Kiri-Kis

Plot

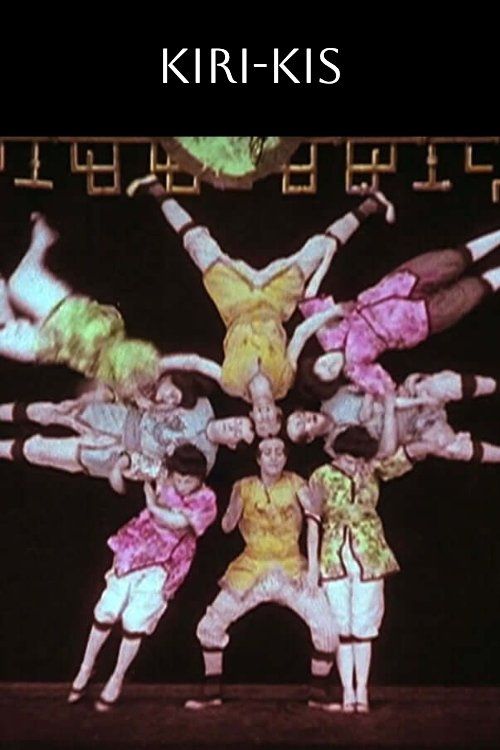

In this early trick film, a family troupe of acrobats appears in Japanese-inspired costumes and makeup, performing seemingly impossible feats before the camera. The performers demonstrate extraordinary acrobatic abilities that defy the laws of physics, including impossible jumps, transformations, and magical disappearances. Through the innovative use of stop-motion techniques and multiple exposures, director Segundo de Chomón creates the illusion of supernatural abilities. The film culminates in a spectacular display of the troupe's most impressive stunts, each more unbelievable than the last, showcasing the technical wizardry of early cinema. The entire performance serves as a demonstration of the magical possibilities of film itself, blurring the line between live performance and cinematic illusion.

Director

About the Production

This film was produced during Segundo de Chomón's prolific period working for Pathé Frères, where he became known as the Spanish Méliès for his innovative trick films. The production required elaborate costumes designed to evoke Japanese aesthetics for European audiences, reflecting the period's fascination with Japonisme. The film's special effects were achieved entirely in-camera using techniques such as multiple exposures, substitution splices, and stop-motion photography, requiring precise timing and coordination from both the performers and the camera operator.

Historical Background

1907 was a pivotal year in early cinema, occurring during the transition from simple actualities to more complex narrative and trick films. The film industry was rapidly consolidating, with Pathé Frères establishing itself as the dominant global producer. This period saw the emergence of specialized genres, with trick films becoming particularly popular for their ability to showcase cinema's unique capabilities beyond mere recording. The fascination with Japanese culture reflected the broader cultural phenomenon of Japonisme that had swept Europe since the opening of Japan to Western trade in the 1850s. Cinema was still largely a fairground and vaudeville attraction, with films like 'Kiri-Kis' serving as spectacular novelties between live acts. The technical sophistication of films like this demonstrated how quickly the medium was evolving from simple recordings to complex visual narratives.

Why This Film Matters

'Kiri-Kis' represents an important milestone in the development of cinematic special effects and the fantasy genre. The film exemplifies how early cinema explored themes of transformation and impossibility, establishing tropes that would continue throughout film history. Its combination of acrobatic performance with camera trickery illustrates the medium's unique ability to transcend the limitations of live performance. The film's Orientalist themes, while problematic by modern standards, reflect important cultural attitudes of the period and demonstrate cinema's role in shaping and reflecting popular fascinations. As part of Segundo de Chomón's body of work, it contributes to our understanding of how special effects techniques were developed and refined in cinema's first decade. The film also serves as an example of how early filmmakers created international appeal through exotic themes, helping establish cinema as a global medium.

Making Of

The making of 'Kiri-Kis' exemplifies the resourceful ingenuity of early filmmakers working with limited technology. Segundo de Chomón, working at the height of his creative powers for Pathé Frères, would have directed the performers through multiple takes to achieve the precise timing required for the trick effects. The film's special effects were accomplished through painstaking frame-by-frame manipulation, with the performers often having to hold difficult positions while the camera was stopped and restarted. The Japanese-inspired costumes and makeup were created in Pathé's extensive workshops, reflecting the company's commitment to visual spectacle. The production would have taken place in Pathé's studio facilities in Paris or Vincennes, where de Chomón had access to the company's considerable resources. The film's brief runtime was typical of the era, when even the most elaborate productions rarely exceeded a few minutes, making every second count in terms of visual impact.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Kiri-Kis' showcases the sophisticated in-camera techniques that made Segundo de Chomón famous. The film employs multiple exposures to create the illusion of performers appearing and disappearing, substitution splices for instantaneous transformations, and stop-motion photography for impossible movements. The camera work is static, as was typical of the period, but the frame is used dynamically with performers moving through different spatial planes. The lighting would have been bright and even to ensure clear visibility of the trick effects, likely using the powerful arc lights available in Pathé's studios. The composition carefully arranges performers to maximize the impact of the special effects while maintaining visual clarity. The black and white photography creates strong contrasts that enhance the magical quality of the illusions.

