Humorous Phases of Funny Faces

Plot

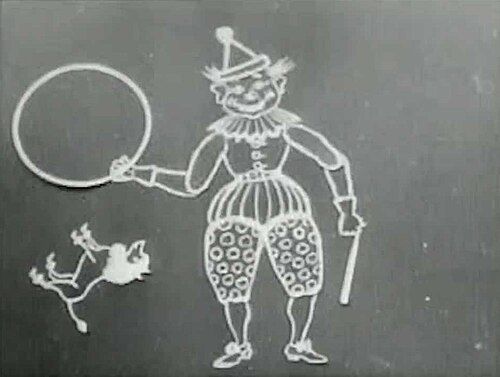

In this groundbreaking early animated film, a cartoonist (played by J. Stuart Blackton himself) stands before a large blackboard and begins drawing a series of faces and figures using chalk. Through the innovative use of stop-motion animation techniques, the drawn faces begin to move and transform independently of the artist's hand. The faces smile, frown, and change expressions, while a clown figure performs various antics. The cartoonist interacts with his animated creations, eventually erasing them and drawing new ones that continue to move and entertain. The film culminates with a gentleman figure who tips his hat to the audience, breaking the fourth wall in this early example of animated storytelling.

Director

Cast

About the Production

The film was created using a combination of live-action filming and stop-motion animation techniques. Blackton would draw a frame, film it, then slightly alter the drawing before filming the next frame. The chalkboard technique allowed for easy erasure and modification of the drawings between frames. The entire process was extremely labor-intensive, requiring hundreds of individual drawings for just a few minutes of animation.

Historical Background

The film was created during the pioneering era of cinema, just over a decade after the first motion pictures were invented. In 1906, the film industry was still in its infancy, with most productions being simple actualities or brief staged scenes. The nickelodeon boom was just beginning, and audiences were hungry for novel attractions. This period saw intense competition among early film studios like Edison's Biograph, Vitagraph, and others to create innovative content. Animation as an art form did not yet exist, making Blackton's work truly revolutionary. The film emerged from the tradition of magic lantern shows and vaudeville entertainment, where visual tricks and transformations were popular. The technical limitations of the time - hand-cranked cameras, nitrate film stock, and primitive editing equipment - make the sophistication of Blackton's animation even more remarkable.

Why This Film Matters

'Humorous Phases of Funny Faces' holds immense cultural significance as the birth of animation as an art form and industry. It demonstrated that drawings could be brought to life on screen, opening up entirely new possibilities for storytelling and entertainment. The film's success proved that audiences would accept and enjoy animated content, paving the way for the entire animation industry that would follow. It established fundamental principles of animation that would be refined by later pioneers like Winsor McCay, Walt Disney, and others. The film also represents an early example of breaking the fourth wall in cinema, with the animated character acknowledging the audience. Its influence extends beyond animation to visual effects, as the techniques Blackton developed would later be used in live-action films for magical transformations and special effects.

Making Of

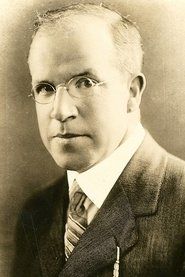

The creation of 'Humorous Phases of Funny Faces' involved a painstaking process that J. Stuart Blackton developed himself. Using a large blackboard as his canvas, Blackton would draw a figure or face with chalk, photograph it using a hand-cranked camera, then slightly alter the drawing before capturing the next frame. This stop-motion technique, combined with cut-out animation for some elements, created the illusion of movement. The live-action segments showing Blackton at work were filmed separately and integrated with the animated sequences. The entire production took several days to complete, which was unusually long for films of this period. Blackton's background as a cartoonist for the New York Evening World helped him understand the principles of movement and expression that he translated into this new medium of animation.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Humorous Phases of Funny Faces' was groundbreaking for its time, combining live-action filming with stop-motion animation. The camera work was static and straightforward, typical of early films, but the visual content was revolutionary. Blackton used a standard 35mm camera mounted on a tripod to capture both the live-action segments and the animated sequences. The chalkboard provided a high-contrast background that made the chalk drawings clearly visible on film. The lighting was natural and consistent, essential for maintaining the illusion of smooth animation between frames. Each animated movement was captured through individual photographs, creating a jerky but effective motion that audiences found magical and entertaining.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was the pioneering use of stop-motion animation, a technique Blackton essentially invented for this production. He developed a method of photographing sequential drawings to create the illusion of movement, establishing fundamental animation principles that would be used for decades. The chalkboard technique allowed for easy modification between frames, making the animation process more efficient than redrawing entire scenes. Blackton also successfully integrated live-action footage with animated sequences, creating a seamless blend that wouldn't become common until years later. The film demonstrated early understanding of timing, spacing, and squash-and-stretch principles that would later be formalized as animation fundamentals. These technical innovations laid the groundwork for the entire animation industry.

