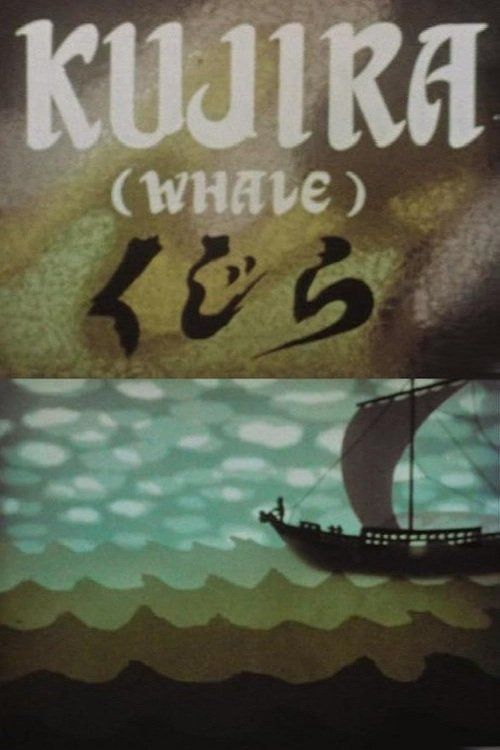

Kujira

Plot

Based on a traditional Japanese folk tale, 'Kujira' (The Whale) tells the story of a massive whale that terrorizes a coastal village by swallowing fishermen and villagers. The narrative follows a brave young man who ventures into the whale's belly to rescue the swallowed victims, including his beloved. Inside the whale's stomach, he discovers an entire underwater world where the swallowed people have adapted to their strange new environment. The protagonist must confront both the whale's internal defenses and his own fears to save his community and restore peace to the village. The film culminates in a dramatic escape that tests the limits of human courage and the bonds of community.

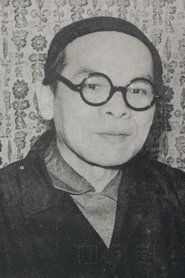

Director

About the Production

Kujira was created using paper cut-out animation (kami-e) techniques, a signature style of director Noburô Ôfuji. The film was produced on a very limited budget, forcing Ôfuji to innovate with materials and techniques. The animation was created by cutting out paper figures and moving them frame by frame, with the whale character requiring particularly complex manipulation to achieve fluid movement. The production team used traditional Japanese art aesthetics and color palettes to give the film an authentic cultural feel.

Historical Background

Kujira was produced in post-war Japan during a period of cultural renaissance and economic recovery. The mid-1950s saw Japan re-establishing its cultural identity and seeking international recognition through the arts. This film emerged during the early days of Japanese animation, predating the anime boom that would later make the industry globally dominant. The 1950s also marked Japan's re-engagement with the international community following years of isolation, and films like Kujira served as cultural ambassadors. The whale theme resonated deeply with Japanese audiences, as whaling had been an important part of Japanese coastal economies for centuries, though international attitudes toward whaling were beginning to shift during this period.

Why This Film Matters

Kujira represents a crucial bridge between traditional Japanese storytelling and modern animation techniques. The film helped establish Japan's reputation for innovative animation on the international stage, paving the way for later anime successes. Its use of paper cut-out animation preserved a distinctly Japanese artistic tradition while embracing contemporary cinematic technology. The film's success at the Venice Film Festival in 1956 was groundbreaking, being one of the first Japanese animated works to receive major international recognition. This achievement opened doors for other Japanese animators and helped establish the country's animation industry as a significant cultural export. The film also preserved an important Japanese folk tale that might otherwise have been lost to modernization.

Making Of

Noburô Ôfuji created 'Kujira' using his distinctive paper cut-out animation technique, which involved cutting figures from paper and photographing them frame by frame. The production was extremely labor-intensive, with Ôfuji often working alone or with a very small team. The whale character was particularly challenging to animate, requiring multiple layers of paper to create the illusion of bulk and movement. Ôfuji experimented with different types of paper, including translucent varieties, to achieve the underwater lighting effects. The film's soundtrack was created using traditional Japanese instruments to enhance the cultural authenticity. Ôfuji, who came from a family of artists, drew inspiration from both classical Japanese art and contemporary animation techniques he observed from international films.

Visual Style

The film's visual style is characterized by its distinctive paper cut-out animation technique, creating a unique aesthetic that combines two-dimensional and three-dimensional qualities. Ôfuji used layered paper to create depth and shadow effects, particularly effective in the underwater scenes inside the whale. The color palette draws heavily from traditional Japanese art, featuring muted earth tones contrasted with vibrant blues for the ocean scenes. The camera work is relatively simple but effective, using slow pans and zooms to guide the viewer's attention through the narrative. The animation achieves remarkable fluidity considering the limitations of paper cut-outs, especially in the whale's movements and the underwater sequences.

