Koko's Field Daze

"The Clown That Came Out of the Inkwell!"

Plot

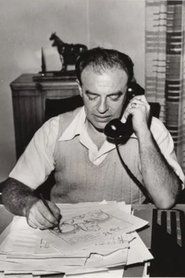

In this classic Out of the Inkwell short, Max Fleischer is seen preparing for a track and field competition, practicing his running and jumping techniques. As Max trains, his animated creation Ko-Ko the Clown emerges from the inkwell and immediately begins causing chaos, interfering with Max's athletic preparations in typical mischievous fashion. Ko-Ko's antics include sabotaging the training equipment, confusing the track markings, and generally making a nuisance of himself while trying to 'help' his creator. The short culminates in a humorous race sequence where Ko-Ko's interference leads to comic complications for Max's athletic endeavors, showcasing the innovative blend of live-action and animation that made the Fleischer studio famous.

Director

Cast

About the Production

This film was created using the Fleischer Studios' pioneering rotoscope technique, which allowed for realistic animation by tracing over live-action footage. The combination of live-action with Max Fleischer and animated Ko-Ko sequences required careful synchronization and multiple exposure techniques. The production utilized the innovative 'Out of the Inkwell' concept that Max Fleischer had developed, where animated characters would interact with their real-world creator.

Historical Background

Released in March 1928, 'Koko's Field Daze' emerged during a pivotal transition period in cinema history. The film industry was on the cusp of the sound revolution, with 'The Jazz Singer' having already premiered in October 1927. This placed Fleischer Studios at a crossroads, still perfecting their silent animation techniques while preparing for the inevitable shift to sound. The 1920s were also marked by a sports craze in America, with the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics approaching, making the track and field theme particularly relevant to contemporary audiences. The film represents the culmination of nearly a decade of the Fleischer brothers' animation innovations, building on techniques they had developed since founding their studio in 1921. This period saw animation transitioning from simple novelty acts to more sophisticated storytelling, with characters like Ko-Ko helping establish the animated short as a legitimate art form.

Why This Film Matters

'Koko's Field Daze' holds cultural significance as part of the pioneering Out of the Inkwell series that helped establish American animation as a distinct art form. The film's innovative blend of live-action and animation influenced countless future works, from Disney's 'Alice Comedies' to modern films that mix different media. Ko-Ko the Clown represented one of the first animated characters with a consistent personality and ongoing narrative, helping establish the concept of recurring animated characters that would become fundamental to the animation industry. The series also demonstrated the creative possibilities of breaking the fourth wall, with the animator-character relationship prefiguring meta-fictional techniques that would become common in later animation. The technical innovations showcased in this short, particularly the rotoscope technique, would influence animation for decades and help establish New York as a major center for animation production alongside Hollywood.

Making Of

The production of 'Koko's Field Daze' involved the innovative combination of live-action filming with Max Fleischer and traditional animation techniques. Max would perform the live-action segments first, often improvising his interactions with the yet-to-be-animated Ko-Ko. The animation team would then carefully animate Ko-Ko's movements to interact with Max's actions, using the rotoscope technique to ensure realistic movement and timing. The Fleischer studio was known for its experimental approach, and this short demonstrated their mastery of blending different media. The track and field props and settings were real, requiring careful planning to allow for the animated character's interference. The production team faced the challenge of maintaining consistent lighting and camera positioning between live-action and animation passes to create the seamless interaction that made these shorts so innovative.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Koko's Field Daze' employed innovative techniques for its time, combining standard live-action filming with special effects photography to enable the interaction between Max Fleischer and Ko-Ko. The live-action segments were filmed on sets designed to accommodate animated elements, with careful attention to lighting that would work for both live-action and animation compositing. Multiple exposure techniques were used to layer the animated Ko-Ko over the live-action footage, requiring precise timing and registration. The camera work had to remain consistent between takes to ensure the animated elements would align properly with the live-action background. The track and field sequences utilized wide shots to showcase both the athletic action and Ko-Ko's interference, demonstrating the cinematographers' skill in composing shots that served both the live-action and animated elements.

