Five Minutes of Pure Cinema

Plot

Five Minutes of Pure Cinema is an experimental avant-garde short film that abandons traditional narrative structure in favor of exploring the fundamental elements of cinematic art. The film consists of rapidly edited visual sequences focusing on abstract forms, geometric patterns, and rhythmic movements that create a purely visual experience. Chomette employs various cinematic techniques including superimposition, rapid cutting, and visual contrasts to demonstrate the medium's capacity for creating meaning through imagery alone. The work progresses through different visual motifs, from architectural elements to natural forms, all arranged to create a visual symphony that emphasizes the unique properties of film as an art form. This pioneering work represents an early attempt to define cinema as an independent artistic medium, separate from theater or literature.

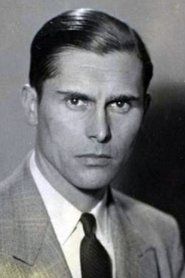

Director

About the Production

Created during the height of the French avant-garde movement, this film was part of Chomette's exploration of 'cinéma pur' (pure cinema). The production utilized experimental techniques that were groundbreaking for 1926, including rapid montage sequences and abstract visual compositions. Chomette, influenced by contemporary artistic movements, deliberately avoided narrative elements to focus on the visual and rhythmic qualities unique to cinema. The film was likely shot on 35mm film using available light and simple camera setups, emphasizing the director's belief that cinema's power lay in its visual and temporal properties rather than complex production values.

Historical Background

Five Minutes of Pure Cinema was created during a remarkable period of artistic experimentation in post-World War I France. The 1920s saw Paris emerge as the global center of avant-garde art, with movements like Dadaism, Surrealism, and Purism influencing all artistic disciplines. In cinema, this era witnessed the emergence of the French Impressionist movement and the subsequent push toward even more radical experimentation. The film reflects the broader cultural questioning of traditional art forms that characterized the period, as artists sought to break free from established conventions and explore new modes of expression. The technological developments of the 1920s, including more portable cameras and faster film stock, enabled filmmakers like Chomette to experiment with new techniques. This work also emerged alongside significant developments in other art forms - Stravinsky's revolutionary musical compositions, the abstract paintings of Mondrian and Kandinsky, and the architectural innovations of Le Corbusier - all of which shared a similar interest in breaking down traditional forms to their essential elements.

Why This Film Matters

Five Minutes of Pure Cinema represents a crucial moment in the development of film as an independent art form, challenging the prevailing notion that cinema was merely a commercial entertainment medium or a vehicle for literary adaptation. The film's radical approach to visual storytelling influenced generations of experimental filmmakers and helped establish the vocabulary of abstract cinema. Its emphasis on pure visual elements prefigured later developments in music videos, commercials, and contemporary digital art that rely on visual rhythm and abstract composition. The work also contributed to the theoretical discourse about cinema's unique properties, influencing film theorists who argued for the medium's autonomy. In the broader cultural context, the film exemplifies the 1920s avant-garde's determination to create new artistic languages appropriate to the modern era, rejecting traditional narrative structures in favor of forms that reflected the fragmented, accelerated experience of modern life. Today, the film is studied in film schools as an early example of pure cinema and continues to inspire artists working in visual media.

Making Of

The creation of Five Minutes of Pure Cinema emerged from Henri Chomette's deep involvement with the Parisian avant-garde art scene of the 1920s. Chomette, working alongside experimental filmmakers like Germaine Dulac and Jean Epstein, sought to establish cinema as an independent art form with its own unique language. The production process was highly experimental, with Chomette often shooting footage without a clear plan, allowing the editing process to determine the final structure. He worked with basic camera equipment, proving that artistic innovation didn't require substantial resources. The film's rapid editing style was revolutionary for 1926, requiring Chomette to develop new techniques for splicing and arranging footage to create rhythmic visual patterns. Unlike commercial productions of the era, this film had no script, no professional actors, and no studio backing - it was truly an independent artistic statement created with minimal resources but maximum artistic ambition.

Visual Style

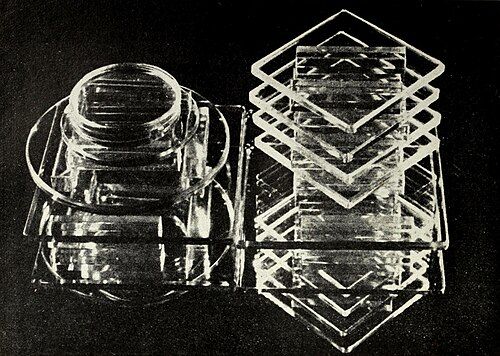

The cinematography of Five Minutes of Pure Cinema is characterized by its experimental approach to visual composition and its emphasis on abstract forms and patterns. Chomette employed innovative techniques for the period, including extreme close-ups, unusual camera angles, and rapid movements to create visual rhythms. The film utilizes high contrast lighting to emphasize geometric shapes and textures, creating stark black and white compositions that highlight the two-dimensional nature of the cinematic image. Chomette experimented with focus and depth of field to create abstract visual effects, sometimes shooting through prisms or using reflective surfaces to distort reality. The cinematography deliberately avoids conventional establishing shots or traditional composition rules, instead creating visual sequences that function like musical phrases. The camera work emphasizes movement and transformation, with many sequences showing the gradual metamorphosis of shapes and patterns. This approach to cinematography was revolutionary for 1926 and demonstrates Chomette's understanding of cinema's potential for creating purely visual experiences.

