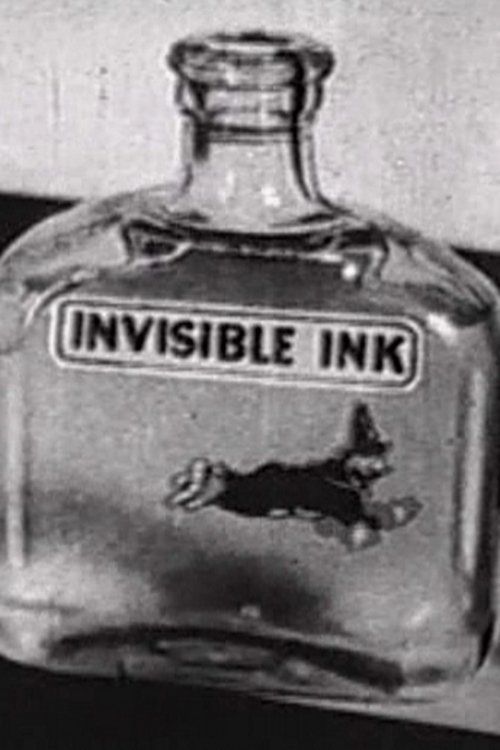

Invisible Ink

Plot

In this early Fleischer Studios animated short, an animator attempts to work at his drawing board but is continually interrupted by the mischievous Koko the Clown, who emerges from the inkwell. Frustrated by Koko's persistent antics, the animator devises various schemes to trap and contain the animated character. The cartoon showcases the meta-humor of animation itself, with the creator battling his own creation in a playful yet increasingly desperate struggle. The film culminates in a series of gags as Koko outsmarts the animator's attempts at capture, demonstrating the character's clever and rebellious nature.

Director

Cast

About the Production

This was part of the early 'Out of the Inkwell' series that pioneered the combination of live-action and animation. The film used the Rotoscope technique, invented by Max Fleischer, which involved tracing over live-action footage to create more realistic animation. The production was notably challenging due to the primitive animation equipment of the era and the labor-intensive frame-by-frame process.

Historical Background

1921 was a pivotal year in early animation, occurring just a few years after World War I when the film industry was rapidly expanding. The animation field was still in its infancy, with most cartoons being simple gag films lacking recurring characters. The Fleischer brothers were among the pioneers developing narrative animation with personality-driven characters. This period saw the transition from earlier 'lightning sketch' acts to more sophisticated animated shorts. The film industry was centered in New York before the eventual migration to Hollywood, and independent studios like Fleischer's were competing with larger producers. The technical limitations of the era meant that innovation was crucial, and films like 'Invisible Ink' represented significant steps forward in both technique and storytelling.

Why This Film Matters

'Invisible Ink' represents a crucial milestone in animation history as part of the series that established many conventions still used today. The concept of animated characters interacting with their real-world creators became a recurring trope that influenced countless later works. The film helped establish Koko the Clown as one of animation's first true stars, paving the way for character-driven animation. The meta-narrative approach influenced later works from Warner Bros.' 'Duck Amuck' to modern films like 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit.' The Fleischer Studios' unique visual style, combining surreal imagery with urban sensibility, helped distinguish American animation from its European counterparts and established New York as an early animation hub.

Making Of

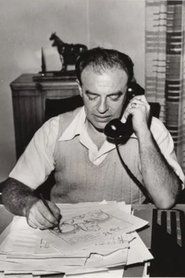

The production of 'Invisible Ink' took place in the early days of animation history when the Fleischer brothers, Max and Dave, were working out of a small apartment in New York. Max Fleischer would often perform the live-action segments himself, playing the frustrated animator. The animation process was incredibly laborious, with each frame drawn by hand on paper, then transferred to celluloid sheets. The Rotoscope device, which Max had invented, was used to trace over live-action footage to achieve more natural movement for Koko. The brothers often worked through the night to meet deadlines, with Dave handling the direction and timing while Max focused on the technical innovations and animation. The film's meta-narrative of the animator struggling with his creation mirrored the real challenges the Fleischers faced in bringing their animated characters to life.

