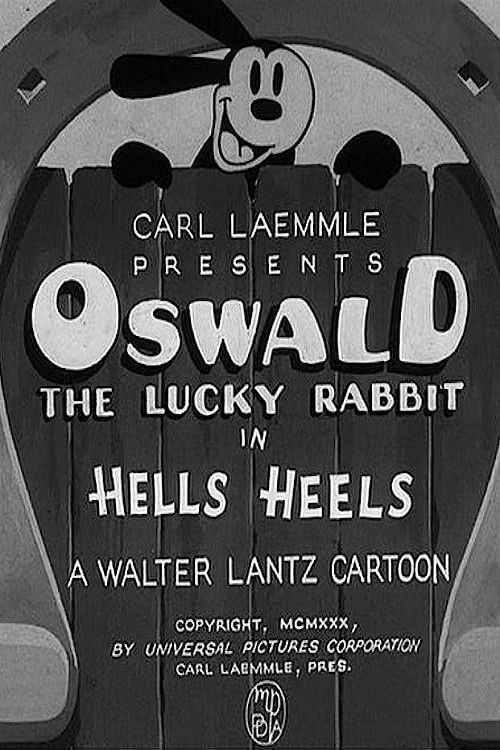

Hells Heels

"The Lucky Rabbit in a Wild West Riot!"

Plot

In this animated Western satire, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit is a reluctant outlaw forced by two hardened desperadoes—a dog with an eye patch and a peg-legged canine—to rob the bank in Heela City. After a chaotic explosion that reduces his accomplices to living skeletons, Oswald attempts to crack the bank's safe, only to find the local bulldog sheriff hiding inside. The sheriff promptly chases the rabbit out of town and into the harsh desert, where Oswald's luck takes a turn when he discovers a crying infant abandoned in the wilderness. Upon realizing the baby is actually the sheriff's own son, Oswald is compelled by the infant's surprisingly gruff and forceful personality to return to town and face the law. The short concludes with a series of slapstick encounters as Oswald tries to reunite the child with his father while avoiding the sheriff's wrath.

Director

About the Production

Hells Heels was the 20th Oswald the Lucky Rabbit short produced during the Walter Lantz era and the 72nd overall in the series. It was assigned production number 5194. This period was marked by a high-volume output, with the Lantz studio producing approximately 24 shorts in 1930 alone. The animation was handled by a team of future industry legends, including Bill Nolan and Manuel Moreno, who were tasked with maintaining the character's popularity after Universal took the rights from Walt Disney. The short is notable for its use of cycled animation and flat character designs, which were common cost-saving measures for the studio at the time.

Historical Background

Released in 1930, Hells Heels arrived during the 'talkie' revolution when studios were scrambling to add synchronized sound to their cartoons. The Great Depression was beginning to take hold, and audiences sought escapism in the form of slapstick comedy and Western parodies. This film represents the early 'Lantz Era' of Oswald, where the character was being repositioned to compete with Disney's rising star, Mickey Mouse. It also reflects the industry's shift toward parodying popular live-action features of the day, a trend that would later be perfected by Warner Bros.

Why This Film Matters

Hells Heels is significant as a bridge between the silent era and the Golden Age of animation. It showcases the evolution of 'personality animation,' where a character's traits are defined by their reactions to moral dilemmas—in this case, Oswald's decision to save a baby despite being a fugitive. The short also highlights the early use of synchronized sound gags, such as the talking safe and the musical score, which were cutting-edge for 1930. Its preservation ensures that the work of the Lantz studio remains accessible to animation historians.

Making Of

The production of Hells Heels occurred during a transitional phase for the Oswald series. After Walt Disney lost the rights to the character to Charles Mintz, and subsequently Carl Laemmle of Universal took production in-house, Walter Lantz was hand-picked to lead the new animation department. Lantz reportedly sought Disney's blessing before continuing the series. The animation team, led by Bill Nolan, worked under intense pressure to deliver a new short every two weeks. This led to the 'rubber hose' style of animation seen in the film, where limbs move without joints, and characters frequently survive impossible physical trauma, such as the bank explosion that turns the villains into skeletons.

