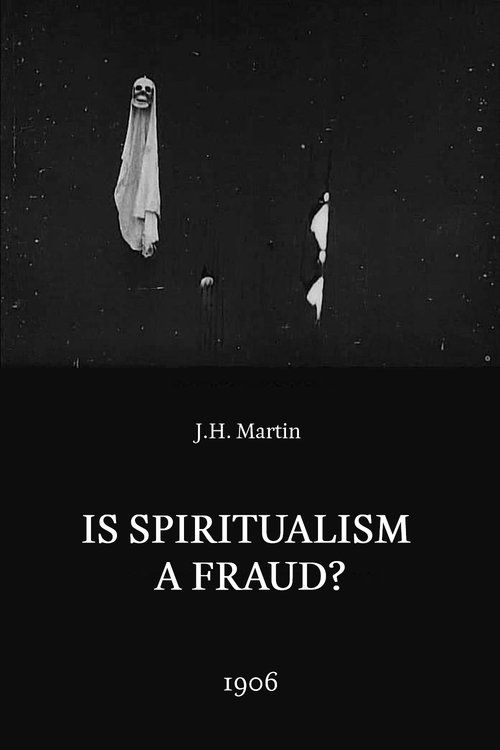

Is Spiritualism a Fraud? – The Medium Exposed

Plot

In this early comedic short film, a group of skeptical gentlemen attend a séance held by a fraudulent medium who uses various tricks to convince her clients of her supernatural powers. The men, suspicious of the medium's abilities, carefully observe her methods and soon discover the hidden wires, accomplices, and other contraptions used to create the illusion of spirit communication. Having exposed her as a charlatan, they decide to take revenge by turning her own tricks against her in an elaborate and humorous fashion. The film culminates in a chaotic scene where the medium is thoroughly embarrassed and her fraudulent practices are revealed to all. This early example of a 'trick film' combines comedy with a skeptical look at the popular spiritualist movement of the era.

Director

J.H. MartinAbout the Production

This film was produced during the early days of cinema when 'trick films' were extremely popular. The director J.H. Martin was known for his work in creating films that showcased special effects and camera tricks. The production utilized simple but effective special effects for the time, including hidden wires and trapdoors to simulate supernatural phenomena. The film was likely shot in a single day or two, which was typical for shorts of this period.

Historical Background

The year 1906 was a pivotal time in cinema history, with the medium transitioning from novelty to a form of entertainment with its own developing language and genres. This film emerged during the height of the spiritualist movement in Britain and America, a time when séances and mediumship were not only popular entertainment but also taken seriously by many including prominent scientists and intellectuals. The film's skeptical approach reflected growing public debate about the legitimacy of spiritualism, which had been fueled by high-profile exposures of fraudulent mediums. In cinema terms, 1906 was before the rise of feature films, with shorts dominating the market. This film belongs to the 'trick film' genre popularized by Georges Méliès, which showcased special effects and camera magic. The British film industry was still in its infancy, with companies like Gaumont establishing production facilities in London to compete with the dominant French and American markets.

Why This Film Matters

This film holds cultural significance as one of the earliest cinematic works to engage with the spiritualist movement, reflecting the public's simultaneous fascination with and skepticism toward supernatural claims. It represents an early example of cinema being used as a tool for public education and skepticism, using the new medium to 'expose' what many saw as fraud. The film also exemplifies the early development of the comedy genre in cinema, particularly the 'revenge comedy' structure that would become a staple of later films. Its preservation provides modern audiences with a window into the entertainment and concerns of Edwardian society. Additionally, the film demonstrates how early cinema quickly moved beyond simple actualities to develop narrative forms that engaged with contemporary social issues and debates.

Making Of

The making of 'Is Spiritualism a Fraud? – The Medium Exposed' represented the early film industry's fascination with exposing deception through the new medium of cinema. Director J.H. Martin, working for Gaumont, employed innovative camera techniques and practical effects to create the illusion of supernatural phenomena before systematically revealing how each trick was accomplished. The production likely took place in Gaumont's simple studio facilities in London, with minimal sets and props. The cast would have been drawn from the small pool of professional actors working in British film at the time, many of whom came from music hall backgrounds. The film's structure—building up the supernatural illusion and then deconstructing it—required careful planning of camera placement and editing to maintain the comedic timing while ensuring the 'exposé' elements were clear to the audience.

