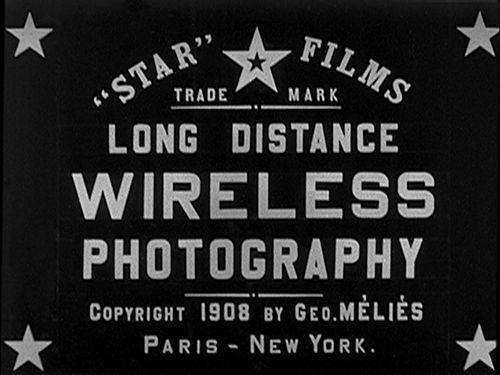

Long Distance Wireless Photography

Plot

In Georges Méliès's whimsical 1908 fantasy, an elderly couple enters a photography studio filled with elaborate, fantastical machinery. The bearded proprietor, played by Méliès himself, demonstrates his revolutionary invention by starting the machines whirring and projecting a painting of three women onto a large screen, which magically come to life to the customers' amazement. The elderly woman volunteers first, sitting in a special chair where her image is projected, revealing her cheerful and good-natured personality through her laughing portrait. When her husband takes his turn, however, the machine exposes a completely different and darker side of his character, causing him to become enraged. The man's furious reaction threatens to destroy the proprietor's marvelous inventions in this early exploration of technology revealing hidden truths about human nature.

Director

About the Production

This film was shot in Méliès's glass-walled studio in Montreuil, using his signature theatrical sets and painted backdrops. The film employed multiple exposure techniques and substitution splices to create the magical effects of the projections coming to life. Méliès used his own patented mechanical devices to simulate the elaborate machinery, many of which were repurposed from his earlier films. The production followed Méliès's typical method of filming everything in a single take with stationary camera, relying on stage magic techniques adapted for cinema.

Historical Background

Released in 1908, 'Long Distance Wireless Photography' emerged during a pivotal period in early cinema history. This was the year when the Motion Picture Patents Company (often called the Edison Trust) was formed in America, attempting to monopolize film production and distribution. In France, where Méliès worked, cinema was transitioning from novelty attraction to narrative art form. The film reflected contemporary fascination with new technologies, particularly wireless telegraphy following Guglielmo Marconi's successful transatlantic radio transmissions in 1901-1907. Méliès's work represented the older theatrical tradition of cinema, which was being challenged by newer, more realistic filmmaking styles emerging from directors like the Lumière brothers and D.W. Griffith. 1908 was also the year before Méliès would face his greatest professional crisis, when his films were illegally duplicated and distributed in America by competitors, contributing to his eventual financial ruin. This film thus represents both the height of Méliès's creative powers and the beginning of the end of his dominance in the film industry.

Why This Film Matters

As one of Georges Méliès's later works, 'Long Distance Wireless Photography' holds significant importance in the history of cinema as an example of early narrative science fiction. The film demonstrates Méliès's evolution from simple trick films to more complex stories exploring themes of technology and human nature. It represents a crucial transitional period in cinema when filmmakers were beginning to explore the psychological and philosophical implications of new technologies, rather than merely showcasing their magical possibilities. The film's concept of a machine revealing inner character prefigured countless later science fiction works exploring similar themes. Méliès's innovative use of multiple exposure and substitution splices in this film influenced generations of special effects artists. The work also serves as a valuable document of early 20th-century attitudes toward technology and the belief in its power to reveal hidden truths. Today, the film is studied by film scholars as an example of how early cinema began to move beyond spectacle to explore more sophisticated narrative and thematic concerns, paving the way for the narrative cinema that would dominate the following decades.

Making Of

The making of 'Long Distance Wireless Photography' exemplified Méliès's masterful blend of theatrical stagecraft and cinematic innovation. In his glass studio in Montreuil, Méliès constructed elaborate sets that resembled a fantastical laboratory, filled with props designed to look like advanced photographic equipment. The film's magical effects were achieved through multiple exposure techniques, where Méliès would film the same piece of film multiple times with different elements added each time. The projection scenes required careful timing and precise camera work, with actors having to perform in synchronization with pre-filmed elements. Fernande Albany, who had worked extensively with Méliès, would have been intimately familiar with his exacting requirements for timing and performance. The production likely took only a day or two of actual filming, as was typical for Méliès's short films, though the preparation of sets and props would have taken much longer. The film was created during a period when Méliès was increasingly focusing on narrative-driven content rather than pure spectacle, reflecting his adaptation to changing audience tastes in the evolving cinema landscape.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Long Distance Wireless Photography' exemplifies Méliès's distinctive approach to filmmaking, which was heavily influenced by his background in theater. The film was shot with a stationary camera positioned to capture the entire stage, much like a theater audience's view of a performance. This single-camera, wide-shot approach was typical of Méliès's work and contrasted with the more dynamic camera movements being developed by other filmmakers of the era. The visual style relied heavily on elaborate painted backdrops and theatrical sets that created the illusion of a fantastical photography studio. Méliès employed sophisticated multiple exposure techniques to create the magical projection effects, carefully layering different images to achieve the illusion of paintings coming to life. The film's lighting was designed to enhance the theatrical atmosphere, with strong directional lighting creating dramatic shadows and highlighting the magical elements of the machinery. Color was likely added through hand-coloring techniques for special releases, with each frame individually painted to create vibrant, dreamlike images that enhanced the film's fantastical quality.

