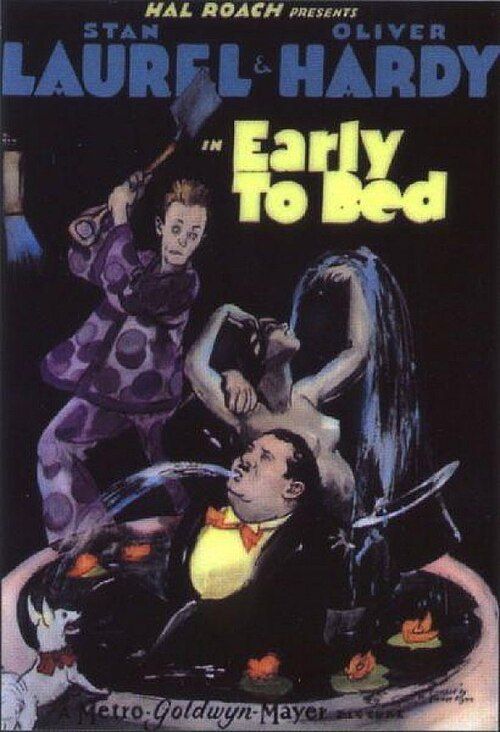

Early to Bed

Plot

In this silent comedy classic, Oliver Hardy unexpectedly inherits a large fortune and moves into a luxurious mansion. Deciding he needs proper domestic help, he hires his old friend Stan Laurel as his butler, but immediately begins tormenting him with impossible demands and cruel practical jokes. Stan endures the abuse with his characteristic patience until Oliver's mistreatment becomes unbearable, at which point Stan snaps and goes on a destructive rampage through the mansion. The comedy culminates in Stan systematically demolishing Oliver's expensive furnishings and possessions, turning the elegant household into complete chaos. The film ends with Oliver realizing his fortune has been literally destroyed by his mistreated servant, delivering a satisfying reversal of power dynamics.

Director

Cast

About the Production

This was one of the last silent films Laurel and Hardy made before transitioning to sound. The production utilized extensive prop destruction, requiring multiple takes of Stan's rampage scenes. The mansion set was built specifically for this film and was designed to be easily damaged and rebuilt for different takes. The film was shot during the period when Laurel and Hardy were establishing their classic character dynamic that would define their later sound films.

Historical Background

'Early to Bed' was produced in 1928, a watershed year in cinema history marking the end of the silent era and the beginning of the sound revolution. The Jazz Singer had been released in 1927, and studios were rapidly converting to sound production. Despite this technological upheaval, silent comedies continued to be produced and were still popular with audiences. Laurel and Hardy were at the peak of their silent film success, having recently established their enduring character dynamic. The film reflects the social dynamics of the late 1920s, including the fascination with sudden wealth (during the roaring twenties boom) and class tensions. The Great Depression was just around the corner, making the film's theme of wealth destruction particularly prescient. This period also saw the rise of the two-reel comedy format as a staple of movie theater programming.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the last great Laurel and Hardy silent comedies, 'Early to Bed' represents the culmination of their visual comedy style before the transition to sound. The film exemplifies their mastery of physical comedy and character-based humor without relying on dialogue. It demonstrates how Laurel and Hardy developed their iconic dynamic of the pompous Hardy and the childlike Laurel, a formula that would serve them well in their subsequent sound films. The destruction sequence influenced countless later comedy films, establishing the cathartic appeal of seeing an oppressor get their comeuppance through physical chaos. The film also represents the end of an era in comedy, as the art of silent comedy reached its final evolution before being largely replaced by verbal humor in the sound era. Today, it stands as an important document of the transition period in American comedy cinema.

Making Of

The production of 'Early to Bed' took place during a pivotal moment in cinema history as the industry was transitioning from silent to sound films. Director Emmett J. Flynn, primarily known for dramatic features, brought a more polished visual style to this comedy than typical Laurel and Hardy shorts. The destruction sequence required careful choreography and multiple camera setups to capture the escalating chaos. Stan Laurel, who was increasingly involved in the creative development of their films, helped refine the gags to maximize their physical comedy impact. The mansion set was constructed with breakaway furniture and props specifically designed to create spectacular destruction while ensuring the safety of the performers. The film was shot quickly, as was typical for comedy shorts of the era, with most scenes completed in one or two takes to maintain freshness and spontaneity in the performances.

Visual Style

The cinematography by George Stevens employs the clear, bright lighting typical of late 1920s comedy shorts, ensuring maximum visibility for the physical gags. The camera work is functional rather than artistic, focusing on capturing the performers' actions clearly. Wide shots are used effectively during the destruction sequence to show the scale of the chaos, while medium shots capture the performers' reactions. The mansion set is photographed to emphasize its opulence before the destruction, making the subsequent damage more impactful. Stevens uses relatively static camera positions, which was standard for comedy filming of the era, allowing the performers to control the frame and timing of their gags. The film demonstrates the transition from the more static camerawork of early silent films to the slightly more mobile approach that would become common in the early sound era.

