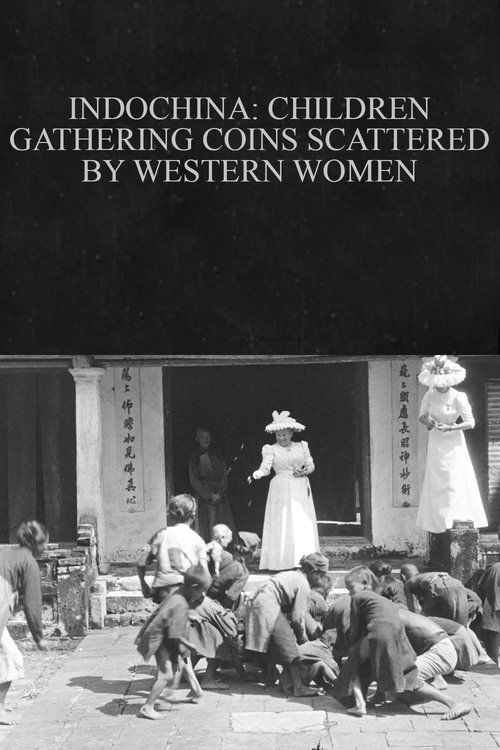

Indochina: Children Gathering Coins Scattered by Western Women

Plot

This early documentary short captures a staged scene in colonial Indochina where two elegantly dressed Western women stand on a balcony or elevated position, scattering coins to a crowd of Vietnamese children below. The children eagerly scramble and compete to collect the scattered money, creating a chaotic yet organized display of colonial power dynamics. The camera remains stationary, observing the entire interaction from a fixed position, typical of early Lumière-era actualités. The film serves as both a travelogue element and a visual record of the colonial relationship between Europeans and indigenous populations. The scene concludes as the women watch the children's enthusiastic coin-gathering, seemingly amused by the spectacle they have orchestrated.

Director

About the Production

Filmed by Gabriel Veyre, a Lumière company cinematographer sent to document exotic locations for European audiences. The scene was likely staged rather than captured spontaneously, as was common with early travelogue films. The use of real local children rather than actors adds an ethnographic quality to the production. The film was shot using the Lumière Cinématographe, which served as both camera and projector.

Historical Background

This film was created during the height of French colonial expansion in Southeast Asia, when Indochina (comprising modern Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) was under French control. The early 1900s saw tremendous European interest in exotic and 'primitive' cultures, fueled by colonial exhibitions, world fairs, and the new medium of cinema. The film reflects the paternalistic attitudes of the colonial era, presenting European superiority as natural and benevolent. Gabriel Veyre's work for the Lumière company was part of a broader effort to document and categorize the world through moving images, often reinforcing colonial hierarchies. The film emerged just a few years after the invention of cinema, when filmmakers were still exploring the possibilities of the new medium.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important early example of ethnographic cinema, despite its colonial perspective. It serves as a historical document of both early filmmaking techniques and colonial attitudes at the turn of the 20th century. The film is significant for being one of the earliest moving images captured in Indochina, providing visual documentation of the region during the colonial period. It exemplifies the 'exotic view' genre that dominated early documentary filmmaking and shaped Western perceptions of non-European cultures. The film also illustrates how cinema was used from its inception to reinforce and perpetuate colonial ideologies. Today, it is studied by film historians and postcolonial scholars as an example of how visual media constructed and maintained colonial power structures.

Making Of

Gabriel Veyre traveled extensively throughout Indochina with the cumbersome Cinématographe equipment, which had to be hand-cranked and required careful setup. The filming of this particular scene likely involved coordinating with local authorities or colonial administrators to gather the children. The Western women featured were probably wives of colonial officials or European expatriates living in Indochina at the time. The stationary camera position was typical of early Lumière productions, which favored observational perspectives over mobile cinematography. The coin-throwing action was repeated multiple times to ensure adequate footage, as film stock was expensive and early cameras had limited shooting capacity.

Visual Style

The film employs the characteristic static camera position of early Lumière productions, with the Cinématographe mounted on a tripod for stability. The composition places the Western women in an elevated position, literally and figuratively above the local children, reinforcing colonial hierarchies through visual arrangement. The black and white images show the technical limitations of early film stock, with limited tonal range and contrast. The single continuous take without editing was standard for the period, creating an unmediated observational quality. The framing captures both the action of coin-scattering and the reaction of the children, providing a complete view of the orchestrated scene.

Innovations

While not technically innovative for its time, the film demonstrates the portable capabilities of the Lumière Cinématographe, which allowed filming in remote locations like Indochina. The successful capture of a scene with multiple moving subjects in bright outdoor lighting showcases the adaptability of early film equipment. The film represents an early example of location shooting far from the filmmaker's home country, which was logistically challenging in 1901. The preservation of the film for over 120 years also speaks to the durability of early celluloid stock when properly stored.

Music

This was a silent film produced before the advent of synchronized sound. When originally exhibited, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a piano or small ensemble playing appropriate pieces. The musical accompaniment might have included exotic-sounding compositions or popular light classical pieces typical of the era. Some exhibitors may have used sound effects or had a lecturer provide narration explaining the scene to the audience. No original score was composed specifically for this film.

Memorable Scenes

- The entire film consists of a single memorable scene: Western women in elegant colonial dress standing above and scattering coins to Vietnamese children who scramble below to collect them, creating a visual metaphor for colonial relationships

Did You Know?

- Gabriel Veyre was one of the Lumière brothers' most prolific cinematographers, documenting locations across Asia and the Middle East

- The film is part of a series of 'exotic' views that were extremely popular with European audiences in the early 1900s

- The coin-scattering scene was a recurring motif in colonial films, symbolizing the relationship between colonizers and colonized

- This film survives today and is preserved in film archives, making it one of the earliest moving images of life in Indochina

- The children in the film were likely paid participants, though the amount probably exceeded what they could earn otherwise

- Western women in colonial settings were often depicted as benevolent figures in early cinema

- The film was originally shown as part of a program of short films, not as a standalone feature

- Veyre spent several years in Asia (1899-1901) documenting various locations for the Lumière company

- The film's French title was 'Indochine: Enfants ramassant des pièces jetées par des dames occidentales'

- Early actualités like this were often presented with live musical accompaniment and sometimes a lecturer explaining the scenes

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception of this film is not well-documented, as early shorts were rarely reviewed in the way feature films later would be. However, films like this were generally popular with European audiences who were fascinated by glimpses of exotic lands and peoples. Modern critics and film historians view the film through a postcolonial lens, recognizing it as both a valuable historical document and a problematic artifact of colonial ideology. The film is often cited in academic discussions of early documentary practices and the representation of non-Western cultures in cinema. While technically simple by modern standards, it is acknowledged for its role in the development of travelogue and ethnographic filmmaking.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th century European audiences reportedly found films like this fascinating, as they offered rare visual access to distant colonies and 'exotic' cultures. The novelty of seeing moving images of people from different parts of the world was a major draw in the cinema's first decade. Modern audiences viewing the film in archival contexts often experience a mix of historical interest and discomfort with the colonial power dynamics on display. The film is now primarily viewed by scholars, film enthusiasts, and those interested in colonial history rather than general entertainment audiences.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Lumière company actualités

- Early travelogue films

- Colonial exhibition photography

- Ethnographic documentation practices

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent colonial travelogues

- Early ethnographic films

- Documentaries about Southeast Asia

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Preserved - The film survives in archives and is part of various early cinema collections. It has been digitized and is available through some film archives and educational platforms.