Duniya Na Mane

"A bold challenge to social injustice"

Plot

Duniya Na Mane tells the story of Nirmala, a young, educated girl who is forced into marriage with Seth Jamnadas, an elderly widower with grown children. Despite her protests and the significant age gap, the marriage is arranged by her uncle who stands to gain financially. Nirmala refuses to accept her fate and rebels against the patriarchal system, finding an unexpected ally in Jamnadas's youngest son, who is closer to her age. The film powerfully depicts her struggle for autonomy and dignity, challenging the regressive social norms that treat women as property. Through Nirmala's journey, the film exposes the hypocrisy of a society that claims to be modern while clinging to oppressive traditions like child marriage and age-disparate unions.

Director

About the Production

The film was produced during the golden era of Prabhat Film Company and was one of their most ambitious projects. Director V. Shantaram invested significant resources in ensuring the film's technical excellence and social impact. The production team conducted extensive research into the social issues depicted, consulting with social reformers of the time. The film's realistic approach to its subject matter was revolutionary for Indian cinema of the 1930s.

Historical Background

Duniya Na Mane was created during a pivotal period in Indian history when the country was under British rule and experiencing significant social reform movements. The 1930s saw growing awareness about women's rights, with organizations like the All India Women's Conference advocating for legal reforms including raising the marriage age for girls. The film emerged from this context of social awakening, reflecting the tensions between tradition and modernity. It was made just a decade after the Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929, which made child marriage illegal but was poorly enforced. The film's bold critique of patriarchal practices aligned with the broader nationalist movement's vision of a progressive, independent India. Cinema was becoming an important medium for social commentary, and Prabhat Film Company was at the forefront of using films for social reform.

Why This Film Matters

Duniya Na Mane holds immense cultural significance as a pioneering work of social cinema in India. It was one of the first films to directly challenge regressive social practices and present a female protagonist who actively resists oppression. The film's portrayal of a young woman asserting her right to choose her own partner was revolutionary for its time and set a precedent for future feminist cinema in India. It contributed to public discourse about women's rights and helped normalize conversations about social reform. The film's success proved that audiences were ready for content that addressed real social issues, encouraging filmmakers to tackle controversial subjects. Its impact extended beyond entertainment, becoming part of the broader movement for women's emancipation in India. The film continues to be studied in film schools as an exemplary work of socially relevant cinema.

Making Of

The making of Duniya Na Mane was a revolutionary process that challenged conventional filmmaking practices of the time. Director V. Shantaram was deeply committed to social reform and used cinema as a medium for change. He assembled a team of like-minded artists who shared his vision. The casting process was meticulous, with Shanta Apte being chosen for her ability to portray both vulnerability and strength. The film was shot using innovative camera techniques, including close-ups that emphasized the emotional turmoil of the characters. The production faced resistance from conservative elements who opposed the film's progressive message, but Shantaram remained steadfast in his commitment to telling this important story. The music recording was particularly challenging, as the film required songs that could convey both traditional values and modern sensibilities.

Visual Style

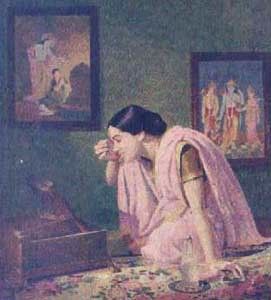

The cinematography of Duniya Na Mane was groundbreaking for its time, employing techniques that enhanced the film's emotional impact and social message. Cinematographer V. Avadhoot used innovative camera angles to emphasize the power dynamics between characters, often shooting from below to show Nirmala's defiance and from above to depict the oppressive nature of the patriarchal system. The film made effective use of close-ups to capture the subtle emotions of the characters, particularly Nirmala's inner turmoil and determination. Lighting was used symbolically, with Nirmala often shown in soft, natural light while the older husband was frequently depicted in harsh shadows. The film also incorporated tracking shots that created a sense of movement and progress, reflecting the changing social landscape. The visual style combined realism with artistic expression, creating images that were both beautiful and meaningful.

Innovations

Duniya Na Mane was technically ahead of its time in several aspects. The film pioneered the use of synchronized sound in Indian cinema, with dialogue recording that was remarkably clear for the period. The editing techniques employed were sophisticated, using cross-cutting to build tension and parallel editing to contrast different characters' perspectives. The film's sound design was particularly noteworthy, using silence strategically to emphasize dramatic moments and employing ambient sounds to create a realistic atmosphere. The makeup and costume design were carefully researched to reflect the social status and personalities of the characters. The film also experimented with narrative structure, incorporating flashbacks and dream sequences that were innovative for Indian cinema of the 1930s. These technical achievements contributed significantly to the film's impact and demonstrated the growing sophistication of Indian filmmaking.

