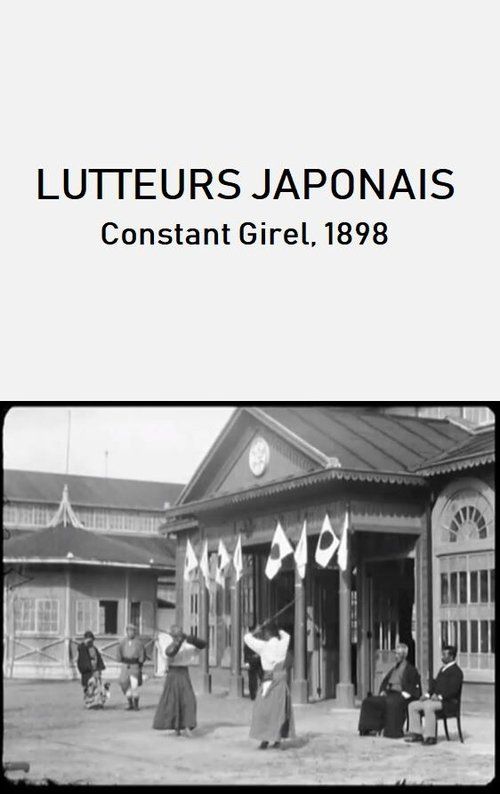

Lutteurs japonais

Plot

This pioneering documentary short captures two Japanese fighters dressed in traditional martial arts attire as they engage in a kendo tournament. The film showcases the precise movements and ceremonial aspects of Japanese sword fighting, with the performers demonstrating various techniques and stances characteristic of kendo practice. The camera remains stationary, observing the fighters as they move through their choreographed sequence, offering Western audiences one of their earliest glimpses into Japanese martial arts culture. The brief but significant recording preserves not just the physical movements but also the traditional costumes and equipment used in these ceremonial combat demonstrations.

Director

About the Production

This film was shot by Constant Girel during his expedition to Japan as one of the Lumière Company's traveling cinematographers. The production required transporting heavy and cumbersome camera equipment to Japan, which was quite remarkable for 1898. The filming likely took place outdoors due to lighting limitations of early cameras, and the fighters were probably local martial artists hired specifically for this demonstration. The entire sequence would have been filmed in one continuous take, as editing capabilities were virtually non-existent at this time.

Historical Background

This film was created during the Meiji Restoration period in Japan (1868-1912), when Japan was rapidly modernizing and opening up to Western influence after centuries of isolation. The late 1890s marked the dawn of cinema worldwide, with the Lumière brothers having held their first public screening just three years earlier in 1895. For Western audiences, films like this provided their first moving images of Japan, a country that remained mysterious and exotic to most Europeans. The film also captures a transitional moment in Japanese martial arts, as traditional practices were being codified and modernized. The documentation of kendo at this specific moment is historically valuable, as it shows the art form before many of the standardizations that would occur in the 20th century.

Why This Film Matters

Lutteurs japonais represents a crucial milestone in both cinematic and cultural history. As one of the earliest films documenting Japanese culture, it served as an important bridge between East and West during a period of increasing global awareness. The film helped establish the documentary genre and demonstrated cinema's potential as an ethnographic tool. For Japanese culture, it preserves a rare visual record of martial arts practice during a period of significant transition. The film also exemplifies the early 20th century fascination with exotic cultures that would influence both cinema and popular culture for decades. Its existence proves that international film documentation began almost immediately after cinema's invention, showing the global reach of this new medium from its earliest days.

Making Of

Constant Girel's journey to Japan in 1898 was part of the Lumière brothers' ambitious plan to capture authentic footage from around the world to show to European audiences. Girel had to transport the heavy cinématographe device by ship and navigate the cultural and linguistic barriers of working in Japan during the Meiji period. The fighters featured in the film were likely martial arts practitioners who agreed to demonstrate their skills for this new technology. The filming process required the performers to maintain their movements within the limited frame of the camera and under the challenging lighting conditions of early film equipment. Girel would have had to hand-crank the camera throughout the entire sequence, maintaining a consistent speed to ensure proper exposure.

