Ko-Ko's Tattoo

"The Tattoo That Came to Life!"

Plot

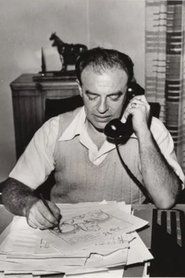

In this innovative Out of the Inkwell short, animator Max Fleischer draws a small black cat tattoo on his live-action coworker's arm during a break. When the tattoo comes to life, it leaps off the arm and begins causing mischief around the studio. The animated clown Fitz (Ko-Ko) spots the mischievous cat and engages in a wild chase throughout the animated world, creating chaos as they run through various backgrounds and interact with animated objects. The pursuit culminates in a climactic scene where Fitz finally corners the cat, leading to a humorous resolution that returns the cat to its tattoo form on the coworker's arm, leaving both the animated and live-action characters exhausted but entertained.

Director

Cast

About the Production

This short utilized the groundbreaking Rotoscope technique invented by Max Fleischer, which allowed for realistic integration of live-action and animation. The production involved shooting Max Fleischer and his coworker on film, then tracing their movements frame by frame to create the live-action segments. The animated portions were drawn on paper, photographed, and then combined with the live-action footage using optical printing. The tattoo cat animation required particularly careful synchronization to make it appear as if it were truly emerging from and returning to the live-action actor's skin.

Historical Background

1928 was a pivotal year in cinema history, standing at the precipice of the sound revolution that would forever change filmmaking. The Jazz Singer had premiered in October 1927, and by 1928, studios were rushing to convert to sound production. Fleischer Studios, like many animation houses, was still perfecting their silent techniques while preparing for the transition to sound. This period saw the height of the Roaring Twenties cultural boom, with Art Deco design influencing everything from architecture to animation. The popularity of tattoos was growing in mainstream American culture, moving from sailor subculture into broader society. Animation itself was evolving from simple novelty acts into sophisticated storytelling medium, with studios like Fleischer, Disney, and the Van Beuren Corporation competing for audience attention in an increasingly crowded market.

Why This Film Matters

'Ko-Ko's Tattoo' represents a crucial milestone in the evolution of animation as an art form. The Out of the Inkwell series, of which this short is a part, pioneered the integration of live-action and animation, a technique that would become fundamental to later films from Disney's 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit' to modern CGI blockbusters. The film's playful meta-commentary on the animation process, showing the animator literally drawing characters that come to life, helped establish animation as a self-aware medium capable of sophisticated humor. Ko-Ko the Clown was one of the first animated characters with a distinct personality, paving the way for later icons like Mickey Mouse and Betty Boop. The technical innovations displayed in this short, particularly the seamless blending of different visual realities, influenced generations of animators and demonstrated the artistic possibilities of the medium beyond simple entertainment.

Making Of

The production of 'Ko-Ko's Tattoo' represented the pinnacle of Fleischer Studios' silent animation techniques. Max Fleischer and his brother Dave worked closely with their team of animators to create the seamless interaction between the live-action world and the animated realm. The rotoscoping process, which Max had patented in 1917, was used extensively to ensure that the animated Fitz moved with naturalistic fluidity. The tattoo cat sequence required innovative animation techniques to create the illusion of a two-dimensional drawing transforming into a three-dimensional animated character. The studio's cramped New York location meant that animators often worked in close quarters, leading to collaborative problem-solving and the development of new animation shortcuts. The sound of the studio's mechanical cameras and optical printers created a constant backdrop during production, as this was still the silent era of filmmaking.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Ko-Ko's Tattoo' was groundbreaking for its time, combining traditional live-action cinematography with innovative animation techniques. The live-action segments were shot on black-and-white film using standard cameras of the era, with careful attention to lighting to facilitate the later integration with animated elements. The animation was photographed using the rostrum camera system, which allowed for precise frame-by-frame capture of the hand-drawn images. The most technically challenging aspect was the optical printing process that combined the live-action and animation footage, requiring multiple passes through the printer to create the seamless composite. The visual style employed strong contrasts and clear outlines to ensure the animated characters would stand out against the live-action background, a technique that became standard practice in mixed-media animation.

Innovations

The most significant technical achievement in 'Ko-Ko's Tattoo' was the seamless integration of live-action and animation using the rotoscope technique. Max Fleischer's patented rotoscope allowed animators to trace live-action footage frame by frame, creating realistic movement for animated characters. The film also demonstrated mastery of the optical printer, which was used to composite the different visual elements. The animation of the tattoo cat transforming from a 2D drawing to a 3D animated character required innovative approaches to perspective and movement. The short also showcased the studio's expertise in character animation, with Ko-Ko displaying emotional range and physical comedy that was advanced for the period. The synchronization of timing between the live-action performer's movements and the animated character's responses demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of cross-medium storytelling.