Visual Style

The film employed a groundbreaking combination of live-action cinematography and animation techniques. The live-action segments were shot using standard cameras of the era, while the animated portions required precise alignment to create the illusion of interaction. The cinematography featured innovative use of matte shots to blend the two mediums seamlessly. The camera work was static by modern standards but included careful framing to accommodate the animated elements. The visual style emphasized the contrast between the realistic live-action world and the fluid, exaggerated animation of Koko. The film's visual vocabulary included jump cuts between reality and animation, creating a disorienting but entertaining effect that was revolutionary for its time.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was the pioneering use of the Rotoscope, Max Fleischer's patented invention that allowed for more realistic animation by tracing over live-action footage. The seamless integration of live-action and animation was groundbreaking for 1921, requiring innovative matte techniques and precise timing. The film demonstrated early mastery of perspective and depth in animation, with Koko appearing to exist in three-dimensional space. The production also showcased early examples of character animation with personality, moving beyond simple gag animations. The technical innovations in this film influenced animation techniques for decades and established many of the foundational principles of combining different media types.

Music

As a silent film from 1921, 'Invisible Ink' would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The typical score would have been provided by a theater's pianist or organist, who would improvise or use cue sheets provided by the studio. The music likely featured jaunty, comedic themes during Koko's appearances and more dramatic or frantic passages during the chase sequences. Some larger theaters might have had small orchestras accompany the film. The soundtrack would have included sound effects created live by musicians or theater staff, such as whistles, bangs, and other noises to enhance the comedy. No original recorded soundtrack exists for this silent-era production.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue, but Koko's actions and gestures communicated defiance and playfulness)

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Koko emerges from the inkwell and immediately begins causing mischief for the animator

- The series of increasingly elaborate traps the animator sets for Koko, each failing in comical fashion

- The climactic scene where Koko seemingly gains the upper hand and turns the tables on his creator

Did You Know?

- This was one of the earliest films featuring Koko the Clown, who became one of animation's first recurring characters

- The 'Out of the Inkwell' series was revolutionary for its time, blending live-action with animation

- Max Fleischer not only voiced but also physically appeared as the animator in many of these early shorts

- The film showcases one of the earliest examples of meta-humor in animation, where the character interacts with his creator

- The Rotoscope technique used in this film was patented by Max Fleischer in 1917 and was groundbreaking for creating realistic movement

- Koko was originally named 'Clown' and was modeled after Charlie Chaplin's tramp character

- These early shorts were produced on a shoestring budget in a cramped New York apartment before Fleischer Studios was officially established

- The interaction between live-action and animated elements was considered technically innovative for 1921

- This film predates Disney's Oswald the Lucky Rabbit by several years, making Koko one of animation's earliest stars

- The inkwell concept became so iconic that it remained the studio's opening sequence for decades

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews from 1921 praised the film's technical innovation and humor, with trade publications noting the clever integration of live-action and animation. Critics were particularly impressed by the smoothness of Koko's movement, achieved through the Rotoscope technique. The film was highlighted in animation journals as an example of the artistic possibilities of the medium. Modern film historians regard 'Invisible Ink' and its companion shorts as foundational works in animation history, often citing them in studies of early American animation. The film is frequently referenced in academic discussions about the development of meta-fiction in animated media and the evolution of character animation.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1921 were delighted by the novel concept of cartoons that seemed to come to life and interact with real people. The theatrical shorts were popular with both children and adults, who appreciated the sophisticated humor and technical wizardry. Koko the Clown quickly became a recognizable character, with audience letters to exhibitors requesting more of his adventures. The film's success helped establish the 'Out of the Inkwell' series as a regular feature in theaters. Contemporary audience reactions, as reported in trade papers, emphasized the wonder and amusement at seeing an animated character seemingly break free from the screen and engage with his creator.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Winsor McCay's 'Gertie the Dinosaur'

- Early vaudeville comedy acts

- Charlie Chaplin's Tramp character

- Contemporary newspaper comic strips

This Film Influenced

- Later 'Out of the Inkwell' series

- Disney's early 'Alice Comedies'

- Warner Bros.' 'You Ought to Be in Pictures'

- Tex Avery's 'TV of Tomorrow'

- Modern meta-animation like 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit'

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in archives and has been preserved by various film institutions including the Library of Congress and UCLA Film & Television Archive. Some copies show the wear and tear typical of films from this era, but the essential content remains viewable. The film has been included in various collections of early animation and Fleischer Studios retrospectives. Digital restorations have been undertaken by animation historians and preservationists, though the original nitrate elements have long since deteriorated.