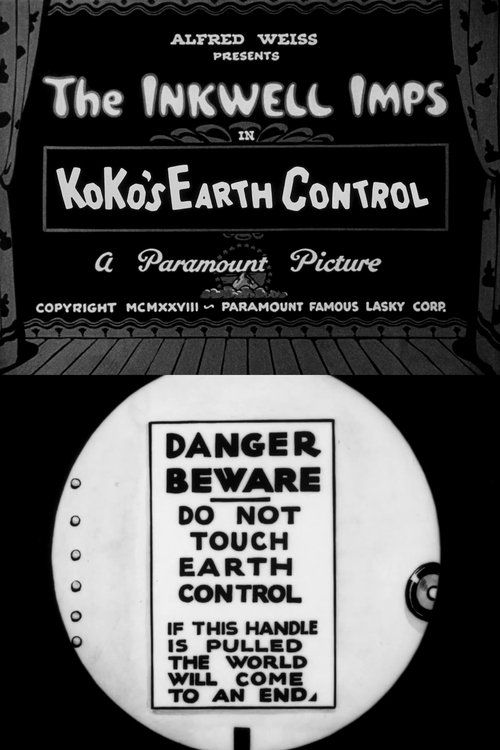

KoKo's Earth Control

Plot

In this surreal Out of the Inkwell adventure, Ko-Ko the Clown and his loyal canine companion Fitz wander into a mysterious building filled with enormous levers that control various aspects of the Earth. When Fitz curiously pulls one of the control levers, the world immediately descends into chaos as gravity reverses, buildings tumble, and natural phenomena go haywire. The cartoon showcases the Fleischer brothers' signature blend of live-action and animation as the real-world animator (Max Fleischer) struggles to contain the mayhem created by his mischievous characters. As the destruction escalates, Ko-Ko and Fitz must navigate their topsy-turvy environment while the animator attempts to restore order to their animated world. The film culminates in a frantic race against time as the lever-pulling consequences threaten to permanently alter their animated reality.

Director

About the Production

This film utilized the Fleischer Studios' innovative combination of live-action and animation, featuring Max Fleischer himself interacting with the cartoon characters. The production employed the rotoscoping technique that Max Fleischer had patented, where live-action footage was traced to create more realistic movement. The film was created during the transitional period between silent and sound cinema, showcasing the studio's mastery of visual storytelling before dialogue became standard. The control room setting allowed for creative visual gags and demonstrated the Fleischers' fascination with technology and machinery, which would become a recurring theme in their later works.

Historical Background

The film was produced in late 1928, a transformative year in cinema history when the industry was rapidly transitioning from silent films to 'talkies.' This period saw the release of 'The Jazz Singer' in 1927, which had revolutionized the industry, and by 1928, most major studios were converting to sound production. The Fleischer Studios, like other animation companies, faced the challenge of adapting their visual storytelling to include synchronized sound. This film represents the culmination of silent-era animation techniques, showcasing the sophisticated visual gags and storytelling that had been developed over the previous decade. The late 1920s also saw the rise of modernism and fascination with technology and machinery, reflected in the film's control room setting. The stock market crash of 1929 would soon follow, making this film part of the final creative burst of the Roaring Twenties before the Great Depression reshaped American entertainment.

Why This Film Matters

'KoKo's Earth Control' holds significant cultural importance as a representative work of one of animation's pioneering studios. The Fleischer Studios, founded by brothers Max and Dave, were instrumental in developing many animation techniques that would become industry standards. This film exemplifies their innovative approach to blending live-action and animation, a technique that would influence countless future works. Ko-Ko the Clown was one of the first animated characters with a distinct personality and the ability to interact with his creator, establishing a meta-narrative approach that would become common in later animation. The film's exploration of control and chaos through animated imagery reflects the anxieties of an industrial age grappling with rapidly advancing technology. As one of the last silent Ko-Ko cartoons, it represents a pivotal moment in animation history, capturing the art form at its silent-era peak before the transition to sound would permanently change the medium.

Making Of

The production of 'KoKo's Earth Control' took place during a pivotal moment in animation history at Fleischer Studios in New York City. Dave Fleischer, who directed the film, worked closely with his brother Max, who not only created the Ko-Ko character but also appeared in the live-action segments. The studio employed a team of animators who worked on the complex combination shots, carefully matching the animated characters' movements to the live-action footage. The control room sequence required particularly intricate animation, with multiple moving parts and effects that had to be synchronized perfectly. The Fleischers were known for their experimental approach, and this film showcases their willingness to push the boundaries of what was possible in silent animation. The production team often worked long hours to achieve the detailed effects, with some scenes requiring dozens of drawings per second of footage to create the illusion of smooth movement during the chaotic sequences.

Visual Style

The film's visual style represents the pinnacle of silent-era animation cinematography, featuring the Fleischer Studios' trademark blend of live-action and animation. The cinematography employed innovative techniques including the rotoscope process, which Max Fleischer had patented, allowing for more realistic movement in the animated characters. The control room sequences utilized multiple exposure techniques to create the illusion of massive machinery and simultaneous action. The film's visual composition carefully balanced the live-action footage of Max Fleischer with the animated world, creating a seamless integration that was revolutionary for its time. The strobe effects mentioned in modern descriptions were achieved through rapid animation techniques rather than optical effects, demonstrating the animators' mastery of their craft. The cinematography also featured dynamic camera movements within the animated sequences, creating a sense of depth and movement that was uncommon in animation of this period.