Visual Style

The cinematography in this 1906 film reflects the technical limitations and creative solutions of early cinema. Shot on black and white film stock, the camera would have been stationary, as was typical of the period, with all action taking place within a single frame. The cinematographer utilized basic lighting techniques, likely relying on natural light from studio skylights supplemented by arc lamps when necessary. The film's special effects, including the apparent supernatural phenomena, were achieved through practical effects such as hidden wires, trapdoors, and careful editing. Some scenes may have been tinted by hand, a common practice to add visual interest or indicate different times of day. The cinematography prioritized clarity over artistry, ensuring that both the tricks and their exposures were clearly visible to the audience.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in terms of technical innovation, this film demonstrated solid execution of existing cinematic techniques for its time. The effective use of practical effects to simulate supernatural phenomena before revealing their mechanics showed an understanding of how to use cinema both to create and deconstruct illusion. The film's editing, though simple by modern standards, effectively built tension during the séance scenes and provided comic timing for the exposure and revenge sequences. The production made good use of the limited camera mobility of the period, staging action clearly within the frame. The film also represents an early example of narrative structure in cinema, with a clear setup, development, and resolution within its brief running time.

Music

As a film from 1906, this was a silent production with no synchronized soundtrack. During original exhibition, the film would have been accompanied by live musical performance, typically a pianist or small ensemble in the cinema. The music would have been selected to match the mood of each scene—mysterious and atmospheric during the séance sequences, then becoming more playful and comedic during the exposure and revenge scenes. The specific musical selections would have been at the discretion of the cinema's musical director, though they might have included popular songs of the era or classical pieces appropriate to the mood. Modern screenings of the film are typically accompanied by newly composed scores or carefully selected period-appropriate music.

Famous Quotes

The medium: 'I feel a presence... a spirit wishes to communicate!' (followed by the revelation of hidden wires)

One skeptic to another: 'Watch carefully, my friend. The hand is quicker than the eye.'

The medium (exposed): 'But... but the spirits... they were real!'

A gentleman seeking revenge: 'Turnabout is fair play, madam. Let us show you some real magic!'

Memorable Scenes

- The séance scene where various supernatural phenomena occur, including floating objects and mysterious messages, all created through visible trick photography and practical effects.

- The exposure sequence where the gentlemen systematically reveal each of the medium's tricks, including pulling aside curtains to show hidden assistants and demonstrating the wire mechanisms.

- The revenge scene where the men turn the medium's own tricks against her, creating chaos and comedy as they manipulate her props and effects.

- The final scene showing the medium's humiliation as her clients realize they have been deceived, providing a satisfying moral conclusion.

Did You Know?

- This film is one of the earliest cinematic examinations of spiritualism, reflecting the public fascination and skepticism with the movement in the early 20th century.

- The film was part of a popular genre of 'exposé films' that revealed the tricks behind various forms of entertainment and deception.

- Director J.H. Martin was a pioneer in British cinema who worked extensively with the Gaumont company.

- The original film was tinted by hand for certain scenes, a common practice in early cinema to add visual interest.

- At only 3 minutes long, this film was designed to be shown as part of a varied program of shorts, which was the typical exhibition format of the time.

- The medium character was likely played by a male actor in drag, which was common in early comedy films.

- This film survives today in the BFI National Archive, making it one of the relatively preserved British films from 1906.

- The film's release coincided with the height of the spiritualist movement in Britain, when many prominent figures were involved in séances.

- The revenge sequence in the film was considered quite elaborate for its time, utilizing multiple camera tricks in quick succession.

- This film was distributed internationally, with versions made for both British and American markets.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of the film is difficult to trace due to the limited film journalism of 1906, but trade publications like The Bioscope and The Optical Lantern and Cinematograph Journal likely noted it as an example of Gaumont's quality productions. The film would have been praised for its clever use of special effects and its humorous approach to a current social phenomenon. Modern critics and film historians view the film as an important early example of the exposé genre and a valuable document of Edwardian attitudes toward spiritualism. The British Film Institute includes it among significant early British films, noting its technical achievements and cultural relevance. Film scholars often cite it when discussing the development of comedy in early cinema and the medium's early engagement with skeptical inquiry.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1906 reportedly found the film highly entertaining, as it combined the popular elements of trick photography with the satisfying exposure of deception. The séance setting would have been familiar to many viewers, either through direct experience or through extensive media coverage of spiritualism. The comedic revenge plot provided the kind of clear, satisfying resolution that early film audiences appreciated. The film's short length and visual gags made it ideal for the varied programs of shorts that constituted typical cinema exhibitions of the period. While specific audience reactions from the time are not extensively documented, the film's survival and preservation suggest it was considered successful enough to warrant retention. Modern audiences viewing the film through archives or screenings of early cinema often find it fascinating for its historical value and surprisingly sophisticated comedy.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The work of Georges Méliès, particularly his trick films and exposés of magic

- Popular spiritualist literature and exposé books of the period

- Music hall comedy acts featuring exposure of fraud

- Earlier actuality films showing séances

- The tradition of skeptical inquiry into spiritualism

This Film Influenced

- Later exposé films revealing magic tricks

- Comedy films featuring revenge plots

- Films skeptical of supernatural claims

- Early detective films that reveal methods of crime

- The tradition of 'how-it's-done' films in cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the BFI National Archive. While complete, the nitrate original has been transferred to safety stock and digitized for preservation. Some color tinting from the original release may be lost, but the black and white image is in good condition for a film of this vintage.