Music

As a silent film from 1928, 'Ko-Ko's Tattoo' did not have an original synchronized soundtrack. However, when shown in theaters, it was accompanied by live musical performances, typically featuring a theater organist or small orchestra. The musical accompaniment would have included popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and original improvisations that matched the on-screen action. The chase scenes between Ko-Ko and the cat would have been accompanied by fast-paced, energetic music, while quieter moments would have featured more melodic compositions. Some theaters may have used compiled cue sheets provided by the distributor to guide the musical accompaniment. The transition to sound in 1929 meant that later Fleischer shorts would feature synchronized music and sound effects, but 'Ko-Ko's Tattoo' represents the pinnacle of the studio's silent era work.

Famous Quotes

While this is a silent film without dialogue, intertitles included: 'Watch me draw something special!' and 'That tattoo has a mind of its own!'

The film's visual humor conveyed messages through action rather than words

Memorable Scenes

- The magical moment when the tattoo cat leaps from the coworker's arm and becomes fully animated, showcasing the technical mastery of the Fleischer team

- The climactic chase sequence where Ko-Ko pursues the cat through various animated backgrounds, demonstrating the studio's skill in creating dynamic movement and comedic timing

Did You Know?

- This is one of the later Out of the Inkwell shorts before the series transitioned to sound in 1929

- The tattoo cat character was one of the first examples of an animated object coming to life from a drawing within a drawing

- Max Fleischer appears as himself in the live-action segments, which was typical for the Out of the Inkwell series

- The coworker who receives the tattoo was actually one of the Fleischer Studios animators, though his name is not credited

- This short showcases the technical mastery of combining live-action and animation years before Disney would perfect similar techniques

- The cat's animation was particularly challenging because it had to appear two-dimensional when on the arm but three-dimensional when animated

- Ko-Ko was originally called 'Clown' but was renamed 'Ko-Ko' in 1924, though some shorts still referred to him as Fitz

- The tattoo motif was inspired by the growing popularity of tattoos in 1920s American culture

- This short was released just months before the introduction of sound in motion pictures, making it one of the last great silent animated shorts

- The film's title card was designed in the distinctive Art Deco style that was becoming popular in 1928

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade publications like Variety and The Moving Picture World praised the technical innovation and humor of 'Ko-Ko's Tattoo.' Critics noted the cleverness of the tattoo concept and the smooth integration of live-action and animation elements. The short was particularly appreciated for its visual gags and the expressive animation of both Ko-Ko and the mischievous cat. Modern animation historians view this short as an exemplary example of late-silent era animation, showcasing the sophistication that had been achieved in the medium before the sound transition. Film scholars often cite this and other Out of the Inkwell shorts as evidence that American animation had reached artistic maturity well before the Disney golden age began.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1928 responded enthusiastically to 'Ko-Ko's Tattoo' and other Out of the Inkwell shorts. The series had built a loyal following since its inception in 1918, with viewers delighted by the novel concept of animated characters interacting with real people. Theater audiences particularly enjoyed the meta-humor of seeing the animator's hand literally create the cartoon world. Children were captivated by the magical transformation of the tattoo into a living character, while adults appreciated the technical wizardry and sophisticated visual comedy. The short's brief runtime made it perfect for theater programs, where it often appeared alongside newsreels and feature films. Audience letters to exhibitors frequently mentioned Ko-Ko shorts as highlights of their movie-going experience.

Awards & Recognition

- No specific awards were recorded for this individual short, though the Out of the Inkwell series received recognition from animation societies

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Winsor McCay's 'Gertie the Dinosaur' (1914) for live-action/animation interaction

- Early Felix the Cat cartoons for character design

- Vaudeville comedy traditions for physical humor

This Film Influenced

- Later Out of the Inkwell and Talkartoons series

- Disney's 'Alice Comedies' for live-action/animation mixing

- Modern films like 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit' for similar techniques

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in archived form and has been preserved by various film archives including the Library of Congress and UCLA Film & Television Archive. Some copies show signs of nitrate decomposition typical of films from this era, but complete versions are available for viewing. The film has been included in several Fleischer Studios compilation releases and is occasionally screened at film festivals specializing in classic animation.