Magic Dice

Plot

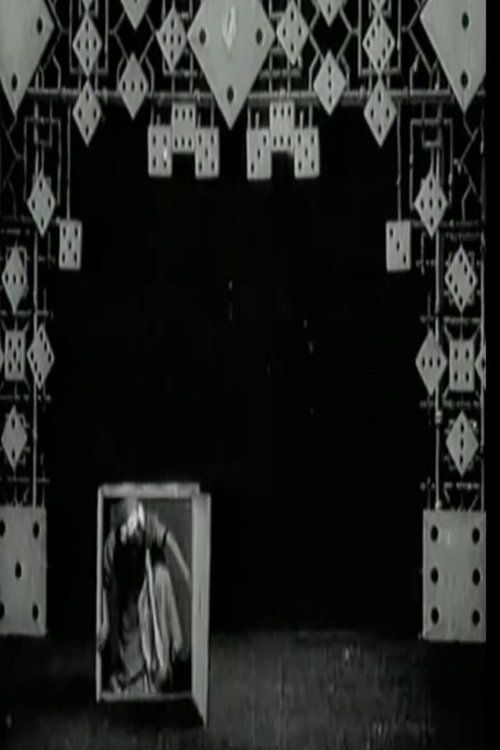

In this early fantasy trick film, a magician produces a set of dice that magically multiply and transform through a series of ingenious special effects. The dice appear and disappear, change size, and perform impossible movements that defy the laws of physics. The magician, played by Segundo de Chomón himself or possibly Julienne Mathieu in disguise, manipulates the dice with seemingly supernatural abilities. The film showcases a progression of increasingly complex visual tricks, each more impressive than the last, demonstrating the technical mastery of early cinema special effects. The performance concludes with a spectacular finale where the dice transform into other objects or multiply to fill the screen.

Director

Cast

About the Production

This film was created using multiple exposure techniques, substitution splices, and meticulous matte work. The colored version was produced using Pathécolor stencil process, a labor-intensive technique where each frame was hand-colored by stenciling. The dice effects required precise timing and coordination between multiple takes.

Historical Background

1908 was a pivotal year in early cinema, marking the transition from simple actualities to more complex narrative and trick films. The film industry was rapidly evolving, with Pathé Frères establishing itself as the dominant global film producer. This period saw the emergence of specialized film genres, with fantasy and trick films becoming extremely popular. The technology of cinema was advancing quickly, with improvements in camera stability, film stock quality, and editing techniques. De Chomón's work represents the pinnacle of pre-World War I European cinema, before the industry would be disrupted by the war and Hollywood's rise to dominance.

Why This Film Matters

'Magic Dice' represents an important milestone in the development of cinematic special effects and visual storytelling. It demonstrates how early filmmakers pushed the boundaries of what was possible with the limited technology available, creating wonder and spectacle for audiences who had never seen such visual magic before. The film is part of the tradition of stage magic translated to cinema, helping establish the movie theater as a place of wonder and illusion. Its preservation and study today provides insight into the technical ingenuity of early filmmakers and the evolution of cinematic language. The film also illustrates the international nature of early cinema, with a Spanish director working for a French company creating films for global distribution.

Making Of

The creation of 'Magic Dice' required extensive planning and technical innovation. De Chomón and his team had to carefully choreograph each trick effect, often requiring multiple takes that were then combined through optical printing. The dice multiplication sequence was particularly challenging, as it needed precise timing to create the illusion of objects appearing from nowhere. Julienne Mathieu, besides acting, likely assisted with the hand-coloring process, which was typically done by women in the Pathé studios. The film was shot on the Pathé studio sets in Paris, using the company's patented camera equipment. Each special effect had to be accomplished in-camera or through laboratory work, as there was no post-production digital manipulation available in 1908.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Magic Dice' demonstrates the sophisticated understanding of camera work and special effects that de Chomón possessed. The film uses static camera positioning typical of the era, but within this constraint creates dynamic visual effects through multiple exposures and substitution splices. The lighting is carefully controlled to ensure the special effects remain convincing, with particular attention paid to maintaining consistent illumination across the different takes that would be combined. The colored version showcases the Pathécolor stencil process at its finest, with vibrant, carefully applied colors that enhance the magical quality of the tricks.

