting techniques. The blue tinting process required each frame to be colored by hand, making it an expensive and time-consuming production for its era.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was the convincing underwater illusion created without underwater cameras. The hand-tinting process for the entire film was a significant undertaking for 1901. The use of authentic diving equipment and realistic fight choreography demonstrated advances in production design and stunt coordination. The film also showed early mastery of continuity editing within its brief runtime, maintaining clear narrative progression despite the technical limitations of the period.

Music

Like all films of 1901, this was a silent production. Musical accompaniment would have been provided live by pianists or small orchestras in theaters, typically using popular classical pieces or improvised music that matched the on-screen action. The underwater scenes would likely have been accompanied by mysterious, flowing music, while the combat scenes would have featured more dramatic and intense musical selections.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue)

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic underwater axe fight between the two divers, with blue-tinted frames creating the illusion of combat beneath the waves, ending with one diver's victory over the treasure chest

Did You Know?

- This film is also known by its French title 'Drame au fond de la mer'

- The blue tinting was achieved by hand-coloring each frame, a laborious process for 1901

- The underwater effect was created before underwater cameras were invented, using clever studio techniques

- The film's violence was considered shocking even for early cinema audiences

- Pathé Frères was the largest film production company in the world at the time

- The diving equipment shown was authentic for the period, likely borrowed from actual divers

- This film represents one of the earliest examples of the treasure hunt genre in cinema

- The axe fight choreography was surprisingly sophisticated for such an early film

- The film was distributed internationally, helping establish Pathé's global dominance

- Only fragments of the original print are believed to survive today

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews from 1901 are scarce, but trade publications noted the film's impressive underwater effects and dramatic content. Modern film historians recognize it as an innovative example of early special effects and narrative development. The film is often cited in studies of early cinema violence and the evolution of the adventure genre. Critics have noted how the film's relatively complex narrative and technical achievements set it apart from simpler productions of the era.

What Audiences Thought

Early cinema audiences were reportedly shocked and fascinated by the film's violent content and underwater effects. The combination of exotic underwater setting and dramatic combat made it popular among fairground and theater audiences. The film's brief but intense nature made it ideal for the variety show format common in early cinema exhibition. Audience reactions helped establish that there was a market for more dramatic and violent content in motion pictures.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès' trick films

- Stage melodramas

- Adventure literature

- Underwater exploration narratives

This Film Influenced

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1907)

- The Deep Sea (1916)

- Underwater adventure films of the 1920s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with some scenes missing. Fragments exist in film archives including the Cinémathèque Française. The surviving footage shows signs of deterioration typical of nitrate film from this period. Some restoration work has been done, but the complete original version may be lost.