How a Mosquito Operates

Plot

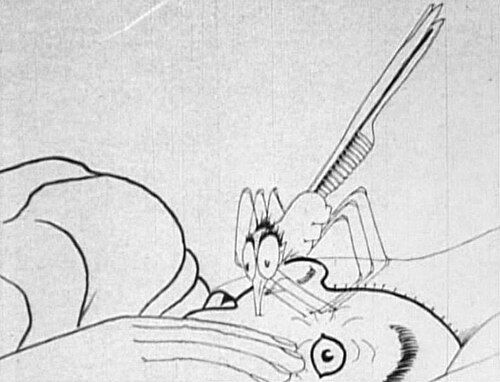

A hungry mosquito spots a man walking home and follows him to his bedroom. After the man falls asleep, the mosquito attempts to feed on his blood, but its first attempts startle the man awake. The mosquito proves incredibly persistent, repeatedly trying different approaches to get its meal while the sleeping man swats and struggles. The mosquito eventually succeeds in drinking so much blood that it becomes grotesquely swollen and unable to fly, ultimately exploding when the man finally crushes it against the wall.

Director

About the Production

Winsor McCay drew each of the approximately 6,000 drawings on rice paper, then photographed them one by one. The mosquito character was designed with articulated joints to allow for more natural movement. McCay used a new technique of keyframe animation, drawing main poses first then filling in the in-between frames. The film was created as part of McCay's vaudeville act, where he would appear on stage with the film.

Historical Background

In 1912, animation was in its infancy, with most early animated films consisting of simple trick photography or basic line drawings. Winsor McCay, already famous as a newspaper cartoonist for his comic strips 'Little Nemo in Slumberland' and 'Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend', was pioneering what would become character animation. The film industry was transitioning from short novelty films to feature-length productions, and vaudeville was still a major entertainment venue. This period saw the rise of motion pictures as a dominant form of entertainment, with New York City serving as a major production center. McCay's work represented a significant step forward in the artistic possibilities of animation, moving beyond mere technical novelty to storytelling and character development.

Why This Film Matters

'How a Mosquito Operates' is considered a landmark in animation history for establishing character animation as an art form. The mosquito was one of the first animated characters to display personality, motivation, and emotional range. The film demonstrated that animation could be used for sophisticated storytelling and comedy, not just technical demonstrations. McCay's techniques influenced generations of animators, and his emphasis on detailed drawing and fluid movement set standards that would dominate animation for decades. The film's success helped establish animation as a viable commercial medium and paved the way for the animation industry that would emerge in the 1920s and 1930s. It remains studied in film schools as an example of early animation innovation and artistic achievement.

Making Of

Winsor McCay created this film while working as a newspaper cartoonist. He would work on his animation projects at night and on weekends. The production process was incredibly labor-intensive - McCay drew each frame on 6.5 x 8.5 inch rice paper sheets. He developed a registration system using pegs to ensure consistent positioning of the drawings. The mosquito character was given articulated joints and expressive features to convey personality. McCay's employer initially disapproved of his 'frivolous' animation work, but the success of his first film 'Little Nemo' and this follow-up changed their attitude. McCay would often perform live with the film, sometimes drawing on stage while the animation played, creating a multimedia experience that amazed vaudeville audiences.

Visual Style

The film utilized McCay's innovative approach to animation photography, using a custom-built animation stand and registration system to ensure smooth movement. Each drawing was photographed on 35mm film using consistent lighting and positioning. The mosquito was animated with particular attention to weight and momentum, creating believable movement that was revolutionary for the time. McCay employed techniques like smears and multiple exposures to enhance the illusion of motion. The black and white cinematography emphasized the contrast between the delicate mosquito and the solid human figure, creating visual drama despite the monochrome format.

Innovations

McCay pioneered keyframe animation techniques in this film, drawing major poses first then filling in between frames. He developed an early registration system using pegs to maintain consistency across thousands of drawings. The mosquito character featured articulated joints allowing for more naturalistic movement than previous animated figures. McCay's use of perspective and scale in the animation created depth and dimensionality rarely seen in early animation. The film's smooth frame rate and fluid motion represented a significant advance over the jerky movements typical of earlier animated works.

Music

The film was originally silent, as was standard for 1912 productions. When shown in theaters, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra. In vaudeville performances, McCay himself would sometimes provide narration or sound effects. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores, including jazz-influenced music that complements the film's comic tone. Some contemporary screenings feature ragtime music appropriate to the 1912 period.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, it contains no dialogue, but the mosquito's actions and the man's reactions create a wordless narrative of persistence and frustration

Memorable Scenes

- The mosquito inflating grotesquely as it drinks blood, becoming so swollen it can barely fly

- The mosquito's persistent attempts to approach the sleeping man, dodging swats and blankets

- The final explosive scene where the overfilled mosquito bursts when crushed against the wall

Did You Know?

- This was Winsor McCay's second animated film, following 'Little Nemo' (1911)

- The mosquito character was one of the first animated figures to have a distinct personality and motivations

- McCay drew approximately 6,000 individual drawings for this 6-minute film

- The film was originally titled 'The Story of a Mosquito'

- McCay claimed he could draw 25,000 drawings in a month for his animations

- The mosquito's design included hinged joints to create more realistic movement

- This film helped establish the concept of character animation as opposed to mere trick photography

- McCay performed live with the film in vaudeville shows, sometimes interacting with the projected mosquito

- The film's success convinced McCay's employer (the New York Herald) to allow him more time for animation projects

- The exploding mosquito scene was considered quite shocking and graphic for 1912 audiences

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics and audiences were amazed by the film's technical achievement and the lifelike quality of the mosquito's movements. The New York Dramatic Mirror praised it as 'a remarkable example of what can be done with moving pictures' and noted the mosquito's 'uncanny realism'. Modern critics recognize it as a groundbreaking work that established key principles of character animation. Film historian Donald Crafton has called it 'a masterpiece of early animation' and notes its influence on later Disney and Warner Bros. cartoons. The film is frequently cited in animation histories as a pivotal work that demonstrated animation's potential for sophisticated storytelling and character development.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1912 were reportedly astonished by the film, with many believing McCay had somehow filmed a real, trained insect. The mosquito's personality and the humor of its persistent attempts to feed on the sleeping man delighted viewers. When shown as part of McCay's vaudeville act, audiences often gasped at the mosquito's realistic movements and laughed at its comic struggles. The film was popular enough to be shown widely in theaters and continued to be screened for years after its initial release. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives and animation festivals continue to appreciate its technical innovation and timeless humor.

Awards & Recognition

- Selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1994

Film Connections

Influenced By

- McCay's newspaper comic strips 'Little Nemo in Slumberland' and 'Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend'

- Émile Cohl's early animated films

- J. Stuart Blackton's 'Humorous Phases of Funny Faces'

- Georges Méliès's trick films

This Film Influenced

- 'Gertie the Dinosaur' (1914) - McCay's next animated film

- Early Disney and Warner Bros. character cartoons

- Fleischer Studios' 'Out of the Inkwell' series

- Modern character animation techniques

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Preserved by the Library of Congress and selected for the National Film Registry in 1994. The film has been restored and is available in high-quality digital format. Multiple prints exist in film archives worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art and the UCLA Film & Television Archive.