Innovations

'Magic Dice' showcases several pioneering technical achievements in early cinema. The film demonstrates advanced mastery of multiple exposure techniques, allowing objects to appear and disappear seamlessly. The substitution splices used for the transformations are remarkably smooth for the period. The Pathécolor stencil coloring process represents one of the most sophisticated color techniques available before the advent of true color film. The precise timing required for the dice effects shows an advanced understanding of cinematic rhythm and editing. The film also demonstrates early matte work techniques that would become fundamental to special effects cinema.

Music

As a silent film, 'Magic Dice' would have been accompanied by live music during its theatrical exhibition. Typical accompaniment might have included piano or organ music, with the performer choosing pieces that matched the magical and mysterious mood of the film. Some theaters might have used compiled cue sheets suggesting specific musical pieces for trick films. The rhythm and pacing of the effects would have influenced the musical accompaniment, with faster sequences matched by more energetic music. No original score exists, as was standard for films of this period.

Famous Quotes

'This is not only a colored film of great beauty, but one showing a series of clever trick pictures in which great ingenuity on the part of the operator is exhibited.' - Contemporary film catalog description

Memorable Scenes

- The sequence where dice multiply rapidly across the screen, creating a cascade of magical objects that defies physical logic and showcases the technical mastery of early special effects work

Did You Know?

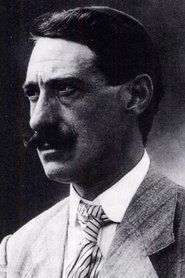

- Segundo de Chomón was often called 'the Spanish Méliès' due to his mastery of trick films and special effects

- Julienne Mathieu, who appears in the film, was de Chomón's wife and frequent collaborator

- The film was part of Pathé's popular series of trick films that captivated early cinema audiences

- The colored version utilized the Pathécolor process, which could take weeks to complete for a short film

- De Chomón pioneered many special effects techniques that would become standard in cinema

- The dice effects were achieved through careful editing and multiple exposures, not digital manipulation

- This film was distributed internationally and shown in theaters across Europe and America

- The production required dozens of identical dice to create the multiplication effects

- De Chomón worked closely with Georges Méliès earlier in his career and learned many techniques from him

- The film survives in both black and white and colored versions in various film archives

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its technical ingenuity and visual beauty. Trade publications of the era noted the 'clever trick pictures' and 'great ingenuity' displayed in the production. The film was particularly admired for its smooth execution of seemingly impossible effects. Modern film historians recognize 'Magic Dice' as an exemplary work of early cinema special effects, often citing it in studies of pre-1910 fantasy films. Critics today appreciate it both as a technical achievement and as a charming example of early cinematic wonder.

What Audiences Thought

Early cinema audiences were captivated by 'Magic Dice' and similar trick films, which offered a form of visual entertainment impossible to achieve on the live stage. The film was popular in both European and American theaters, where it was often featured as part of mixed bills alongside other short subjects. Audiences marveled at the impossible transformations and the smooth execution of the special effects. The colored version was particularly prized by exhibitors as it commanded higher ticket prices. The film's brief runtime made it ideal for the varied programming formats of early movie theaters.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès' trick films

- Stage magic traditions

- Pathé's series of fantasy films

- Early cinema actualities

This Film Influenced

- Later trick films by various directors

- Early Disney animation

- Contemporary special effects films

- Modern magic-themed cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in several archives including the Cinémathèque Française and the Library of Congress. Both black and white and colored versions survive. The film has been restored and is available through various film preservation organizations and specialty distributors.