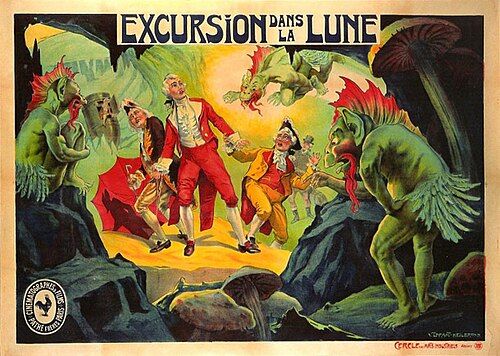

Excursion to the Moon

Plot

In this whimsical remake of Méliès' classic, a group of astronomers gather at their observatory and enthusiastically decide to build a rocket ship for a journey to the moon. After constructing their bullet-like spacecraft with great theatricality, they launch themselves into space in a spectacular sequence of special effects. Upon landing on the lunar surface, they encounter bizarre moon inhabitants and experience fantastical adventures in the moon's strange environment. The astronomers face various challenges and wonders before eventually making their dramatic return to Earth, where they are celebrated as heroes for their extraordinary celestial voyage.

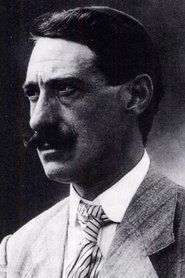

Director

About the Production

Segundo de Chomón created this as a direct response to Georges Méliès' 'A Trip to the Moon' (1902), using Pathé's superior resources and his own technical innovations. The film featured more sophisticated special effects than Méliès' original, including multiple exposures and hand-tinted coloring throughout. De Chomón was known for his meticulous attention to detail and often improved upon techniques pioneered by other filmmakers.

Historical Background

1908 was a pivotal year in early cinema, marking the transition from simple actualities and trick films to more elaborate narrative productions. The film industry was becoming increasingly commercialized, with major companies like Pathé establishing global distribution networks. This period saw intense competition between French studios, particularly between Pathé and Méliès' Star Film company. The scientific discoveries of the late 19th century, including advances in astronomy and the early space race concepts, captured public imagination and made space-themed films popular. Cinema was also transitioning from fairground attractions to more respectable theatrical entertainment, with films becoming longer and more sophisticated. De Chomón's work represented the technical maturation of cinema, moving beyond simple tricks to complex visual storytelling.

Why This Film Matters

Excursion to the Moon represents an important moment in early cinema history, demonstrating the rapid evolution of film technology and storytelling techniques. It exemplifies the competitive nature of early French cinema and how filmmakers built upon each other's innovations. The film contributed to establishing science fiction as a viable genre in cinema, showing that audiences were hungry for fantastical stories about exploration and discovery. It also highlights the international nature of early cinema, with a Spanish director working in France creating content for global distribution. The film's success helped establish the template for space travel films that would influence cinema for decades. It represents a key example of how early filmmakers used cinema to visualize humanity's dreams of space exploration, predating actual space travel by over half a century.

Making Of

Segundo de Chomón created this film while working as Pathé's primary special effects director. He was given significant resources to produce a film that could compete with Méliès' international success. The production involved elaborate stage sets constructed at Pathé's studio in Vincennes, with de Chomón personally supervising the complex special effects sequences. The filming required multiple exposures and careful matte work to create the illusion of space travel and lunar landscapes. De Chomón's wife, Julienne Mathieu, likely participated in the production, as she was a regular collaborator. The entire production would have taken several weeks, an unusually long time for films of this period, reflecting the complexity of the effects and the importance Pathé placed on competing with Méliès.

Visual Style

The film employed sophisticated multiple exposure techniques to create the illusion of space travel and supernatural events. De Chomón utilized careful matte photography to composite different elements, creating seamless transitions between reality and fantasy. The camera work was static, as was typical of the era, but the compositions were carefully designed to maximize the theatrical effects. The film made extensive use of the stencil coloring process (Pathécolor), which allowed for more precise and vibrant colors than Méliès' hand-coloring techniques. The lighting was carefully manipulated to create dramatic shadows and highlights, enhancing the otherworldly atmosphere of the lunar sequences.

