Hamlet

Plot

Prince Hamlet of Denmark returns home from university to find his father dead and his mother remarried to his uncle Claudius. The ghost of Hamlet's father appears, revealing he was murdered by Claudius and demanding revenge. Hamlet feigns madness while plotting to expose his uncle's guilt, staging a play that reenacts the murder. His actions lead to political intrigue, accidental deaths, and ultimately a tragic conclusion where most main characters die, including Hamlet himself, leaving Denmark's throne to the invading Norwegian prince Fortinbras.

About the Production

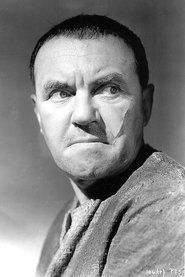

This was one of the earliest feature-length Shakespeare adaptations and captured the renowned stage actor Johnston Forbes-Robertson, who was considered one of the greatest Hamlet interpreters of his generation. The film was produced during a period when British cinema was beginning to establish itself artistically. Forbes-Robertson was 60 years old at the time of filming, bringing decades of theatrical experience to the role.

Historical Background

The year 1913 was a pivotal moment in world history and cinema. It was the eve of World War I, which would dramatically alter European society and the film industry. British cinema was experiencing a period of artistic growth, with producers beginning to see the potential for adapting literary works to the screen. The film industry was transitioning from short novelty films to longer, more ambitious productions. The Victorian era's emphasis on Shakespeare as cultural capital was still strong, making adaptations of his plays both commercially and culturally viable. The technology of cinema was still relatively primitive, with cameras being hand-cranked and lighting being rudimentary. This period also saw the beginning of the feature film as the dominant form of cinema, moving away from the one-reel shorts that had characterized early cinema.

Why This Film Matters

This 1913 adaptation of Hamlet holds significant cultural importance as one of the earliest attempts to preserve Shakespearean performance on film. It represents the transition from stage to screen and captures the acting style of the 19th-century theatrical tradition at a time when it was beginning to fade. The film demonstrates how early cinema sought cultural legitimacy by adapting prestigious literary works. Forbes-Robertson's performance is particularly valuable as it preserves the interpretation of one of the most celebrated Hamlets of the Victorian era. The film also illustrates the challenges of adapting complex, dialogue-heavy plays to the silent medium, requiring creative solutions through visual storytelling and intertitles. As an early British feature, it contributes to our understanding of the UK's film industry before it was overshadowed by Hollywood's dominance after World War I.

Making Of

The production of this 1913 Hamlet represents a significant moment in early cinema history, bridging the gap between Victorian theatrical tradition and the emerging medium of film. Director Hay Plumb was a prolific director in the British silent film era, making numerous short films and features. The casting of Johnston Forbes-Robertson was particularly significant, as he brought authentic theatrical gravitas to the production. The filming process would have been challenging, as early cinema equipment was bulky and required bright lighting. Actors accustomed to stage projection had to adapt their performances for the intimate camera lens. The production likely followed the common practice of the time, shooting scenes out of sequence and using minimal sets. The film would have been shot on nitrate stock, which was highly flammable and prone to deterioration, explaining why many copies of early films no longer exist.

Visual Style

The cinematography of this 1913 production would have utilized the techniques common to early British cinema. The camera was likely static for most scenes, with minimal movement due to the bulky equipment of the era. Lighting would have been rudimentary, primarily using natural light from studio windows or early artificial lighting. The film would have been shot on black and white film stock, with the visual storytelling relying on composition and gesture rather than camera movement. Close-ups were beginning to be used more frequently by 1913, but medium and long shots would have dominated the framing. The cinematography would have served primarily to record the performances rather than create visual poetry, reflecting the transitional nature of early cinema between theatrical recording and cinematic art.

Innovations

The technical achievements of the 1913 Hamlet were modest by modern standards but significant for their time. The production represented an early attempt to adapt a complex, full-length play to the cinema, requiring innovative approaches to narrative compression and visual storytelling. The use of intertitles to convey Shakespeare's dialogue was a technical necessity that became an art form in itself. The film likely utilized multiple camera setups and editing techniques that were advanced for 1913. The preservation of a complete theatrical performance on film was itself a technical achievement, capturing the nuances of Forbes-Robertson's interpretation for posterity. The production would have employed the latest film stock and camera equipment available in Britain in 1913, representing the technical capabilities of the British film industry before World War I.