Visual Style

The cinematography is characteristic of Lumière Company productions from this era - stationary camera, natural lighting, and a single continuous take. The camera position was carefully chosen to capture the full range of the fighters' movements within the frame. The composition shows both fighters in their entirety, allowing viewers to appreciate their traditional costumes and the full execution of their techniques. The black and white imagery creates stark contrasts that emphasize the fighters' movements against the background. Given the technical limitations of 1898, the clarity of the image is remarkable, though the frame rate would have been inconsistent by modern standards due to hand-cranking. The fixed perspective actually works in the film's favor, creating a sense of observing a traditional demonstration or ceremony.

Innovations

The primary technical achievement of this film is simply its existence - capturing moving images in Japan in 1898 required overcoming enormous logistical and technical challenges. The transport of the cinématographe to Japan and successful operation in field conditions represents a significant accomplishment for early cinema technology. The film demonstrates the portability and reliability of Lumière equipment, which could function in diverse global locations. The clear capture of rapid martial arts movements also showcases the capabilities of early film stock and cameras to document action sequences, which would influence the future development of action cinema.

Music

This film was produced during the silent era and would have been accompanied by live music during exhibition. The type of musical accompaniment would have varied depending on the venue and could have ranged from a single pianist to a small orchestra. Some exhibitors might have used Japanese-inspired music to enhance the exotic atmosphere, while others would have used whatever was available. The original exhibition would not have had synchronized sound, and any sounds of the fighters' movements or equipment would have been imagined by the audience or suggested by the musical accompaniment.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where both fighters bow to each other in traditional martial arts etiquette before beginning their demonstration, capturing the ceremonial respect inherent in Japanese martial arts culture

Did You Know?

- This is one of the earliest films ever made in Japan, captured just three years after the invention of cinematography

- Constant Girel was one of the Lumière brothers' most trusted cinematographers, sent on expeditions around the world

- The film predates the establishment of Japan's own film industry by several years

- Kendo itself was still evolving as a modern martial art during this period, having been formalized only in the late 19th century

- The fighters likely performed specifically for the camera, as actual tournaments would have been too chaotic and dangerous for early filming equipment

- This film represents some of the earliest moving image documentation of Japanese culture available to Western audiences

- The original film was shot on 35mm film using the Lumière cinématographe, which also served as the projector and developer

- Only a few copies of this film are known to exist today, making it an extremely rare piece of cinema history

- The film was part of a series of Japanese-themed shorts that Girel produced during his time in the country

- At 35 seconds, this was actually considered a substantial length for films of this era

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of this film would have been limited to trade publications and exhibition catalogs, as formal film criticism was still in its infancy. The film was likely praised for its exotic subject matter and the novelty of capturing Japanese martial arts on film. Modern film historians and archivists consider it an invaluable document of early cinema and Japanese cultural history. Critics today appreciate it not for its technical merits but for its historical significance as one of the earliest moving images of Japan and as an example of the Lumière Company's global documentation efforts. The film is frequently cited in academic works about early documentary cinema and cross-cultural film representation.

What Audiences Thought

When first exhibited, Lutteurs japonais would have fascinated European audiences who had likely never seen moving images of Japan or Japanese people. The film's novelty factor alone would have ensured positive reception, as any film from this exotic location would have been a major attraction. Audiences of the time were captivated by the Lumière Company's actualités (actuality films) showing real scenes from around the world. The martial arts demonstration would have been particularly entertaining due to its dynamic movement and cultural unfamiliarity. Modern audiences viewing the film in archives or retrospectives appreciate it primarily for its historical value rather than entertainment content, though martial arts enthusiasts find it fascinating for its documentation of early kendo practice.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Lumière actualité films

- Early ethnographic documentation

- Travelogue films

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent martial arts documentaries

- Japanese cultural films

- Early 20th century ethnographic cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in film archives, particularly at the Lumière Institute in France. While the original nitrate film stock would have been highly unstable and dangerous, preservation efforts have ensured its survival. The film exists in restored digital formats and is occasionally screened at film festivals and museum exhibitions focusing on early cinema. Some degradation is likely present due to the age of the material, but it remains viewable and historically valuable.