Innovations

The film showcased several technical innovations for its time, including advanced multiple exposure techniques that allowed for more complex visual effects than Méliès' original. De Chomón employed sophisticated matte photography and substitution splices to create smooth transitions between scenes. The stencil coloring process used by Pathé allowed for more consistent and detailed color application than manual methods. The film also featured more elaborate mechanical props and sets than were typical for the period. The special effects sequences demonstrated an understanding of perspective and scale that was advanced for 1908. These technical achievements helped establish new standards for visual effects in early cinema.

Music

Like all films of this period, Excursion to the Moon was originally silent. When screened in theaters, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance, typically a pianist or small orchestra. The music would have been selected to match the mood of each scene - dramatic for the launch, whimsical for the lunar adventures, and triumphant for the return. Some theaters may have used popular classical pieces or specially composed music. The exact musical accompaniment would have varied by venue and was not standardized as part of the film itself.

Famous Quotes

No recorded dialogue - silent film with intertitles that would have varied by country of distribution

Memorable Scenes

- The rocket launch sequence with smoke and fire effects

- The landing on the moon with the rocket embedded in the lunar surface

- The encounter with the moon's strange inhabitants

- The return journey with Earth growing larger in the distance

- The final celebration scene on Earth with the heroic astronomers

Did You Know?

- Segundo de Chomón was often called 'The Spanish Méliès' due to his similar fantastical style and technical prowess

- This film was part of Pathé's strategy to compete directly with Méliès' Star Film company

- De Chomón used a stencil coloring process that was more advanced than Méliès' hand-coloring techniques

- The film featured more elaborate sets and props than Méliès' original version

- De Chomón was married to actress Julienne Mathieu, who appeared in many of his films

- Pathé distributed this film internationally, helping establish de Chomón's reputation beyond France

- The rocket design was slightly different from Méliès' version, showing de Chomón's artistic interpretation

- This was one of many 'remakes' or homages de Chomón created of other filmmakers' successful works

- The film's success led to de Chomón becoming Pathé's chief special effects expert

- Unlike many films of the era, multiple copies survived due to Pathé's extensive distribution network

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's technical sophistication and visual splendor, often noting that it surpassed Méliès' original in technical execution. Trade publications of the era highlighted Pathé's superior production values and de Chomón's innovative effects work. Modern film historians view the film as a significant example of early special effects cinema, though often noting its derivative nature in relation to Méliès' work. Critics today appreciate it as a showcase of de Chomón's technical prowess and as an important document of early cinematic competition and innovation. The film is frequently studied in film history courses as an example of how early filmmakers developed and refined cinematic techniques.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1908 responded enthusiastically to the film's spectacular visuals and imaginative story. The film was a commercial success for Pathé, playing to packed houses in Europe and America. Viewers were particularly impressed by the elaborate special effects and the hand-colored sequences, which added to the film's magical quality. The familiar story structure, based on the popular Méliès film, made it immediately accessible to audiences who were already familiar with space travel fantasies. The film's success demonstrated that audiences had an appetite for increasingly sophisticated visual effects and longer narrative films. Contemporary audience reactions were recorded in trade papers as being full of wonder and excitement at the cinematic possibilities on display.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- A Trip to the Moon (1902) by Georges Méliès

- Jules Verne's novels (From the Earth to the Moon)

- H.G. Wells' The First Men in the Moon

- Contemporary astronomical discoveries

- Stage magic traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later space travel films

- The Great Train Robbery (technical influence)

- Subsequent Pathé fantasy productions

- Early animated films (through visual effects techniques)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in several film archives worldwide, including the Cinémathèque Française and the Library of Congress. Multiple copies survive in various states of completeness, some with the original stencil coloring intact. The film has been digitally restored by several institutions and is available on various home video compilations of early cinema.