Japanese Fantasy

Plot

Japanese Fantasy (1907) presents a whimsical series of animated illusions featuring inanimate objects that come to life through Émile Cohl's pioneering animation techniques. The film begins with a Japanese lantern that transforms and animates, followed by several dolls that dance and move with supernatural life. Chickens, mice, and grasshoppers appear throughout the short, engaging in impossible movements and transformations that defy natural laws. The entire piece serves as a showcase of early animation possibilities, with each element seamlessly transitioning between reality and fantasy. The film concludes with a grand spectacle where all the animated elements interact in a chaotic yet harmonious display of magical animation.

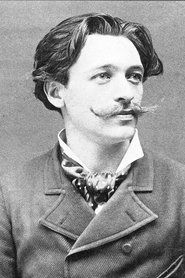

Director

About the Production

Japanese Fantasy was created using cutout animation techniques, a method Émile Cohl helped pioneer. The film was likely produced in a small studio space using simple props and materials. Cohl would have meticulously moved each element frame by frame, creating the illusion of movement through persistence of vision. The Japanese theme reflects the growing Western fascination with Japanese art and culture (Japonisme) that was popular in Europe during this period.

Historical Background

Japanese Fantasy was created in 1907, a pivotal year in early cinema when filmmakers were still discovering the medium's possibilities. This was the era when film transitioned from mere recording devices to vehicles for fantasy and imagination. The film emerged during the Belle Époque in France, a period of great artistic innovation and cultural exchange. The growing fascination with Japanese culture in Europe, known as Japonisme, influenced many artists of the period, including Cohl. Cinema itself was only about 12 years old, and animation was in its absolute infancy, with pioneers like Cohl, Georges Méliès, and J. Stuart Blackton experimenting with what was possible. The film industry was consolidating around major studios like Gaumont and Pathé, which were producing hundreds of short films annually to feed the growing demand from nickelodeons and early movie theaters worldwide.

Why This Film Matters

Japanese Fantasy represents a crucial milestone in the development of animation as an art form. As one of Cohl's early animated works, it helped establish the language and techniques that would define animation for decades to come. The film demonstrates how animation could create impossible scenarios that live-action could not achieve, establishing animation as a medium for fantasy and imagination. Its Japanese theme reflects the cultural exchange between East and West that characterized the early 20th century, showing how cinema could serve as a vehicle for cultural representation and exploration. The film is part of Cohl's legacy as a pioneer who proved that drawings and objects could be brought to life on screen, paving the way for the entire animation industry. It stands as an example of how early filmmakers pushed the boundaries of what was technically and artistically possible in cinema's first decade.

Making Of

Émile Cohl created Japanese Fantasy during his productive period at Gaumont, where he was one of the studio's most innovative filmmakers. The production would have taken place in a makeshift studio with basic lighting equipment, as film production was still in its infancy. Cohl likely worked alone or with minimal assistance, personally manipulating each paper cutout and prop between camera exposures. The Japanese aesthetic elements were probably inspired by the popular Japanese prints and art objects that were flooding European markets. The animation process was incredibly laborious, requiring Cohl to make tiny adjustments to each element for every frame of film. The film's brief runtime belies the hours of painstaking work involved in its creation. Cohl's background as a caricaturist influenced his approach, bringing a whimsical, cartoon-like quality to the animated figures.

Visual Style

The cinematography in Japanese Fantasy would have been rudimentary by modern standards, using stationary cameras typical of early film production. The visual style relied on flat, two-dimensional compositions against simple backgrounds, with the focus entirely on the animated elements. Cohl would have used basic lighting setups to ensure the paper cutouts and props were clearly visible against their backgrounds. The camera work was likely straightforward and functional, serving primarily to document the animation rather than create visual interest through movement or angles. The film's visual appeal came from the clever animation itself rather than sophisticated cinematography techniques.