Innovations

This film showcased several significant technical achievements that were groundbreaking for 1928. The seamless integration of live-action and animation represented the culmination of techniques the Fleischers had been developing since 1918. The control room sequences featured complex multi-layered animation with numerous moving parts that had to be perfectly synchronized. The film employed advanced use of the rotoscope technique, allowing for more fluid and realistic character movement than was typical of the era. The strobe effects were created through innovative animation techniques rather than optical printing, demonstrating the studio's mastery of the medium. The film also featured some of the most sophisticated background animation of its period, with detailed mechanical elements that moved independently of the characters. These technical achievements established standards that would influence animation production for decades to come.

Music

As a silent film, 'KoKo's Earth Control' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The typical presentation would have featured a theater organist or small orchestra performing appropriate music synchronized with the on-screen action. The score likely included popular songs of 1928, classical pieces, and original incidental music composed specifically for the film. The control room sequences would have been accompanied by frantic, percussive music to enhance the sense of chaos, while quieter moments would have featured more melodic passages. No original score or specific musical cues for this film have survived, as was common with silent era productions where the music was improvised or arranged by individual theater musicians. The transition to sound in 1929 meant that this was among the last Ko-Ko cartoons to rely on live musical accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles and visual action rather than spoken quotes

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Ko-Ko and Fitz discover the mysterious control building

- The moment Fitz pulls the first lever and gravity begins to malfunction

- The escalating chaos as buildings tumble and natural phenomena go haywire

- The frantic attempts by Max Fleischer (in live-action) to restore order

- The final resolution sequence where the world slowly returns to normal

Did You Know?

- This was one of the last silent Ko-Ko cartoons before the transition to sound, making it historically significant as it represents the end of an era in animation history.

- The lever control concept was remarkably prescient, predating similar themes in later films like 'The Truman Show' by nearly 70 years.

- The film contains some of the most complex and rapid-fire visual effects of its era, with multiple simultaneous animated elements interacting with live-action footage.

- Ko-Ko the Clown was one of the first animated characters to regularly break the fourth wall, acknowledging his existence as a drawing and interacting with his creator.

- The destruction sequences were so elaborate that individual frames had to be redrawn multiple times to achieve the desired chaotic effect.

- This cartoon was part of the Out of the Inkwell series, which ran from 1918 to 1929 and was one of the most successful animated series of the silent era.

- The film's strobe effects mentioned in modern descriptions were created through rapid animation techniques rather than actual strobe lighting, showing the Fleischers' innovative approach to visual effects.

- Fitz the dog, Ko-Ko's companion, was one of the first recurring animal sidekicks in animation history.

- The control room setting with its massive levers and dials reflected the public's fascination with industrial technology and automation during the late 1920s.

- This short was released just months before the Fleischer Studios would begin producing sound cartoons, making it a bridge between two eras of animation technology.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its technical innovation and imaginative visual effects. The Motion Picture News noted the 'remarkable combination of live-action and animation' and highlighted the 'ingenious control room sequence' as a standout example of the Fleischers' technical prowess. The film was particularly appreciated for its sophisticated visual storytelling, which didn't require intertitles to convey the increasingly chaotic narrative. Modern animation historians view the short as a significant example of late-silent era animation, with Leonard Maltin noting it as 'one of the most technically impressive Ko-Ko cartoons' in his book 'Of Mice and Magic.' The film's strobe effects and rapid animation sequences are now studied as early examples of visual effects techniques that would become standard in later animation.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1928 responded enthusiastically to the film's visual spectacle and humor. The Ko-Ko cartoons had built a loyal following since their debut in 1918, and this installment delivered the kind of inventive mayhem that fans expected. The control room premise resonated with contemporary audiences who were fascinated by modern technology and automation. Children particularly enjoyed the sight gags and the character of Fitz the dog, while adults appreciated the more sophisticated meta-humor of the animator struggling to control his creation. The film's release in December 1928, during the holiday season, likely contributed to its positive reception as theaters programmed it as part of family-friendly entertainment packages. Modern audiences viewing the film today often express surprise at the sophistication of the visual effects and the film's prescient themes about technology and control.

Awards & Recognition

- No specific awards documented for this individual short film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Out of the Inkwell series cartoons

- George Méliès' fantasy films

- Charlie Chaplin's physical comedy

- Buster Keaton's mechanical gags

- German Expressionist cinema

- Industrial Revolution imagery

- Contemporary science fiction literature

This Film Influenced

- Later Fleischer Studios cartoons including Betty Boop and Popeye series

- Walt Disney's early sound cartoons

- Warner Bros. Looney Tunes meta-humor

- Modern meta-narrative animations like 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit'

- The Matrix' (control room concept)

- The Truman Show

- controlled reality theme)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in various film archives including the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. While some copies show signs of deterioration typical of nitrate film from this era, several good quality prints exist. The film has been digitally restored by animation historians and is available through specialized film archives and some public domain collections. The preservation status is considered good compared to many silent-era animations, as the Ko-Ko series was historically recognized as significant and thus more likely to be preserved.