Innovations

Kujira pioneered several technical innovations in paper cut-out animation, particularly in creating the illusion of underwater movement and depth. Ôfuji developed new techniques for layering translucent paper to achieve lighting effects that simulated sunlight filtering through ocean water. The film also demonstrated innovative methods for animating large creatures, with the whale's movements being particularly sophisticated for the time and medium. The production team created custom tools for manipulating the paper figures, allowing for more precise and fluid motion than was typical in paper cut-out animation. These technical achievements influenced subsequent generations of animators working with alternative animation techniques.

Music

The film's score features traditional Japanese instruments including the shakuhachi (bamboo flute), koto (string instrument), and taiko drums. The music was composed to enhance the emotional impact of key scenes while maintaining cultural authenticity. Sound effects were created using both traditional methods and innovative techniques to simulate underwater environments and the whale's movements. The soundtrack minimalistic approach allows the visual storytelling to take center stage while providing emotional support to the narrative. The music incorporates elements of gagaku (ancient Japanese court music) to give the film a timeless, mythic quality.

Famous Quotes

Inside the belly of the beast, we found not death, but a new world of existence.

Courage is not the absence of fear, but the will to face it for those you love.

The whale, like the sea itself, gives life and takes it away – such is the balance of nature.

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic sequence where the whale first appears and swallows the fishermen, created with layered paper animation to achieve a sense of massive scale and power

- The protagonist's descent into the whale's mouth, using innovative camera angles and lighting effects to create a sense of entering another world

- The discovery of the underwater community inside the whale's stomach, featuring beautifully rendered paper cut-out figures adapting to their bizarre environment

- The climactic escape sequence, combining rapid animation with dynamic sound effects to create tension and excitement

Did You Know?

- The title 'Kujira' means 'whale' in Japanese, directly referencing the film's central creature

- Director Noburô Ôfuji was a pioneer of Japanese animation and particularly known for his paper cut-out animation style

- The film is based on a traditional Japanese folk tale about a whale that swallows people

- Despite its short runtime of only 13 minutes, the film took several months to create due to the meticulous frame-by-frame animation process

- Ôfuji used translucent paper and layered techniques to create depth and shadow effects in the underwater scenes

- The film was created during a period when Japanese animation was still developing its unique identity separate from Western influences

- Kujira was one of the first Japanese animated films to gain recognition at international film festivals

- The whale character was designed to be both terrifying and majestic, reflecting the complex relationship between Japanese coastal communities and these marine giants

- The film's color scheme was influenced by traditional Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints

- Ôfuji reportedly studied actual whale anatomy and movement to make the animated creature more realistic

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Kujira for its unique visual style and technical innovation. Western reviewers were particularly impressed by the paper cut-out animation technique, which differed significantly from the cel animation dominant in American and European productions. Japanese critics appreciated how Ôfuji successfully adapted traditional folk tales to the new medium of animation while maintaining cultural authenticity. Modern critics and film historians view Kujira as a masterpiece of early Japanese animation, often citing it as an example of how animation can preserve cultural heritage while pushing artistic boundaries. The film is frequently studied in animation history courses as an example of non-Western animation traditions.

What Audiences Thought

Initial Japanese audiences responded positively to Kujira, particularly appreciating its connection to familiar folk tales and traditional art styles. The film's short length made it popular as part of theater programs, often shown before feature films. International audiences at film festivals were fascinated by the unique animation style and cultural elements they hadn't seen before. Over the decades, the film has developed a cult following among animation enthusiasts and scholars of Japanese cinema. Modern audiences who discover the film often express surprise at how sophisticated and emotionally engaging a 13-minute animated short from 1955 can be.

Awards & Recognition

- Venice Film Festival - San Marco Silver Lion (1956)

- Mainichi Film Concours - Best Animation Film (1956)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Traditional Japanese folk tales

- Ukiyo-e woodblock prints

- Classical Japanese theater (Kabuki and Noh)

- Early Disney animation techniques

This Film Influenced

- Later works by Noburô Ôfuji

- Japanese animated folk tale adaptations

- Contemporary paper animation artists

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Kujira has been preserved by the National Film Center of Japan and is considered an important part of Japanese cinematic heritage. The film has undergone digital restoration to ensure its survival for future generations. Original prints and negatives are maintained in climate-controlled archives. The film is occasionally screened at film festivals and museum retrospectives dedicated to animation history. Some restoration work was needed to repair damage to the original paper elements used in the animation, but the film remains largely intact.