Fantasmagorie

"Le premier film de dessin animé du monde"

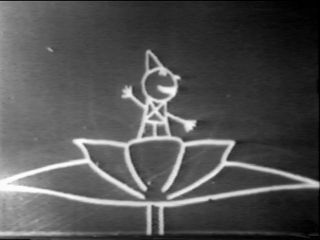

Plot

Fantasmagorie follows a stick figure character who undergoes a series of surreal transformations throughout the film. The protagonist materializes a movie theatre from his body, encounters an elephant that transforms into various shapes, finds himself imprisoned only to escape through magical transformations. The narrative flows as a stream-of-consciousness dream sequence where objects and characters continuously morph into one another, defying physical laws and logical progression. The film culminates with the character transforming into a gentleman who tips his hat to the audience before disappearing, creating a self-referential loop that breaks the fourth wall.

Director

About the Production

Cohl created this film using traditional animation techniques, drawing each frame on paper and then shooting them sequentially. The film was created by drawing on paper, then shooting each frame, creating what we now recognize as traditional animation. The distinctive chalk-like appearance was achieved by drawing each frame on paper and then inverting the negative to create the white-on-black effect. The entire film consists of approximately 700 hand-drawn frames.

Historical Background

Fantasmagorie was created during the early cinema boom of the late 1900s, when filmmakers were experimenting with the possibilities of the new medium. 1908 was a pivotal year in cinema, with Georges Méliès still creating his fantastical films and the Lumière brothers continuing to document reality. The film emerged from Paris's vibrant avant-garde art scene, where movements like the Incoherents challenged conventional artistic expression. This period saw the birth of animation as a distinct cinematic art form, moving beyond simple optical toys like the zoetrope to full-fledged narrative films. The industrial revolution had made film equipment more accessible, allowing artists like Cohl to experiment with the medium. France was the world's leading film producer at this time, with companies like Gaumont and Pathé dominating global cinema.

Why This Film Matters

Fantasmagorie represents the birth of animation as an art form and established many techniques that would become standard in the industry. Its influence extends beyond animation to surrealism and abstract art movements of the early 20th century. The film demonstrated that animation could create worlds impossible in live-action, opening new creative possibilities for storytellers. It established the principle of metamorphosis as a fundamental animation technique, later used by artists like Walt Disney and Norman McLaren. The film's stream-of-consciousness narrative influenced experimental filmmakers and avant-garde animators throughout the 20th century. It also demonstrated that animation could be a vehicle for adult artistic expression, not just children's entertainment. The preservation and study of Fantasmagorie has been crucial for understanding the origins of animation as both a technical and artistic medium.

Making Of

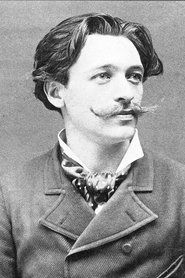

Émile Cohl, originally a political caricaturist and member of the avant-garde Incoherents movement, brought his surreal artistic sensibility to animation. He created Fantasmagorie by drawing each frame on paper with black ink, then photographing the drawings one by one. The process was laborious and time-consuming, requiring precise registration of each drawing to maintain smooth motion. Cohl's background in caricature influenced the fluid, morphing quality of the animation, where faces and shapes transform seamlessly. The film was produced at Gaumont's studio in Paris, where Cohl had access to the necessary equipment. His experience with the Incoherents, an artistic movement that embraced absurdity and rejected conventional artistic standards, directly informed the film's dreamlike, nonsensical narrative structure.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Fantasmagorie was groundbreaking for its use of frame-by-frame photography to create the illusion of movement. Cohl employed a stop-motion technique applied to drawings rather than objects, essentially inventing traditional animation. The black-and-white cinematography creates a distinctive chalk-on-blackboard effect through the use of negative photography. The camera work was static, as the focus was on the animated drawings themselves, but the compositions were carefully planned to maximize the impact of the transformations. The film's visual style was influenced by the aesthetic of magic lantern shows, with their ghostly, floating images. The cinematography emphasized contrast and silhouette, making the morphing shapes more dramatic and readable to the audience.

Innovations

Fantasmagorie pioneered the fundamental technique of traditional animation: drawing each frame individually and photographing them sequentially to create movement. Cohl developed registration techniques to ensure smooth transitions between frames, a challenge that animators continue to perfect today. The film demonstrated the power of metamorphosis as an animation principle, showing how one image could fluidly transform into another. Cohl's use of negative photography to create the distinctive white-on-black appearance was innovative for the time. The film established the concept of the animated short as a complete narrative form, rather than just a novelty act. It also demonstrated that animation could tell abstract, non-linear stories, expanding the narrative possibilities of the medium.