Innovations

Five Minutes of Pure Cinema achieved several technical innovations for its time, particularly in the realm of editing and visual composition. Chomette's use of rapid montage was groundbreaking for 1926, with some sequences featuring cuts that were much faster than typical commercial films of the era. The film demonstrated early examples of what would later become known as rhythmic editing, with visual patterns timed to create a sense of musicality without actual sound. Chomette also experimented with superimposition and multiple exposure techniques to create layered visual effects that were technically challenging with the equipment available in the 1920s. The film's abstract compositions required innovative approaches to lighting and camera placement, often using unconventional angles and movements to transform ordinary subjects into abstract patterns. While not technically complex in terms of production values, the film represented an achievement in pushing the boundaries of existing cinematic techniques to serve artistic rather than commercial purposes. These technical innovations influenced later developments in experimental cinema and even found their way into mainstream filmmaking as directors adopted more dynamic editing styles.

Music

As a silent film from 1926, Five Minutes of Pure Cinema was originally presented without a synchronized soundtrack. However, like many avant-garde films of the era, it would have been accompanied by live musical performances during its exhibition. The choice of musical accompaniment was crucial to the film's reception, with avant-garde venues often selecting contemporary classical compositions or improvised music that complemented the film's abstract visual rhythms. Some screenings may have featured works by modernist composers like Stravinsky or members of Les Six, whose musical innovations paralleled the film's visual experimentation. The lack of a fixed soundtrack allowed for different interpretations at each screening, with the musical accompaniment significantly influencing viewers' experience of the film's visual rhythms. Modern restorations and screenings of the film typically feature specially composed scores or carefully selected contemporary music that reflects the work's avant-garde nature. The absence of dialogue or sound effects emphasizes the film's focus on pure visual elements, making it a true example of silent cinema's artistic potential.

Famous Quotes

Cinema must become its own art, independent of theater and literature

The camera eye sees what the human eye cannot

Visual rhythm is the soul of cinema

We must free cinema from the tyranny of narrative

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence of rapidly edited geometric patterns that establishes the film's abstract visual language

- The middle section featuring superimposed architectural elements creating dreamlike compositions

- The finale where visual elements accelerate to create a climax of pure visual rhythm

Did You Know?

- Henri Chomette was the brother of more famous filmmaker René Clair, but chose to pursue experimental cinema rather than commercial filmmaking

- The film is considered one of the earliest examples of 'cinéma pur' or pure cinema movement

- Chomette coined the term 'cinégraphie' to describe his approach to visual rhythm in film

- The film was created during the same period as other notable avant-garde works like Ballet Mécanique (1924) and Un Chien Andalou (1929)

- Only fragments of many of Chomette's works survive today, making this complete 5-minute piece particularly valuable

- The film influenced later experimental filmmakers including Maya Deren and Stan Brakhage

- Chomette believed cinema should be 'a visual music' and this film was his manifesto of that principle

- The work was screened primarily in avant-garde circles and artistic salons in Paris rather than commercial theaters

- Chomette later abandoned filmmaking to focus on photography, believing the still image could better capture his artistic vision

- The film's emphasis on pure visual elements pre-dated and influenced similar movements in abstract film across Europe

What Critics Said

Upon its release in 1926, Five Minutes of Pure Cinema received attention primarily within avant-garde circles, with critics associated with experimental art publications praising its radical approach to cinematic form. French film critics of the era, particularly those writing for publications like Cinéa-Ciné pour tous and L'Art cinématographique, recognized Chomette's contribution to the cinéma pur movement, though mainstream critics often dismissed such experimental works as self-indulgent. Contemporary film historians and scholars have reevaluated the work's significance, viewing it as an important precursor to later developments in experimental cinema. Modern critics appreciate the film's pioneering role in establishing cinema's visual language independent of narrative constraints. The work is now frequently cited in academic studies of avant-garde cinema and is recognized for its influence on subsequent generations of experimental filmmakers. While not as well-known as some other experimental works of the period, it is regarded by film scholars as an essential document of the French avant-garde movement.

What Audiences Thought

The original audience for Five Minutes of Pure Cinema was limited to the small but dedicated community of avant-garde art enthusiasts in Paris during the 1920s. These viewers, accustomed to experimental works across various artistic disciplines, generally received the film with interest and appreciation for its innovative approach to cinematic form. However, the work was not intended for or seen by mainstream audiences, who at the time preferred narrative films with clear storylines. The film's abstract nature and lack of conventional narrative elements would have been challenging for general audiences of the era. In subsequent decades, as experimental cinema gained broader acceptance, the film found new audiences among film students, experimental filmmakers, and art cinema enthusiasts. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives or academic settings tend to appreciate it for its historical significance and its role in the development of cinematic language, though its abstract nature continues to make it more accessible to viewers with an interest in avant-garde art rather than those seeking traditional entertainment.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Ballet Mécanique (1924) by Fernand Léger

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

- Works of Dziga Vertov

- French Impressionist cinema

- Dadaist art

- Cubist painting

- Futurist manifestos

This Film Influenced

- Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) by Maya Deren

- Mothlight (1963) by Stan Brakhage

- Window Water Baby Moving (1959) by Stan Brakhage

- Various abstract films of the 1940s-1960s

- Music videos of the 1980s

- Digital abstract cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with some degradation typical of nitrate film from the 1920s. Archives such as the Cinémathèque Française hold copies, though the condition varies. Some restoration work has been undertaken, but complete restoration remains challenging due to the film's age and experimental nature. The film is considered at-risk but not lost.