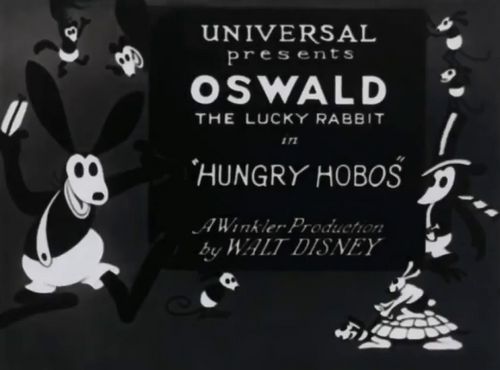

Hungry Hoboes

Plot

In this silent animated short, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and his perpetual antagonist Peg-Leg Pete are depicted as hobos riding the rails on a freight train. The story begins with the two rivals engaged in a game of checkers atop a moving boxcar, with their competitive spirit quickly escalating into slapstick chaos. When hunger strikes, their attention turns to finding food, leading to a series of comedic mishaps as they attempt to steal meals from various sources. The cartoon culminates in a frantic chase sequence where both characters' greed and rivalry result in them losing their stolen goods and ending up empty-handed. The film showcases the classic formula of rivalry-driven comedy that characterized many early Disney shorts.

Director

About the Production

This was one of the final Oswald cartoons produced by Disney before losing the character to Universal. The animation was created using traditional cel animation techniques with each frame hand-drawn and inked. The short featured the innovative use of rubber hose animation style, which gave characters fluid, elastic movements characteristic of the era. Disney's team used a multiplane camera setup for certain shots to create depth, though this technique was still in its early stages of development.

Historical Background

1928 was a pivotal year in American history and cinema. The nation was in the final years of the Roaring Twenties, a period of unprecedented prosperity and cultural change that would soon end with the 1929 stock market crash. In the film industry, 1928 marked the transition from silent films to 'talkies,' with Warner Bros.' 'The Jazz Singer' having revolutionized cinema the previous year. Animation was rapidly evolving from simple novelty acts to sophisticated storytelling medium. The Great Migration had changed American demographics, and hobo culture, while romanticized in entertainment, reflected real economic struggles for many. The Disney studio was still a small operation competing with larger animation studios like Fleischer Studios and Bray Productions. The year also saw significant technological advances in film equipment and techniques, with improvements in cameras, film stock, and projection technology. The rise of consumer culture and the growing importance of theatrical shorts as entertainment between features created opportunities for animation studios to reach wider audiences.

Why This Film Matters

'Hungry Hoboes' represents a crucial moment in animation history as one of the final works in Disney's Oswald the Lucky Rabbit series. The loss of Oswald to Universal was a devastating blow to Disney but ultimately catalyzed the creation of Mickey Mouse, who would become one of the most iconic characters in global popular culture. The film exemplifies the sophisticated character animation and storytelling that Disney was developing, techniques that would become hallmarks of the studio's later success. The hobo theme reflected broader American cultural themes of freedom, wanderlust, and economic struggle during the late 1920s. The cartoon's competitive dynamic between Oswald and Pete established character archetypes that would influence countless animated works. The technical innovations in this short, particularly in character movement and visual storytelling, contributed to the evolution of animation as an art form. The film's rediscovery in 2015 was significant for film preservationists and animation historians, providing insight into Disney's early development and the techniques that would define his studio's golden age.

Making Of

The production of 'Hungry Hoboes' took place during a tumultuous period in Walt Disney's career. Disney had created Oswald the Lucky Rabbit in 1927 at the request of producer Charles Mintz, who distributed the cartoons through Universal Pictures. The series was initially successful, with Disney producing 26 shorts between 1927 and 1928. However, behind the scenes, Disney was growing frustrated with the financial arrangements and lack of creative control. The animation team, including legends like Ub Iwerks and Les Clark, worked long hours at Disney's Hyperion Avenue studio in Los Angeles, pushing the boundaries of what was possible in animation. The rubber hose animation style used in this film gave characters a distinctive fluidity, with limbs that moved like rubber hoses without visible joints. This style was not only aesthetically pleasing but also easier to animate consistently across different artists. The production coincided with Disney's trip to New York in February 1928, where he discovered that Mintz had hired away most of his animators and planned to produce Oswald cartoons without him. This betrayal led Disney to abandon the character and create Mickey Mouse on the train ride back to California.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Hungry Hoboes' employed the standard techniques of late 1920s animation while pushing creative boundaries within those constraints. The film was shot on 35mm film using the standard frame rate of 16 frames per second for animation. The camera work included dynamic tracking shots following the moving train, creating a sense of motion and speed that was technically challenging for the period. The use of forced perspective in certain scenes gave depth to the otherwise two-dimensional animation. Lighting effects, while limited by the technology of the time, were used creatively to suggest different times of day and create atmosphere. The animation team employed subtle camera movements and zooms to focus on character reactions and physical comedy beats. The visual composition followed the principles of silent film cinematography, with careful attention to framing and visual storytelling. The black and white cinematography utilized contrast and shadow to enhance the dramatic and comedic elements of the story.

