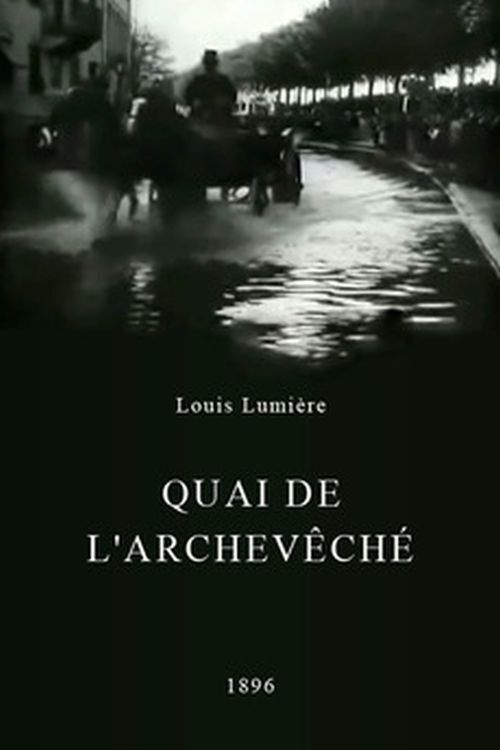

Lyon: Quai de l'Archevêché

Plot

This actuality film captures a dramatic moment in Lyon's history as the Saône river overflows its banks during the first week of November 1896. The camera observes the flooded Quai de l'Archevêché (Archbishop's Quay) where water has inundated the streets, creating unusual scenes of boats navigating where pedestrians normally walk. Local residents are shown dealing with the aftermath of the flood, with some using small boats to move through the waterlogged streets while others observe from higher ground. The film serves as both a documentary record of a natural disaster and an early example of newsreel-style filmmaking, capturing the real-time impact of the flooding on urban life in late 19th century France.

Director

About the Production

Filmed using the Lumière Cinématographe, which served as both camera and projector. The film was shot during the actual flood events of November 1896, making it one of the earliest examples of documentary news coverage. The camera was likely positioned at an elevated position to capture the full scope of the flooding, demonstrating the Lumière brothers' understanding of composition even in documentary situations. This film was part of the Lumière brothers' extensive catalog of actualités that documented everyday life and newsworthy events.

Historical Background

This film was created during the very birth of cinema, less than a year after the Lumière brothers' first public screening on December 28, 1895. 1896 was a pivotal year when moving pictures transitioned from technological novelty to emerging art form. The film was made during a period of rapid industrialization and urbanization in France, with Lyon being a major industrial center known for its silk production. The Saône river floods of November 1896 were significant enough to warrant documentation, reflecting the growing importance of visual journalism. This period also saw the development of film as a medium for documenting current events, predating the establishment of newsreel companies by several years. The film captures a moment when Lyon, like many European cities, was dealing with the challenges of urban infrastructure and natural disasters, issues that remain relevant today.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the earliest documentary films, 'Lyon: Quai de l'Archevêché' holds immense cultural significance for several reasons. It represents the birth of documentary cinema and news reporting on film, establishing a precedent for visual journalism that would evolve throughout the 20th century. The film demonstrates how quickly early filmmakers recognized cinema's potential beyond mere entertainment, using it to document real events and preserve moments of history. It also reflects the Lumière brothers' philosophy of cinema as 'the recreation of reality,' contrasting with Georges Méliès' more fantastical approach to filmmaking. The film serves as an invaluable historical document, preserving a visual record of Lyon's urban landscape and the challenges faced by its residents in the late 19th century. Its survival allows modern audiences to witness both the infancy of cinema and a moment in Lyon's history, bridging more than a century of technological and social change.

Making Of

The filming of 'Lyon: Quai de l'Archevêché' represents a significant moment in early cinema history, as it demonstrates the Lumière brothers' commitment to capturing real events as they happened. The cameraman, likely one of the Lumière brothers' trained operators, had to quickly respond to the flooding situation and transport the bulky Cinématographe equipment to an optimal vantage point. This required considerable effort given the flooded conditions and the primitive nature of film equipment in 1896. The film was shot using 35mm film with the Cinématogratograph's hand-crank mechanism, requiring the operator to maintain a consistent cranking speed while framing the shot. The location choice was strategic - the Quai de l'Archevêché offered a clear view of both the flooding and human response to it. This film was part of the Lumières' strategy to create a comprehensive catalog of views that would appeal to audiences' curiosity about the world around them, while also demonstrating the new medium's ability to document reality.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Lyon: Quai de l'Archevêché' exemplifies the Lumière brothers' straightforward, observational style. The film was shot using a fixed camera position, typical of early actualités, with careful attention to composition to capture both the flooding and human activity within the frame. The camera was likely placed at an elevated vantage point to provide a comprehensive view of the scene, demonstrating early understanding of perspective and scale in moving images. The black and white imagery, characteristic of the era, creates a stark contrast between the dark floodwaters and the lighter architectural elements. The single continuous take, lasting less than a minute, reflects the technical limitations of early film equipment while also creating an unmediated view of the event. The cinematography prioritizes clarity and documentation over artistic flourish, embodying the Lumière philosophy of cinema as a window onto reality.