Innovations

While 'Early to Bed' doesn't feature groundbreaking technical innovations, it demonstrates the refinement of comedy filmmaking techniques by the late silent era. The film showcases sophisticated prop design and breakaway furniture technology that allowed for repeated takes of the destruction sequence. The editing rhythm during the rampage scenes is particularly effective, building momentum through increasingly rapid cuts. The production design of the mansion set represents the high level of craftsmanship achieved by Hal Roach Studios by 1928. The film also demonstrates the mastery of timing and pacing that had been developed in comedy shorts throughout the 1920s. The coordination required for the complex destruction sequence shows the advanced planning and execution capabilities of studio comedy units by this period.

Music

As a silent film, 'Early to Bed' would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters during its original release. The typical score would have included popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and specially composed mood music to enhance the comedy. The destruction sequence would have been accompanied by frantic, percussive music to heighten the chaos. Modern releases of the film have featured newly composed scores by silent film accompanists, often using piano or small ensemble arrangements. These contemporary scores typically draw from 1920s popular music styles while incorporating comedic musical motifs that underscore the physical action. The absence of dialogue means the visual comedy must carry the entire narrative, making the musical accompaniment crucial for establishing mood and rhythm.

Famous Quotes

(Intertitle) 'Congratulations, Mr. Hardy! You have inherited a fortune!'

(Intertitle) 'Stan, you're hired as my butler!'

(Intertitle) 'This is going to be fun!'

(Intertitle) 'I've had enough!'

Memorable Scenes

- The extended destruction sequence where Stan systematically demolishes Oliver's mansion, starting with small acts of defiance and escalating to complete chaos, breaking furniture, smashing vases, and tearing down curtains in a cathartic rampage that represents the film's comic climax

Did You Know?

- This film was released just months before the debut of their first sound film 'Unaccustomed As We Are' (1929)

- The mansion set was so elaborate that it took several days to construct and was completely destroyed during filming

- Stan Laurel performed many of his own stunts during the destruction sequence, including breaking furniture and smashing props

- The film showcases an early example of the 'revenge' plot device that would become a recurring theme in Laurel and Hardy's work

- Oliver Hardy's weight gain for his character was becoming more pronounced by this point, establishing his iconic appearance

- The title 'Early to Bed' is ironic as the film contains no reference to the saying 'Early to bed, early to rise'

- This was one of the few Laurel and Hardy films directed by Emmett J. Flynn, who typically directed dramatic features

- The film's destruction sequence was so popular that elements were reused in later comedy films by other studios

- A surviving print was discovered in the 1970s in a private collection, helping preserve this important work

- The intertitles were written by H.M. Walker, who wrote many of the classic Laurel and Hardy title cards

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews praised the film for its inventive gags and the chemistry between Laurel and Hardy. The Motion Picture News noted 'the team's usual excellent timing and the spectacular finale provides plenty of laughs.' Modern critics have recognized 'Early to Bed' as one of the stronger Laurel and Hardy silent shorts, with particular appreciation for the escalating destruction sequence. Film historian William K. Everson called it 'a fine example of the team's silent work, showing their complete mastery of visual comedy.' The film is often cited in retrospectives of Laurel and Hardy's career as representing their silent comedy at its most refined. Critics have noted how the film's structure anticipates their later sound work, with the careful build-up of frustration leading to explosive release.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1928 responded enthusiastically to 'Early to Bed,' particularly enjoying the cathartic destruction sequence where Stan finally gets revenge on Oliver. The film was popular enough to warrant wide distribution through the Hal Roach network. Modern audiences discovering the film through revival screenings and home media have found it holds up well, with the physical comedy transcending the silent format. Laurel and Hardy fans consider it an essential entry in their filmography, often praising it as one of their most satisfying revenge comedies. The film's straightforward premise and escalating chaos make it accessible even to viewers unfamiliar with silent comedy conventions. Contemporary audience reactions on classic film platforms consistently rate it among the better Laurel and Hardy shorts.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier master-servant comedies

- Mack Sennett slapstick traditions

- Charlie Chaplin's class commentary films

- Harold Lloyd's escalation comedy

This Film Influenced

- Later Laurel and Hardy revenge comedies

- The Three Stooges destruction shorts

- Abbott and Costello servant comedies

- Modern physical comedy destruction sequences

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in complete form and has been preserved by major film archives. A 35mm print exists in the Library of Congress collection. The film has been restored for DVD and Blu-ray releases as part of Laurel and Hardy collections. The visual quality is generally good for a film of its age, though some wear is evident in existing prints. The film is not considered lost or partially lost, unlike many silent comedies from the same period.