Music

As a silent film, the 1913 Hamlet would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibition. Theaters typically employed pianists or small orchestras to provide musical accompaniment, often using classical pieces or specially compiled scores. For a Shakespeare adaptation, the music would likely have been more sophisticated than for typical comedies or action films of the period. The accompaniment might have included selections from classical composers or original compositions designed to enhance the dramatic mood. Large urban theaters might have had full orchestras, while smaller venues would have used a single piano or organ. The music would have been synchronized with the action on screen, with specific themes for characters and emotional cues for dramatic moments.

Famous Quotes

"To be, or not to be: that is the question"

"Something is rotten in the state of Denmark"

"Neither a borrower nor a lender be"

"This above all: to thine own self be true"

"Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio"

"The rest is silence"

"Frailty, thy name is woman"

"Get thee to a nunnery"

"There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so"

"When sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions"

Memorable Scenes

- The ghost scene on the battlements of Elsinore, where Hamlet confronts his father's spirit and learns of the murder

- The 'To be or not to be' soliloquy, where Hamlet contemplates suicide and the nature of existence

- The play within a play scene, where Hamlet stages 'The Mousetrap' to catch Claudius's guilt

- The graveyard scene with Yorick's skull, where Hamlet reflects on mortality

- The final duel scene, where the tragedy reaches its bloody conclusion

Did You Know?

- Johnston Forbes-Robertson was one of the most celebrated Shakespearean actors of the Victorian era and had famously played Hamlet on stage opposite Ellen Terry.

- This film represents one of the earliest attempts to capture a major Shakespearean performance on film, preserving the acting style of 19th-century theatrical tradition.

- The film was produced by the British & Colonial Kinematograph Company, which was one of Britain's most important early film production companies.

- Forbes-Robertson retired from the stage in 1913, the same year this film was made, making it potentially a record of his final interpretation of the role.

- The film was released just before World War I, during a golden period for British cinema that would be disrupted by the war.

- Silent Shakespeare films of this era often used intertitles extensively to convey the dialogue, as the plays were too dialogue-heavy to be told purely visually.

- Early cinema audiences were often familiar with Shakespeare's plays, allowing filmmakers to assume audience knowledge of the plots.

- The film's survival status is uncertain, as many early British films were lost due to the unstable nitrate film stock used at the time.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of the 1913 Hamlet is difficult to trace due to the limited survival of early film reviews and trade papers. However, films featuring renowned theatrical actors like Forbes-Robertson were generally received with interest by critics of the time, who saw them as elevating the cultural status of cinema. Reviews likely focused on the novelty of seeing a famous stage performance captured on film and the technical achievements of adapting Shakespeare to the silent medium. Modern critics and film historians view the film primarily as a historical document, valuable for its preservation of period performance styles and early cinema techniques. The film is studied today more for its historical significance than its artistic merits, as filmmaking techniques have evolved dramatically since 1913.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception of the 1913 Hamlet would have been influenced by the cultural prestige of both Shakespeare and Johnston Forbes-Robertson. Edwardian audiences were generally well-educated in Shakespeare's works, allowing them to follow the story despite the limitations of silent film. The presence of a famous stage actor likely drew theater-goers to cinemas, helping to bridge the cultural gap between legitimate theater and the still-emerging medium of film. Audiences of the time were accustomed to the more presentational acting style captured in the film, which would seem exaggerated to modern viewers. The film's success would have been measured by its ability to attract middle-class audiences who might otherwise have avoided cinema, helping to establish film as a respectable form of entertainment.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- William Shakespeare's original play

- Previous stage productions of Hamlet

- Victorian theatrical traditions

- 19th-century acting techniques

- Earlier silent Shakespeare adaptations

This Film Influenced

- Later Hamlet film adaptations

- Other Shakespeare adaptations of the silent era

- British literary adaptations of the 1910s-1920s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of the 1913 Hamlet is uncertain, with many sources suggesting it may be a lost film. Like many British films of this era, it was likely shot on unstable nitrate film stock that was prone to deterioration and fire. The British Film Institute's archive does not list a complete surviving copy, though fragments or still photographs may exist. The loss of this film is particularly unfortunate as it represents a rare opportunity to see Johnston Forbes-Robertson's acclaimed interpretation of Hamlet. Some film historians continue to search for surviving copies in private collections or archives worldwide, as films once thought lost have occasionally been rediscovered.