Innovations

The film showcased several significant technical achievements, most notably the advanced use of the rotoscope technique that Max Fleischer had patented. This allowed for more realistic animation of Ko-Ko's movements by tracing over live-action footage. The seamless integration of live-action and animation required innovative compositing techniques that were cutting-edge for 1928. The production demonstrated sophisticated understanding of animation timing and spacing, with Ko-Ko's movements carefully synchronized to interact believably with Max Fleischer's live-action performance. The inkwell effect, where Ko-Ko appears to emerge from and return to an actual inkwell, was achieved through clever animation combined with practical effects. These technical innovations helped establish standards that would influence animation production for decades.

Music

As a silent film from 1928, 'Koko's Field Daze' was originally presented without synchronized dialogue or sound effects. The musical accompaniment would have been provided live in theaters by pianists or small orchestras, using cue sheets provided by the studio. These cue sheets suggested appropriate musical selections for different scenes, with upbeat music for the athletic sequences and playful melodies for Ko-Ko's mischief. Some theaters may have used compiled scores featuring popular songs of the era. The transition to sound was beginning during this period, but this particular short was produced and released as a silent film, representing one of the last examples of the Fleischer Studios' silent-era work before they fully embraced sound technology.

Famous Quotes

Ko-Ko's mischievous laughter throughout the film

Max's exasperated reactions to Ko-Ko's interference

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Ko-Ko emerges from the inkwell to disrupt Max's training

- The climactic race sequence where Ko-Ko's interference leads to comic chaos on the track

Did You Know?

- This was one of the later films in the original Out of the Inkwell series before the transition to sound

- Ko-Ko the Clown was one of the first animated characters to have a distinct personality and recurring role

- The Fleischer brothers patented the rotoscope technique in 1917, which was heavily used in this production

- Max Fleischer would often appear as himself in these shorts, creating a meta-narrative of animator and creation

- The track and field theme reflected the 1920s sports craze and Olympic fever of the era

- This short was released just before the major transition to sound films in 1928-1929

- Ko-Ko's character design evolved significantly from his first appearance in 1919 to this 1928 film

- The inkwell effect was achieved through careful animation combined with practical effects on the live-action footage

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'Koko's Field Daze' for its technical innovation and humor, with trade publications noting the seamless integration of live-action and animation. Reviewers specifically highlighted Ko-Ko's mischievous personality and the clever gags involving the track and field equipment. The film was recognized as continuing the high quality of the Out of the Inkwell series, which had built a reputation for technical excellence and entertainment value. Modern animation historians view the film as an important example of late-silent era animation, demonstrating the sophistication achieved before the transition to sound. Critics today appreciate the film's place in animation history and its role in developing techniques that would become standard in the industry.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1928 responded positively to 'Koko's Field Daze,' with Ko-Ko's antics proving particularly popular with both children and adults. The novelty of seeing an animated character interact with a real person continued to fascinate viewers, even as the technique became more familiar through the series. The sports-themed humor resonated with contemporary audiences during the height of the 1920s sports craze. Theater owners reported good attendance for the short when paired with feature films, as the Ko-Ko series had developed a loyal following. The film's success helped maintain the popularity of the Out of the Inkwell series through the challenging transition period to sound cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Winsor McCay's 'Gertie the Dinosaur'

- Early vaudeville comedy routines

- Contemporary sports films

- Silent era physical comedy

This Film Influenced

- Disney's 'Alice Comedies' series

- Warner Bros.' 'You Ought to Be in Pictures'

- Modern meta-fictional animated works

- Who Framed Roger Rabbit

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in archived collections and has been preserved through various film archives, including the Library of Congress and UCLA Film & Television Archive. Some versions may show deterioration typical of nitrate film from this era, but the core content remains accessible to researchers and animation enthusiasts.