Visual Style

As a hand-drawn animated short, the 'cinematography' involves the use of layered cels and static backgrounds typical of the early 1930s. The visual style is characterized by the 'rubber hose' technique, where characters exhibit extreme elasticity. Notable visual sequences include the high-contrast desert scenes and the use of 'impact frames' during the bank explosion. The backgrounds are relatively simple, focusing the viewer's attention on the character movement and physical gags.

Innovations

The film is a notable example of early synchronized sound in animation, successfully integrating dialogue, sound effects, and a full musical score. It also features 'skeleton' animation that required detailed frame-by-frame drawing to maintain the characters' anatomical structure while they remained 'alive.' The restoration of the film involved cleaning the original nitrate prints to preserve the clarity of the black-and-white line work and the fidelity of the early optical audio track.

Music

The soundtrack features the first score for the series by James Dietrich. It utilizes a synchronized orchestral track that mimics the action on screen (a technique later known as 'Mickey Mousing'). The score includes Western-themed motifs and ends with the iconic 'Boop-Oop-a-Doop' vocal tag, which became the signature closing for the Lantz Oswald shorts. The voice work includes contributions from Pinto Colvig, who would later become the voice of Disney's Goofy.

Famous Quotes

Radio Voice: When the gong rings it will be exactly one minute past!

Baby (in a deep voice): My daddy is the sheriff!

Memorable Scenes

- The bank explosion scene where Oswald's two dog accomplices are instantly charred into walking, talking skeletons while Oswald remains dazed but unharmed.

- The 'Radio Safe' gag where Oswald tries to crack the safe but instead tunes into a radio broadcast.

- The ending sequence where the tough-talking baby forces the 'Lucky Rabbit' to carry him back across the desert to the sheriff.

Did You Know?

- The film is a direct parody of the 1929 Universal feature film 'Hell's Heroes', which was an early adaptation of the novel 'The Three Godfathers'.

- This is the first Oswald cartoon to feature the musical score of James Dietrich, who would become a regular composer for the series.

- It is the earliest Walter Lantz-produced Oswald cartoon to be fully restored for modern audiences.

- The short features the debut of the famous 'Boop-Oop-a-Doop' ending tune, which became a staple for the series.

- Some historical sources and film catalogs incorrectly list this cartoon under the title 'Nell's Yells', which is actually a 1939 Columbia cartoon.

- The voice of the infant in the film is surprisingly deep and gruff, a recurring gag in early sound animation.

- Oswald's design in this film still retains the 'black rabbit' look before his major redesign into a white rabbit in 1935.

- The film contains a 'radio' gag where turning the dial on a safe produces a time-signal broadcast instead of opening the lock.

What Critics Said

At the time of its release, trade publications like The Film Daily and The Moving Picture World praised the Oswald series for its 'clever drawing' and 'humorous situations.' Modern critics and animation historians, such as Jerry Beck, have noted that while the Lantz-era shorts sometimes lacked the polish of Disney's work, they possessed a frenetic, surreal energy. Some contemporary reviews point out the 'flat' cel aesthetics but acknowledge the film's historical value as a successful parody and an early sound-era survivor.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by 1930s audiences who were already familiar with the 'Three Godfathers' story. Oswald remained a popular 'A-list' cartoon star throughout the early 30s, and this short's blend of Western action and baby-related comedy was a crowd-pleasing formula. Today, it is a favorite among classic animation enthusiasts for its dark humor—specifically the skeleton gag—and its status as a restored classic.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Hell's Heroes (1929)

- The Three Godfathers (Novel by Peter B. Kyne)

- Felix the Cat (Visual Style)

This Film Influenced

- Mickey's Nightmare (1932)

- 3 Godfathers (1948)

- The Three Godfathers (1936)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved and has been professionally restored. It is currently held in the Universal Pictures archive and was included in the 'Woody Woodpecker and Friends Classic Cartoon Collection' DVD set.