Innovations

'Long Distance Wireless Photography' showcased several of Georges Méliès's most sophisticated technical innovations for its time. The film's most notable achievement was its masterful use of multiple exposure techniques to create the illusion of projections coming to life. Méliès accomplished this by rewinding the film and exposing it multiple times with different elements, creating seamless composite images that appeared magical to contemporary audiences. The substitution splices used during the transformation scenes were executed with remarkable precision, demonstrating Méliès's mastery of early editing techniques. The elaborate machinery featured in the film was an impressive feat of practical effects, combining real mechanical elements with theatrical props to create convincing-looking fantastical equipment. Méliès's use of painted backdrops and forced perspective created the illusion of a much larger space than his studio actually provided. The film also demonstrated advanced understanding of timing and synchronization in the projection scenes, where actors had to perform in perfect coordination with pre-filmed elements. These technical achievements represented the culmination of Méliès's decade of experimentation with cinematic effects and influenced the development of visual effects in cinema for generations to come.

Music

As a silent film from 1908, 'Long Distance Wireless Photography' was originally presented without a synchronized soundtrack. During its initial theatrical run, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra performing appropriate selections to match the on-screen action. The musical accompaniment would have ranged from whimsical tunes during the magical demonstrations to more dramatic music during the man's angry outburst. Some theaters might have used popular songs of the era or classical pieces that fit the mood of different scenes. Méliès often provided detailed musical suggestions with his films to guide theater musicians, though specific recommendations for this film are not documented. Modern presentations of the film typically feature newly composed scores or carefully selected period-appropriate music. Contemporary restorations sometimes feature original-style piano accompaniment or orchestral arrangements that attempt to recreate the experience of early 20th-century cinema exhibition. The absence of dialogue in the film made the visual storytelling and musical accompaniment particularly important for conveying the narrative and emotional content to audiences.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue exists as this is a silent film, but intertitles would have included: 'The Wonderful Wireless Photography Studio', 'Behold the Magic of Science!', 'The Truth Revealed!'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where the elderly couple enters the fantastical photography studio filled with elaborate machinery and strange devices

- The magical moment when the proprietor projects a painting of three women onto the screen and they begin to move and dance

- The woman's turn in the special chair, where her projection reveals her cheerful, laughing nature

- The climactic scene where the man's projection exposes his hidden angry character, causing him to rage against the machine

- The final chaotic scene where the enraged man threatens to destroy all the marvelous inventions

Did You Know?

- This film was released under the French title 'Photographie électrique à distance' and distributed by Méliès's Star Film Company as catalog number 1251-1254.

- The film showcases Méliès's fascination with technology and its potential to reveal hidden truths, a recurring theme in his work.

- Fernande Albany, who plays the elderly woman, was one of Méliès's most frequent collaborators, appearing in over 20 of his films.

- The elaborate machinery in the film was largely constructed from theatrical props and stage equipment that Méliès had accumulated from his previous career as a magician.

- This film was part of Méliès's later period (1907-1912) when he was facing increasing competition from other filmmakers and struggling financially.

- The film's concept of a machine revealing inner character was quite advanced for its time, predating similar themes in later science fiction.

- Like many of Méliès's films, this one was hand-colored frame by frame for special releases, though most surviving copies are black and white.

- The film was likely inspired by the growing public fascination with wireless technology following Marconi's radio transmissions in the early 1900s.

- Méliès often played the inventor or magician character in his own films, using his theatrical background to create memorable performances.

- This film represents one of Méliès's more sophisticated narratives, moving beyond simple trick films to explore character psychology.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'Long Distance Wireless Photography' in 1908 is difficult to document, as film criticism was still in its infancy and most reviews appeared in trade papers rather than general publications. However, Méliès's films of this period were generally well-received by audiences who appreciated his imaginative storytelling and magical effects. The film was likely praised for its clever concept and elaborate sets, which were hallmarks of Méliès's style. Modern critics and film historians view the work as an important example of Méliès's more mature narrative style, noting how it combines his signature visual effects with a more sophisticated exploration of character and theme. Scholars particularly appreciate how the film reflects early 20th-century anxieties and fascinations with technology, serving as a precursor to later science fiction cinema. The film is often cited in discussions of Méliès's influence on the development of visual effects and his role in establishing cinema as a medium for fantastic storytelling rather than just documentary realism.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1908 generally responded positively to Méliès's films, which were popular attractions at fairgrounds and early movie theaters. 'Long Distance Wireless Photography' likely delighted viewers with its combination of humor, magic, and technological wonder. The film's accessible premise of a machine revealing hidden character would have resonated with contemporary audiences fascinated by new inventions like the telephone and wireless telegraphy. The visual spectacle of the projections coming to life would have been particularly impressive to early cinema-goers who were still discovering the possibilities of the medium. However, by 1908, audiences were beginning to demand more realistic narratives, and some may have found Méliès's theatrical style somewhat dated compared to newer, more naturalistic films. Despite this, Méliès retained a loyal following, and films like this one continued to find appreciative audiences, particularly among those who enjoyed the magical and fantastical elements that made his work distinctive. Today, the film is primarily viewed by film enthusiasts and scholars who appreciate its historical significance and Méliès's pioneering contributions to cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic and theatrical traditions

- Early scientific discoveries about electricity and wireless transmission

- Georges Méliès's background as a magician

- Contemporary fascination with new technologies

- Popular science fiction literature of the early 1900s

- Comedic traditions of French theater

- The work of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells

This Film Influenced

- Later science fiction films about technology revealing character

- Comedy films about inventions gone wrong

- Early narrative films exploring psychological themes

- Subsequent films using projection as a metaphor

- Movies about the dangers of technological revelation

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in archives and is considered preserved, though like many Méliès films, it exists in incomplete form. Copies are held at the Cinémathèque Française and other film archives. Some versions show signs of deterioration common to films of this era. The film has been restored by various institutions, including the Méliès family and film preservation organizations. Hand-colored versions, if they exist, are extremely rare. Most available versions are black and white and may be missing frames or show damage from age. The film is part of the larger effort to preserve Méliès's body of work, much of which was lost or destroyed during World War I and in the decades following.