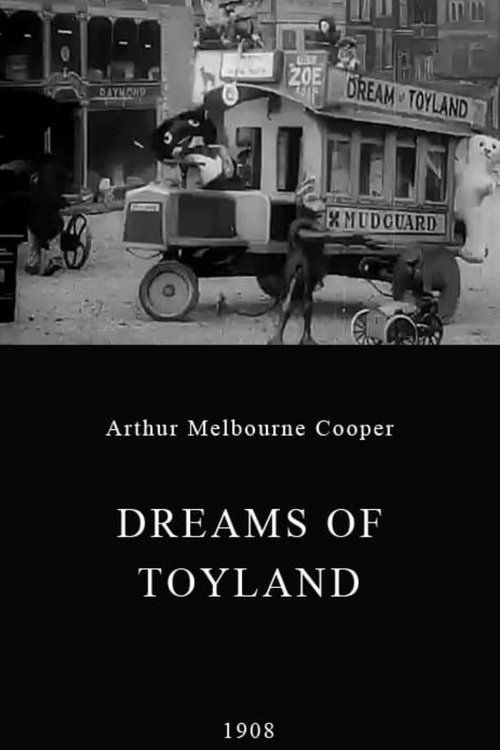

Dreams of Toyland

Plot

Dreams of Toyland follows a young boy who falls asleep while playing with his toys, only to witness them magically come to life in his dreams. The toys animate through stop-motion techniques, marching, dancing, and creating their own miniature world of adventure and wonder. As the dream progresses, various toys including soldiers, dolls, and mechanical figures engage in playful scenarios that mirror a child's imagination running wild. The film culminates with the boy awakening, leaving viewers to question whether the magical events were merely a dream or a secret reality of toys when humans aren't watching.

Director

Arthur Melbourne CooperAbout the Production

Arthur Melbourne Cooper created this film using stop-motion animation techniques, which were highly innovative for 1908. The film was shot in Cooper's home studio where he meticulously moved toys frame by frame to create the illusion of movement. Cooper used his daughter's toys as props and reportedly worked with primitive equipment, including homemade camera rigs to achieve the necessary stability for stop-motion work.

Historical Background

Dreams of Toyland was created during a revolutionary period in cinema history when filmmakers were experimenting with the medium's possibilities. 1908 was just over a decade after the birth of cinema, and filmmakers worldwide were discovering new techniques including special effects, animation, and narrative storytelling. The Edwardian era in Britain saw a flourishing film industry with companies like British Gaumont producing hundreds of films annually. This period preceded World War I and reflected the optimism and technological progress of the early 20th century. The film emerged alongside other pioneering works in animation, including works by Émile Cohl and J. Stuart Blackton, contributing to the development of animation as an art form.

Why This Film Matters

Dreams of Toyland represents a crucial milestone in animation history, demonstrating early mastery of stop-motion techniques that would influence generations of animators. The film captures the universal childhood fantasy of toys coming to life, a theme that would become a staple in children's entertainment from Toy Story to Nutcracker adaptations. As one of the earliest British animated films, it showcases the UK's important role in early cinema development. The preservation of Edwardian toys and play patterns provides valuable historical documentation of childhood material culture from this period. The film's influence extends to modern stop-motion studios like Aardman Animations, which continues Britain's legacy in this animation technique.

Making Of

Arthur Melbourne Cooper was a photographer turned filmmaker who discovered animation through experimentation. He developed his stop-motion techniques by moving objects slightly between exposures, creating the illusion of movement. The production took place in Cooper's home studio in St Albans, where he built makeshift sets using household items and toys. Cooper worked with primitive equipment, often modifying cameras and creating his own animation rigs. The painstaking process required moving each toy by tiny increments, with some sequences taking days to complete just a few seconds of footage. Cooper's wife often assisted with the production, helping to move props and manage the complex setup required for each shot.