Music

Fantasmagorie was originally released as a silent film, as synchronized sound technology would not be developed until the late 1920s. In contemporary theatrical presentations, the film would have been accompanied by live musical accompaniment, typically a pianist or small orchestra performing popular tunes of the era or improvised music to match the on-screen action. Modern restorations and presentations often feature newly composed scores, with musicians creating period-appropriate music using instruments common in 1908. Some contemporary screenings feature experimental scores that emphasize the film's surreal and abstract qualities. The lack of synchronized sound actually enhances the film's dreamlike quality, allowing the visual transformations to exist in their own timeless space.

Famous Quotes

While the film contains no dialogue, its visual language speaks volumes: the transformation of a simple stick figure into countless forms became the visual vocabulary of animation itself.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where a stick figure emerges from the hands of the animator, establishing the self-referential nature of the work

- The elephant transformation sequence where the creature morphs into various shapes, showcasing the limitless possibilities of animation

- The prison escape scene where the character transforms to slip through bars, demonstrating animation's ability to defy physical laws

- The final scene where the character becomes a gentleman and tips his hat to the audience, breaking the fourth wall

Did You Know?

- Considered the first fully animated film in cinema history

- The title 'Fantasmagorie' refers to a type of 19th-century magic lantern show that featured ghostly projections

- Cohl was inspired by J. Stuart Blackton's 'Humorous Phases of Funny Faces' (1906) but expanded the concept considerably

- The film's distinctive visual style came from drawing on paper and then inverting the negative during processing

- Each frame was drawn individually, making it one of the earliest examples of traditional hand-drawn animation

- The stick figure protagonist was likely based on the 'Little Man' character popular in French comic strips of the time

- Cohl created the film while working for Gaumont, where he was initially hired as a writer and caricaturist

- The film was released without sound, as synchronized sound technology wouldn't exist for another two decades

- The transformation sequence where the character becomes an elephant references the popularity of circus imagery in early 20th century France

- Cohl was 51 years old when he created this groundbreaking film, making him one of animation's oldest pioneers

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics in 1908 were amazed by the film's magical qualities, with French newspapers describing it as 'a drawing that comes to life' and 'pure cinema magic'. Critics noted how the film seemed to defy the laws of nature through its continuous transformations. Modern film historians universally recognize Fantasmagorie as a milestone in cinema history, with the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress considering it for preservation. Animation historians consider it the first true animated film, predating other early works by several months. Critics have praised its innovative use of metamorphosis and its surreal, dreamlike quality that anticipated later artistic movements. The film is frequently cited in academic studies of early cinema and animation history as a foundational work that established many of animation's core principles.

What Audiences Thought

Early 1908 audiences were reportedly astonished and delighted by Fantasmagorie, with many viewers believing they were witnessing actual magic rather than a carefully crafted illusion. The film's short length and whimsical nature made it popular as part of variety-style film programs common in early cinemas. Contemporary accounts suggest audiences would applaud and laugh at the various transformations, particularly the sequence involving the elephant. The film's popularity helped establish animation as a viable commercial format, leading Gaumont to produce more animated shorts. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives and film festivals continue to be charmed by its primitive yet sophisticated animation techniques. The film remains popular in animation history courses and museum exhibitions, where viewers appreciate its historical significance and artistic innovation.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- J. Stuart Blackton's 'Humorous Phases of Funny Faces' (1906)

- The Incoherents art movement

- Magic lantern shows and phantasmagoria performances

- Georges Méliès's trick films

- Political caricature and cartoon art

- Circus and vaudeville entertainment

This Film Influenced

- Winsor McCay's 'Gertie the Dinosaur' (1914)

- Walt Disney's early 'Laugh-O-Grams'

- Oskar Fischinger's abstract animations

- Norman McLaren's experimental films

- The surreal animations of the 1920s and 1930s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Fantasmagorie has been preserved and restored by various film archives, including the Cinémathèque Française. While the original nitrate print has deteriorated, high-quality copies exist in several film archives worldwide. The film is part of the permanent collection of major film institutions and has been digitally restored for modern viewing. Its preservation status is considered good, with multiple copies ensuring its survival for future generations.