Innovations

The film represents several important technical achievements of early cinema. It was shot using the Lumière Cinématographe, a revolutionary device that combined camera, projector, and developer in one unit, making it more portable and practical than earlier inventions. The use of 35mm film with perforations established a standard that would dominate the industry for decades. The film demonstrates early mastery of exposure techniques, necessary for capturing outdoor scenes with consistent image quality. The ability to quickly respond to and document a current event like a flood showed the increasing portability and efficiency of film equipment. The film's survival also testifies to the durability of early celluloid stock and the effectiveness of preservation methods, though many films from this period have been lost.

Music

As was standard for films of 1896, 'Lyon: Quai de l'Archevêché' was originally presented as a silent film without any synchronized soundtrack. During early cinema exhibitions, musical accompaniment was typically provided live by pianists, organists, or small ensembles who would improvise or play appropriate music to enhance the viewing experience. For a film depicting a flood, the accompaniment might have included dramatic or somber pieces to match the serious nature of the subject. Some venues might have used sound effects created by staff members to enhance the illusion of reality. The lack of recorded sound was due to technological limitations of the period, with synchronized sound not becoming commercially viable until the late 1920s.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening shot showing the flooded Quai de l'Archevêché with boats navigating through streets normally used by pedestrians, creating a surreal vision of urban life disrupted by natural forces

Did You Know?

- This is one of the earliest examples of disaster documentary filmmaking in cinema history

- The film was shot during an actual flood event, making it an early example of what would later be called 'on-the-spot' news reporting

- The Lumière brothers' cameraman had to transport the heavy Cinématographe equipment through potentially dangerous conditions to capture this footage

- This film was part of a series of actualités the Lumières produced showing various aspects of life in Lyon and other French cities

- The Quai de l'Archevêché is located near the historic center of Lyon and has been an important riverside location for centuries

- Early audiences were fascinated by films showing real events they might have read about in newspapers

- This film demonstrates how quickly the Lumières recognized cinema's potential as a documentary medium

- The flood of 1896 was one of several significant floods that affected Lyon throughout its history due to its location at the confluence of the Rhône and Saône rivers

- Like many early Lumière films, this was likely shown alongside other short films in a program lasting about 15-20 minutes

- The film's survival makes it an invaluable historical document of both early cinema and 19th century urban life

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of early Lumière films like 'Lyon: Quai de l'Archevêché' was generally positive, with audiences and critics marveling at the technology's ability to capture and reproduce reality. French newspapers of the period often described the Lumière exhibitions as miraculous and revolutionary. Modern film historians and critics view this film as an important early example of documentary filmmaking, praising its historical value and the Lumière brothers' instinct for capturing newsworthy events. The film is frequently cited in scholarly works about early cinema as evidence of how quickly filmmakers recognized the documentary potential of the new medium. Critics today appreciate the film not just for its technical achievement but also for its unvarnished view of urban life and disaster response in the 19th century.

What Audiences Thought

Early audiences were reportedly fascinated by films showing real events and places they recognized or had read about in newspapers. 'Lyon: Quai de l'Archevêché' would have been particularly compelling to local Lyon residents who might have experienced or heard about the flood. The film's ability to capture a recent, newsworthy event demonstrated the immediate relevance of cinema to everyday life. Audience reactions to early Lumière films often included expressions of disbelief and wonder at the moving images, with some viewers reportedly ducking when seeing objects appear to move toward the camera. The film's documentary nature appealed to audiences' curiosity about the world and their desire to see reality reproduced on screen, a fascination that helped establish cinema as a popular entertainment medium.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Lumière brothers' philosophy of capturing reality

- Early photography traditions of documentary

- 19th century journalistic practices

- The tradition of actualités in early French cinema

This Film Influenced

- Later Lumière actualités depicting news events

- Early newsreel films

- Documentary traditions in French cinema

- The development of disaster filmmaking

- Modern documentary approaches to natural disasters

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Lumière Institute's collection in Lyon and is considered one of the surviving examples of early Lumière actualités. It has been digitized and restored as part of ongoing efforts to preserve early cinema heritage. The film exists in various film archives worldwide and is occasionally shown in retrospectives of early cinema. Its survival makes it an important historical document of both early filmmaking techniques and late 19th century urban life.