Innovations

'Kiri-Kis' demonstrates several important technical achievements in early cinema special effects. The film showcases advanced mastery of multiple exposure techniques, allowing performers to appear and disappear within the same frame. The substitution splices used for transformations are executed with remarkable precision, considering the manual nature of film editing in 1907. The stop-motion sequences reveal an understanding of frame-by-frame animation principles that were still being developed. The coordination between live performance and camera tricks represents a sophisticated approach to cinematic choreography. The film also demonstrates the effective use of in-camera matting techniques to create composite images. These achievements were particularly impressive given the primitive equipment available and the manual nature of film processing and editing at the time.

Music

As a silent film from 1907, 'Kiri-Kis' would have been accompanied by live music during its original exhibitions. The musical accompaniment would typically have been provided by a pianist or small ensemble in cinema venues, or by a full orchestra in more prestigious theaters. The music would have been chosen to match the film's exotic theme and spectacular action, likely incorporating popular Japanese-inspired melodies of the period or classical pieces with an appropriate tempo. The accompaniment would have emphasized the magical and mysterious elements of the film while synchronizing with the rhythm of the acrobatic performances. In modern screenings, the film is typically accompanied by period-appropriate music or newly composed scores that evoke the early 20th century aesthetic.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, 'Kiri-Kis' contains no spoken dialogue, but its visual spectacle communicates universally across language barriers.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic sequence where the acrobatic family performs a series of impossible transformations, with members disappearing and reappearing in different positions through seamless editing tricks, creating a mesmerizing display of early cinematic magic that still astonishes viewers with its technical precision and visual inventiveness.

Did You Know?

- The title 'Kiri-Kis' is likely a phonetic approximation of Japanese sounds created for European audiences, reflecting the Western fascination with Japanese culture in the early 1900s.

- Segundo de Chomón was often called 'The Spanish Méliès' due to his similar style of fantasy and trick films, though he developed many techniques independently.

- This film was part of Pathé's extensive catalog of trick films that were popular attractions in fairgrounds and early cinema venues.

- The performers were likely members of de Chomón's own family or regular collaborators from his Pathé productions.

- The film demonstrates de Chomón's mastery of in-camera effects, predating more sophisticated optical printing techniques.

- Like many films of this era, it would have been hand-colored frame by frame for special screenings, though most surviving copies are in black and white.

- The Japanese theme was part of a broader trend of Orientalism in European entertainment of the period.

- This film showcases de Chomón's ability to combine live performance with cinematic trickery, creating a unique hybrid of theater and film.

- The acrobatic stunts, while enhanced by camera tricks, required real athletic ability from the performers.

- This type of short film was typically shown as part of a varied program alongside newsreels, other shorts, and sometimes live performances.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'Kiri-Kis' would have appeared in trade publications and newspapers of the era, where it was likely praised for its technical ingenuity and visual spectacle. Early cinema reviewers often focused on the novelty of trick effects and the apparent impossibility of the stunts shown. Modern film historians and scholars recognize 'Kiri-Kis' as an exemplary work of early trick cinema, noting Segundo de Chomón's technical prowess and creative vision. The film is frequently cited in studies of early special effects and the development of the fantasy genre in cinema. Critics today appreciate the film both for its historical significance and its continued ability to entertain through its clever visual illusions.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th century audiences would have received 'Kiri-Kis' with wonder and amazement, as trick films were among the most popular attractions of the period. Viewers at fairgrounds, music halls, and early cinema venues would have been particularly impressed by the seemingly impossible acrobatic feats, many of which appeared to defy the laws of physics. The exotic Japanese theme would have added to the film's appeal, tapping into contemporary fascination with Eastern culture. The film's brief but action-packed nature made it ideal for the varied programming typical of early cinema exhibitions. Modern audiences viewing the film in archival contexts or film festivals often express admiration for the technical sophistication achieved with such primitive equipment, as well as the enduring entertainment value of its visual tricks.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès' trick films

- Japanese theatrical traditions

- Circus and vaudeville performances

- Orientalist art and literature

This Film Influenced

- Later trick films by Pathé

- Fantasy shorts of the 1910s

- Early special effects in narrative cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Preserved in film archives, with copies held at major institutions including the Cinémathèque Française and other European film archives. The film survives in 35mm format and has been digitized for preservation and accessibility. Some versions may show signs of deterioration typical of films from this period, but the visual effects remain clear and impressive.