Music

The music of Duniya Na Mane was composed by Keshavrao Bhole, who was known for his ability to blend traditional Indian melodies with modern sensibilities. The soundtrack featured several songs that became popular for their meaningful lyrics and emotional depth. Shanta Apte, who played Nirmala, sang most of the songs herself, bringing authenticity and passion to the performances. The music served not just as entertainment but as a narrative device, advancing the story and revealing character motivations. Songs like 'Ab Ke Baras' and 'Jhoom Jhoom Ke' became anthems of women's empowerment. The soundtrack was notable for its avoidance of typical filmi music conventions, instead opting for a more classical and refined approach that matched the film's serious tone. The background score was equally innovative, using minimal instrumentation to create tension and emphasize key dramatic moments.

Famous Quotes

Main ek jawan ladki hoon, ek budhe ke saath shaadi nahi kar sakti - I am a young woman, I cannot marry an old man

Shiksha hamara haq hai, koi nahi cheen sakta - Education is our right, no one can take it away

Zindagi jeene ke liye jeeni chahiye, bas sehni nahi - Life must be lived, not just endured

Badlav ki shururat ek hi se hoti hai - Change begins with one person

Purane rivaz badalne honge, warna hum badal jaayenge - Old customs must change, or we will change

Memorable Scenes

- The confrontation scene where Nirmala refuses to accept the marriage proposal, standing up to the entire family with courage and dignity

- The emotional breakdown scene where Nirmala confides in the youngest son about her fears and dreams

- The courtroom sequence where Nirmala argues for her right to choose her own life partner

- The final scene where Nirmala walks away from the oppressive household, symbolizing her emancipation

- The scene where Nirmala teaches the children, showing how education can be a tool for change

Did You Know?

- The film was based on a Marathi novel 'Na Patnari Goshta' written by Shri. N.V. Kulkarni

- It was also released in Hindi as 'Duniya Na Mane' and in Marathi as 'Kunku'

- The film was one of the earliest Indian films to receive international recognition

- It was screened at the Venice International Film Festival, a rare achievement for Indian cinema in the 1930s

- The film's lead actress, Shanta Apte, was known for her powerful singing voice and sang several songs in the film

- Director V. Shantaram considered this one of his most important socially relevant works

- The film was banned in several princely states due to its controversial subject matter

- It was one of the first Indian films to directly address the issue of age disparity in marriages

- The film's success led to increased awareness about the problem of child marriage in India

- The character of Nirmala became an icon of women's empowerment in Indian cinema

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics hailed Duniya Na Mane as a groundbreaking work that transcended the conventions of commercial cinema. Reviews praised its courage in addressing taboo subjects and its sophisticated treatment of complex social issues. Critics particularly lauded Shanta Apte's performance as Nirmala, describing it as powerful and nuanced. The film's technical aspects, including its cinematography and sound design, were also commended for their innovative approach. International critics at the Venice Film Festival recognized its artistic merit and social importance. Modern critics continue to regard the film as a milestone in Indian cinema history, often citing it as an early example of feminist filmmaking. The film is frequently included in lists of the most important Indian films ever made, with particular appreciation for its lasting relevance and artistic integrity.

What Audiences Thought

Duniya Na Mane was received with enthusiasm by audiences who were hungry for meaningful cinema that reflected their social realities. The film resonated particularly with urban, educated viewers who were grappling with similar conflicts between tradition and modernity in their own lives. Many women viewers found inspiration in Nirmala's character and her refusal to accept her fate passively. The film's success at the box office demonstrated that socially relevant content could be commercially viable. However, it also faced opposition from conservative sections of society who found its message too radical. Despite some controversy, the film developed a loyal following and became a talking point in social circles. Its impact was such that it continued to be discussed and referenced long after its theatrical run, contributing to ongoing conversations about women's rights and social reform in India.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Film Award at the Venice International Film Festival (1937)

- Special Jury Mention for its social significance

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Social reform movements of 1930s India

- Women's rights activism

- Indian nationalist movement

- Progressive literature of the period

- International cinema dealing with social issues

This Film Influenced

- Pinjra (1972)

- Nadiya Ke Paar (1948)

- Jagte Raho (1956)

- Mother India (1957)

- Bandini (1963)

- Mirch Masala (1987)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been partially preserved by the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) in Pune. While some portions have suffered from the natural degradation of nitrate film stock, significant portions remain intact. The Film Heritage Foundation has undertaken restoration efforts, and a restored version was screened at various film festivals. The original negatives are believed to be lost, but good quality prints exist in archives. The film is considered part of India's cinematic heritage and ongoing efforts are being made to preserve it for future generations.