Music

As a silent film, 'Humorous Phases of Funny Faces' had no synchronized soundtrack. During its original theatrical run, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small theater orchestra. The musical accompaniment would have been improvised or chosen from standard silent film music libraries, matching the on-screen action with appropriate comedic or whimsical themes. Some theaters might have used sound effects created manually, such as bells or whistles, to enhance the animated sequences. The lack of dialogue meant the humor and storytelling had to rely entirely on visual expression, which Blackton accomplished through the exaggerated movements and expressions of his animated characters.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Blackton draws the first face and it begins to smile and move independently

- The clown character that performs acrobatic movements and tricks on the blackboard

- The transformation sequence where one face morphs into another through clever erasing and redrawing

- The final scene where the gentleman character tips his hat directly to the camera, breaking the fourth wall

Did You Know?

- This is widely considered the first animated film in history, predating other early animation works by several years.

- J. Stuart Blackton was a cartoonist and vaudeville performer before becoming a filmmaker, which influenced his innovative approach to animation.

- The film was originally titled just 'Funny Faces' but was later expanded to 'Humorous Phases of Funny Faces' for distribution.

- The animation technique used is often called 'chalkboard animation' or 'lightning animation' due to the way the drawings appear to move magically.

- Blackton created this film after being inspired by Thomas Edison's film 'The Enchanted Drawing' (1900), which used similar techniques.

- The film was shot on 35mm film at approximately 16 frames per second, the standard for silent films of the era.

- Vitagraph Studios, where this was made, was one of the most prolific American film studios of the early 1900s.

- The gentleman character who tips his hat at the end is believed to be a caricature of Blackton himself.

- The film's success led Blackton to create more animated works, including 'The Haunted Hotel' (1907).

- Only one complete print of the film is known to survive, preserved by the Library of Congress.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics and trade publications were amazed by the film's technical innovation. The Moving Picture World praised it as 'a most curious and entertaining exhibition of the possibilities of the motion picture art.' Variety noted that 'the drawings seem to move by some magical power, creating laughter and wonder in equal measure.' Modern critics recognize it as a foundational work in animation history. Film historian Donald Crafton has called it 'the first true animated film' and 'the ancestor of all subsequent animation.' The British Film Institute includes it in their list of the 100 most important American films, and it's frequently cited in animation studies as the starting point for the entire medium.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1906 were astonished and delighted by 'Humorous Phases of Funny Faces.' The film was a popular attraction in nickelodeons and vaudeville theaters, where it often played to packed houses. Viewers had never seen anything like drawings that moved independently of human hands, and many believed it was some form of magic or trick photography. The humor and charm of the animated characters resonated with audiences of all ages, making it one of the most successful Vitagraph releases of 1906. The film's popularity led to numerous imitations and inspired other filmmakers to experiment with animation techniques. Audience reactions were typically described as 'uproarious laughter' and 'widespread amazement' in contemporary theater reports.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Thomas Edison's 'The Enchanted Drawing' (1900)

- Magic lantern shows

- Vaudeville performance traditions

- Newspaper comic strips

- Chalk talk performances

This Film Influenced

- Winsor McCay's 'Gertie the Dinosaur' (1914)

- J. Stuart Blackton's 'The Haunted Hotel' (1907)

- Émile Cohl's 'Fantasmagorie' (1908)

- Walt Disney's early Laugh-O-Grams

- Fleischer Studios' Out of the Inkwell series

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved and available for viewing. A complete 35mm print is held by the Library of Congress as part of their paper print collection, which was a method of copyright registration in the early 1900s. The film has been digitally restored and is available through various archival institutions and online platforms. The preservation quality is remarkably good considering the film's age and the volatile nature of early nitrate film stock. Multiple archives worldwide hold copies, including the British Film Institute and the Museum of Modern Art's film department.