Innovations

Japanese Fantasy represents an important technical achievement in the development of stop-motion animation. Cohl's use of paper cutouts and three-dimensional objects animated frame by frame was groundbreaking for its time. The film demonstrates early mastery of the principles of persistence of vision, creating smooth motion through carefully planned incremental movements. The transformation effects in the film show sophisticated understanding of how objects could appear to morph and change through animation techniques. The film's survival, even in fragmentary form, is itself a technical achievement considering the unstable nature of early nitrate film stock. Cohl's work on this film helped establish fundamental animation techniques that would be refined and expanded upon by future generations of animators.

Music

As a silent film from 1907, Japanese Fantasy would have been accompanied by live music during its theatrical exhibitions. The musical accompaniment would likely have been provided by a pianist or small orchestra in the theater, playing appropriate mood music to enhance the film's fantastical elements. The score might have included popular Japanese-inspired melodies of the period or generic exotic-sounding music to match the film's theme. Some theaters might have used mechanical music devices like player pianos or phonographs to provide musical accompaniment. The specific musical selections would have varied from theater to theater, as there was no standardized score for the film.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where the Japanese lantern comes to life and begins to move with supernatural grace

- The scene where multiple dolls dance and interact in impossible ways

- The finale where chickens, mice, and grasshoppers all animate simultaneously in a chaotic display

Did You Know?

- This film represents one of the earliest examples of stop-motion animation in cinema history

- Émile Cohl is often called 'the father of the animated cartoon' and created over 250 animated films

- The film was produced by Gaumont, one of the world's first and most important film companies

- Japanese Fantasy was released during the height of the Japonisme movement in Europe

- The film likely used paper cutouts and simple props animated through frame-by-frame photography

- At only 2 minutes long, it was typical of early cinema shorts that played before feature presentations

- Cohl was originally a political caricaturist before transitioning to film animation

- The film survives today only in fragments, as many early films were lost due to the unstable nitrate film stock

- This was created just 12 years after the invention of cinema by the Lumière brothers

- The Japanese theme was exotic and mysterious to European audiences of the time

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of Japanese Fantasy are scarce due to the limited film criticism of the era, but trade publications of the time noted Cohl's innovative animation techniques. Modern film historians and scholars recognize the film as an important early example of animation, though it is often overshadowed by Cohl's more famous work 'Fantasmagorie' (1908). Critics today appreciate the film for its historical significance and its role in establishing animation as a cinematic art form. The film is frequently cited in academic studies of early animation and is recognized for its contribution to the development of stop-motion techniques. Animation historians regard Cohl's work from this period as foundational to the medium, with Japanese Fantasy serving as an example of his early experimentation with bringing inanimate objects to life.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th century audiences would have been amazed by the magical transformations and impossible movements in Japanese Fantasy, as animation was still a novel and wondrous phenomenon. The film's exotic Japanese theme would have added to its appeal, offering viewers a glimpse into what they imagined as mysterious Eastern culture. Contemporary audiences at nickelodeons and early cinemas likely responded with wonder to the sight of objects coming to life, as the concept of animation was still new and magical to most viewers. The film's brief, punchy format was perfect for the short attention spans of early cinema audiences who were accustomed to a rapid succession of different films in a single program. Today, the film is primarily viewed by film students, historians, and animation enthusiasts who appreciate its historical importance and pioneering techniques.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès' trick films

- Japanese woodblock prints

- European Japonisme movement

- Early magic lantern shows

This Film Influenced

- Fantasmagorie (1908)

- Later stop-motion animations

- The work of Ladislas Starevich

- Willis O'Brien's early animations

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Japanese Fantasy is considered a partially lost film, with only fragments surviving in film archives. Some portions may exist in collections such as the Cinémathèque Française or other European film archives. The film suffers from the common fate of many early cinema works that were lost due to the deterioration of nitrate film stock or were simply discarded after their commercial usefulness ended. Restoration efforts have been limited due to the incomplete nature of the surviving material. What remains provides valuable insight into early animation techniques but represents only a portion of Cohl's original vision.