Innovations

The film showcased several technical achievements for its era, particularly in character animation and visual storytelling. The rubber hose animation technique used throughout the short represented a significant advancement in creating fluid, believable character movement. The animators achieved complex character interaction during the checkers game sequence, demonstrating sophisticated understanding of character dynamics and timing. The train sequences employed innovative perspective techniques to create the illusion of movement and depth. The animation team developed new methods for depicting weight and momentum, particularly in the physical comedy sequences. The film's use of continuity editing and shot composition showed a mature understanding of cinematic language applied to animation. The technical quality of the line work and consistency in character design across different animators' work represented an improvement in production standards. The background art, while simple, effectively established setting and mood through careful composition and detail. These technical innovations contributed to the evolution of animation from novelty to sophisticated art form.

Music

As a silent film, 'Hungry Hoboes' did not have an original synchronized soundtrack, but it would have been accompanied by live musical accompaniment during theatrical exhibitions. Typical theater organs or pianists would have performed popular songs of the era and classical pieces matched to the on-screen action. The musical selections likely included jaunty, upbeat tunes for the comedic sequences and more dramatic music for the chase scenes. The rhythm and tempo of the live music would have been crucial in enhancing the physical comedy and maintaining audience engagement. The lack of dialogue meant that music and sound effects (often created by theater musicians) were essential in conveying emotion and accentuating the visual gags. The musical accompaniment would have drawn from the standard repertoire of silent film theater music, with selections tailored to match the mood and pacing of each scene. The film's release in late 1928 meant it may have been shown in some theaters experimenting with early sound systems, though it was produced as a silent short.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue quotes available)

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Oswald and Peg-Leg Pete playing checkers on top of a moving train, demonstrating their competitive relationship through exaggerated physical comedy and clever visual gags

- The hunger-driven sequence where both characters attempt to steal food, resulting in a slapstick battle of wits and physical prowess

- The climactic chase scene where both characters' greed leads to them losing their stolen provisions, ending with them empty-handed and still hungry

Did You Know?

- This was one of the last 26 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit shorts produced by Walt Disney before he lost the character rights to Universal Pictures in 1928

- The film was considered lost for decades until a print was discovered in the United Kingdom's National Film Archive in 2015

- Oswald the Lucky Rabbit was Disney's first major animated star, created in 1927, predating Mickey Mouse by over a year

- Peg-Leg Pete would later become one of Disney's most enduring villains, eventually appearing in Mickey Mouse cartoons as simply 'Pete'

- The hobo theme was popular in 1920s entertainment, reflecting the economic hardships many Americans faced during the decade

- The checkers game sequence was particularly innovative for its time, showcasing complex character interaction and competitive dynamics

- Disney's loss of Oswald directly led to the creation of Mickey Mouse, as Disney needed a new character he owned outright

- The cartoon features no dialogue, relying entirely on visual storytelling and physical comedy, typical of silent era animation

- The train setting allowed for dynamic camera movements and perspective shots that were technically challenging for the period

- This short was released just months before the debut of 'Steamboat Willie', which would revolutionize animation with synchronized sound

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception for 'Hungry Hoboes' is difficult to trace due to the limited coverage of animated shorts in trade publications of the era. However, the Oswald series was generally well-received by exhibitors and audiences, with Variety and Moving Picture World noting the character's growing popularity. Critics of the time praised Disney's technical innovations and the increasingly sophisticated animation quality. Modern critics and animation historians have recognized the short as an important example of Disney's early work, with particular appreciation for its fluid animation and character dynamics. The film's rediscovery in 2015 generated significant excitement in the animation community, with scholars noting its importance in understanding Disney's artistic development. Animation historian Jerry Beck has highlighted the short as demonstrating Disney's mastery of silent comedy principles and his ability to create engaging character-driven narratives without dialogue. The technical quality of the animation, particularly in the movement sequences, has been praised as being ahead of its time.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to 'Hungry Hoboes' and other Oswald shorts was generally positive during their initial theatrical run. Moviegoers of the late 1920s had come to expect animated shorts as part of their theater experience, and Oswald had developed a substantial fan base. The character's mischievous personality and the cartoons' visual gags appealed to both children and adults. The hobo theme resonated with audiences familiar with train travel and the romanticized notion of the open road. Contemporary audience reactions are difficult to document precisely, but box office receipts for theaters showing Disney cartoons suggest strong attendance. Modern audiences have had limited opportunities to view the film due to its lost status for many years, but animation enthusiasts and Disney fans have shown great interest in its rediscovery. The cartoon's appeal today lies in its historical significance and its demonstration of early Disney animation techniques that would influence generations of animators.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Charlie Chaplin's tramp character

- Buster Keaton's physical comedy

- Harold Lloyd's daredevil sequences

- Felix the Cat cartoons

- Fleischer Studios' Out of the Inkwell series

- Vaudeville comedy routines

- Silent film chase sequences

- Contemporary comic strips

This Film Influenced

- Early Mickey Mouse cartoons

- Merrie Melodies and Looney Tunes shorts

- Tom and Jerry cartoons

- Popeye animated shorts

- Later Disney character rivalry cartoons

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Considered a lost film for decades until a 35mm nitrate print was discovered in the United Kingdom's National Film Archive in 2015. The film has since been preserved and restored by animation historians and preservationists. The discovered print, while showing signs of age and nitrate deterioration, was complete enough for full restoration. The restored version has been screened at film festivals and animation retrospectives, making it accessible to modern audiences for the first time in over 80 years. The preservation status is now considered stable, with digital copies maintained by animation archives and Disney's own preservation efforts.