Visual Style

The cinematography in Dreams of Toyland employed primitive stop-motion techniques that were revolutionary for 1908. Cooper used single-frame exposure to create smooth movement of inanimate objects, a technique that required exceptional patience and precision. The camera work was static, typical of early cinema, with the animation happening within the frame rather than through camera movement. Lighting was basic but effective, using natural light or simple lamps to illuminate the miniature sets. The composition focused on creating clear, readable images that would allow audiences to appreciate the magical transformation of toys from static objects to animated characters.

Innovations

Dreams of Toyland pioneered stop-motion animation techniques using three-dimensional objects, predating more famous early works in the field. Cooper developed methods for maintaining consistent lighting and camera positioning between frames, crucial technical challenges in stop-motion work. The film demonstrated early understanding of animation principles including squash and stretch, timing, and weight, even in these primitive forms. Cooper's use of actual toys rather than specially designed models showed innovation in working with existing objects. The film's survival and preservation represent an achievement in itself, given the fragility of early film stock and the high loss rate of cinema from this period.

Music

As a silent film from 1908, Dreams of Toyland originally had no synchronized soundtrack. During theatrical exhibition, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra in larger theaters. The musical accompaniment would have been improvised or selected from standard pieces appropriate to the mood and action on screen. Modern screenings and restorations often feature period-appropriate musical scores to recreate the original viewing experience. Some contemporary versions have been scored with new compositions specifically designed to enhance the whimsical nature of the animation.

Memorable Scenes

- The sequence where toy soldiers march in formation across the miniature battlefield, demonstrating Cooper's precise control of multiple animated objects simultaneously

- The transformation scene where static toys suddenly begin moving, creating the magical moment that establishes the film's premise

- The dance sequence featuring dolls and other toys moving in coordinated patterns, showcasing early understanding of animation timing and rhythm

Did You Know?

- Dreams of Toyland is considered one of the earliest surviving examples of stop-motion animation in cinema history

- Arthur Melbourne Cooper pioneered the use of stop-motion with toys, predating more famous animators like Willis O'Brien

- The film was originally titled 'Toys' in some markets

- Cooper developed his animation techniques while working as a photographer and discovered stop-motion accidentally when his camera jammed

- The toys used in the film were actual children's toys from the Edwardian era, providing historical insight into period playthings

- British Film Institute has preserved this film as part of their collection of early British animation

- Cooper's daughter served as the child actor in some of his films, though it's unclear if she appeared in this specific production

- The film was created during the golden age of British cinema when the UK was producing more films than Hollywood

- Cooper's animation work influenced later pioneers including Ladislas Starevich and Wladyslaw Starewicz

- The film's survival is remarkable given that over 90% of silent films have been lost to history

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of Dreams of Toyland is difficult to document due to the limited film journalism of 1908, but trade publications of the era noted the film's technical innovation. Modern film historians and animation scholars recognize it as a groundbreaking work, with the British Film Institute highlighting its importance in the development of animation. Critics today praise Cooper's technical skill and artistic vision, considering the film remarkably sophisticated for its time. Animation historians often cite it as evidence that stop-motion techniques were developed earlier than previously believed, challenging traditional narratives about animation history.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th century audiences were reportedly fascinated by the magical quality of toys coming to life, as stop-motion animation was a novelty that seemed like genuine magic to viewers of 1908. Children and adults alike were amazed by the technique, which represented a significant advancement beyond the simple trick films of earlier cinema. The film's brief runtime and straightforward appeal made it popular in music halls and early cinema programs. Modern audiences viewing the film today often express surprise at the sophistication of the animation given its age, with many noting how well the basic techniques hold up more than a century later.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès' trick films

- Early photographic experiments with motion

- Victorian and Edwardian children's literature

- Magic lantern shows

- Stage magic and illusion performances

This Film Influenced

- The Little Pianist (1908)

- The Teddy Bears (1907)

- Willis O'Brien's early stop-motion work

- Ladislas Starevich's animated films

- Modern stop-motion features including Toy Story and Coraline

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved by the British Film Institute (BFI) in their National Archive. While not completely intact, sufficient footage survives to represent Cooper's work and the film's significance. The BFI has undertaken restoration work to stabilize and digitize the surviving elements. The preservation status is considered good for a film of this age, though some deterioration is inevitable given the material's age and the primitive nature of early film stock.