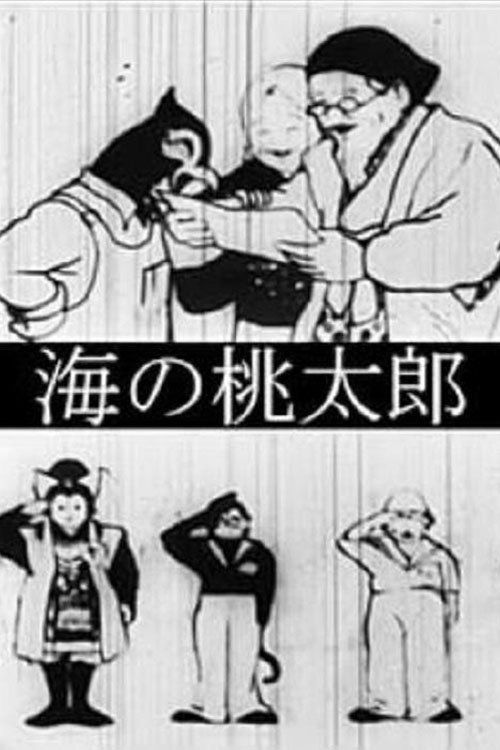

Momotaro's Underwater Adventure

Plot

In this early Japanese animated short, the legendary folk hero Momotaro (Peach Boy) embarks on an extraordinary underwater adventure. After emerging from his giant peach birthplace, Momotaro discovers a magical underwater kingdom threatened by evil forces. With his loyal animal companions - a dog, monkey, and pheasant - he dives beneath the waves to confront underwater demons and restore peace to the aquatic realm. The film combines traditional Japanese folklore with imaginative underwater settings, showcasing early animation techniques to bring this fantastical journey to life. Momotaro uses his supernatural strength and courage to battle sea monsters and rescue the underwater kingdom's inhabitants.

Director

About the Production

Created using cut-out animation techniques common in early Japanese anime, with hand-painted backgrounds and characters cut from paper. The film was made during a period when Japanese animators were heavily influenced by Western cartoons but beginning to develop their own distinctive style. The underwater sequences required innovative animation techniques for the time, including layered cels to create depth and movement effects.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1932, during a period of significant political and cultural change in Japan. The early 1930s saw the rise of militarism and increasing nationalism, which would later influence Japanese media content. However, this early animated short predates the most intense period of wartime propaganda. The Japanese animation industry was still in its infancy, with most studios being small operations that produced short films for theatrical exhibition. Western animation, particularly from Disney and Fleischer Studios, was extremely popular in Japan and heavily influenced early Japanese animators. This period also saw the beginning of the transition from silent to sound films, though many short animations continued to be produced without synchronized sound due to budget constraints.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important milestone in the development of Japanese anime as a distinct art form. As one of the early animated adaptations of traditional Japanese folklore, it demonstrates how Japanese animators began to move beyond simply imitating Western styles to create content rooted in their own cultural heritage. The choice of Momotaro as a protagonist is particularly significant, as this character would later be used in wartime propaganda films, most notably in 'Momotaro's Divine Sea Warriors' (1945), Japan's first feature-length animated film. The underwater setting shows early Japanese animators' willingness to experiment with fantastical elements and expand beyond traditional storytelling boundaries.

Making Of

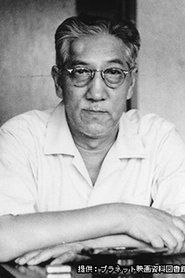

The production of 'Momotaro's Underwater Adventure' took place during a formative period in Japanese animation history. Director Yasuji Murata, working with limited resources and early animation technology, had to innovate to create the underwater effects. The animation team likely used multiple layers of painted glass and paper cut-outs to simulate the underwater environment, creating depth through careful layering and movement. Character designs would have been influenced by both traditional Japanese illustration styles and Western animation conventions of the era. The voice work, if any, would have been performed live during screenings, as synchronized sound technology was still expensive and not widely available for short films in Japan at this time.

Visual Style

The film utilized early animation techniques including cut-out animation and possibly some cel animation. The underwater sequences required innovative approaches to create the illusion of being submerged, including the use of transparent overlays and careful timing of character movements to simulate water resistance. Backgrounds were likely hand-painted with attention to traditional Japanese artistic aesthetics, while character designs showed the influence of both Japanese illustration styles and Western animation conventions of the era.

Innovations

For its time, the film represented several technical achievements in Japanese animation. The underwater effects were particularly innovative, requiring animators to develop new techniques for simulating movement through water. The use of multiple layers to create depth in the underwater scenes was advanced for early 1930s animation. The film also demonstrated early attempts at creating fluid character movement and expressive animation within the technical constraints of cut-out animation techniques.

Music

The film was likely released as a silent short with live musical accompaniment provided by theater musicians. The music would have been a mix of traditional Japanese melodies and Western-style orchestral pieces, reflecting the cultural blend common in Japanese cinema of the period. Sound effects would have been created live by theater staff using various props and techniques. If any synchronized sound was used, it would have been limited to basic music or effects rather than dialogue.

Famous Quotes

No documented dialogue quotes are available from this silent film

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Momotaro emerging from the giant peach, the transformation of Momotaro's animal companions into underwater adventurers, the climactic battle with the sea demons in their underwater castle, the peaceful restoration of the underwater kingdom

Did You Know?

- This is one of the earliest surviving examples of Japanese animation featuring the Momotaro character, who would become one of the most frequently adapted figures in Japanese animation history

- Director Yasuji Murata was a pioneer of Japanese animation who worked alongside other early animators like Noburō Ōfuji and Kenzō Masaoka

- The film represents an early example of Japanese animators adapting traditional folk tales into animated form, a practice that would become common in later decades

- Underwater themes in early animation were relatively rare, making this film unusual for its time period

- The animation was likely created using the cut-out technique rather than full cel animation, which was more expensive and technically demanding

- Many early Japanese animated films from this period were lost due to natural disasters, war, and poor preservation conditions

- The film was created during the early sound era in Japan, though it was likely released as a silent film with musical accompaniment

- Momotaro stories were particularly popular in Japanese media during the 1930s as they emphasized traditional Japanese values and folklore

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of the film is difficult to ascertain due to limited documentation of film criticism for short animated works in 1930s Japan. However, films like this were generally well-received by audiences as novelty items during theatrical screenings. Modern film historians and animation scholars recognize the film as an important example of early Japanese animation, though it is often overshadowed by more well-known works from the period. The film is valued today for its historical significance and for demonstrating the early development of anime's distinctive visual style.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1932 Japan would have viewed this short film as part of a theatrical program, likely preceding a feature film. The combination of the familiar Momotaro story with the novelty of animation and the unusual underwater setting would have made it popular with viewers of all ages. Children particularly enjoyed animated shorts during this period, as they were a rare treat in cinema programming. The film's adherence to traditional Japanese values and folklore would have resonated strongly with contemporary audiences, especially during a period of increasing cultural nationalism.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Western animation techniques from Disney and Fleischer Studios

- Traditional Japanese ukiyo-e art style

- Japanese folk tales and mythology

- Silent era visual storytelling

This Film Influenced

- Later Momotaro adaptations in Japanese animation

- Early wartime propaganda animations

- Post-war Japanese animated films featuring folklore

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of this specific film is uncertain. Many early Japanese animated shorts from the 1930s have been lost due to poor storage conditions, wartime destruction, and the flammable nature of early film stock. Some prints may exist in private collections or film archives, but comprehensive restoration efforts for early Japanese animation are ongoing and challenging.