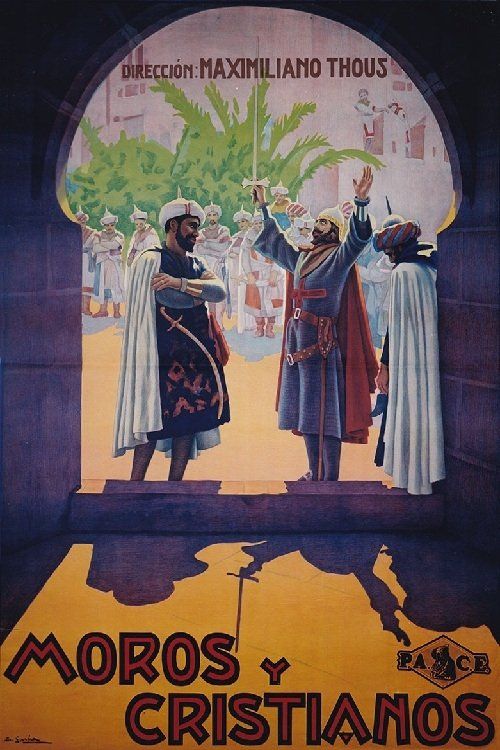

Moors and Christians

Plot

In this Spanish silent drama, Dolorcitas (played by Anita Giner), a young woman from a less aristocratic family, finds herself caught in a complex love triangle. Her husband Melchor Llorens (Leopoldo Pitarch), an ambitious entrepreneur, competes for her affection against Daniel Soler (Ramón Sernequet), a wealthy young man who squanders his family fortune. Daniel resorts to blackmail, attempting to tarnish Dolorcitas's reputation and drive a wedge between her and Melchor. The story culminates during the traditional Moros y Cristianos festival, where both men serve as captains, providing the dramatic backdrop for Daniel's exposure, the restoration of Dolorcitas's honor, and the reconciliation of her marriage.

About the Production

The film was notably shot on location during actual Moros y Cristianos festivals, capturing authentic cultural celebrations. Director Maximiliano Thous was known for his interest in documenting Spanish cultural traditions, and this film was part of his series of works exploring regional Spanish customs. The production faced challenges with the large-scale festival sequences, requiring coordination with actual festival organizers and hundreds of extras.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a pivotal period in Spanish history, specifically during the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923-1930). This era saw increased government support for Spanish cultural productions as part of a broader nationalist agenda. The film's focus on traditional Spanish festivals and customs aligned with the regime's emphasis on promoting Spanish identity and heritage. The 1920s also marked the golden age of silent cinema in Spain, with domestic productions competing with imported American and European films. The Moros y Cristianos festivals themselves have deep historical roots, dating back to the 16th century and commemorating the Reconquista - the centuries-long process by which Christian kingdoms reconquered the Iberian Peninsula from Muslim rule. By centering the narrative around this cultural tradition, the film tapped into deep-seated Spanish historical consciousness at a time when the country was grappling with questions of national identity.

Why This Film Matters

'Moors and Christians' represents an important milestone in Spanish cinema's engagement with national cultural traditions. The film is notable for its early attempt to blend fictional narrative with ethnographic documentation, capturing authentic Spanish folk traditions during a period of rapid modernization. It stands as a valuable visual record of 1920s Moros y Cristianos celebrations, which have continued to evolve over the decades. The film's approach of using traditional festivals as dramatic settings influenced subsequent Spanish filmmakers interested in exploring regional identities and customs. It also reflects the broader European trend of the 1920s where national cinemas sought to differentiate themselves from Hollywood productions by emphasizing local culture and traditions. The film's preservation and study by film historians and cultural anthropologists underscores its dual significance as both entertainment and cultural document.

Making Of

The production of 'Moors and Christians' was a significant undertaking for 1926 Spanish cinema. Director Maximiliano Thous, known for his ethnographic interest in Spanish culture, insisted on filming during actual Moros y Cristianos celebrations in Valencia and Alcoy. This required extensive coordination with local festival organizers and the participation of hundreds of actual festival attendees. The cast, primarily drawn from Valencia's theatrical community, had to integrate seamlessly with the real festival participants. The film's production coincided with a period of growing Spanish national cinema identity, and Thous's approach of blending fictional narrative with documentary elements was innovative for its time. The elaborate costumes and parade sequences presented significant technical challenges for the cinematography team, who had to capture the scale and spectacle of the festivals while maintaining narrative continuity.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Moors and Christians' was particularly notable for its treatment of large-scale outdoor scenes and festival sequences. The cinematographer employed long shots to capture the grandeur of the Moros y Cristianos parades, utilizing the natural architecture of Spanish towns as dramatic backdrops. The film made effective use of the panchromatic film stock that was becoming available in the mid-1920s, which allowed for better tonal differentiation in the elaborate and colorful festival costumes. The camera work during the festival scenes showed remarkable mobility for the period, with some tracking shots that followed parade processions through narrow streets. The contrast between the intimate domestic scenes and the expansive public festival sequences created a visual rhythm that reinforced the film's thematic concerns with private honor and public spectacle.

Innovations

The film demonstrated several technical achievements for Spanish cinema of its period. The successful integration of documentary footage of actual festivals with staged dramatic sequences was innovative for its time. The production team developed specialized camera mounts to capture the dynamic movement of festival parades, allowing for more fluid tracking shots than were typical in Spanish cinema of the era. The film also employed early forms of location sound recording to capture ambient festival noises, although these were not synchronized with the final release. The coordination required to film during actual festival events, involving hundreds of non-actors and real-time ceremonial activities, represented a significant logistical achievement. The film's use of natural lighting in outdoor scenes, particularly the golden hour lighting during sunset festival sequences, showed sophisticated understanding of cinematographic possibilities.

Music

As a silent film, 'Moors and Christians' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The original score likely incorporated traditional Spanish folk melodies and festival music, particularly arrangements of pieces typically performed during Moros y Cristianos celebrations. Theaters showing the film would have employed small orchestras or organists who adapted their performance to match the on-screen action, especially during the dramatic festival sequences. Some contemporary accounts mention that certain Valencia theaters used regional musicians familiar with the specific musical traditions depicted in the film, adding to the authenticity of the presentation. The musical accompaniment would have been particularly important during the extended festival scenes, helping to maintain audience engagement through the purely visual spectacle.

Famous Quotes

The honor of a woman is like the flag of our people - it must never be allowed to fall.

In the dance of Moors and Christians, we see the story of Spain itself - conflict, celebration, and ultimately, unity.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic festival sequence where both suitors lead their respective troops in the Moros y Cristianos parade, with the entire town serving as witness to the dramatic confrontation and resolution.

- The intimate domestic scene where Dolorcitas receives the blackmail letter, intercut with shots of the festival preparations, creating tension between private crisis and public celebration.

Did You Know?

- Director Maximiliano Thous was a pioneer of Spanish cinema who made over 30 films between 1914 and 1930

- The Moros y Cristianos festival depicted in the film is a real traditional celebration in Spanish communities, commemorating the battles between Moors and Christians during the Reconquista

- This film is considered one of the earliest examples of Spanish cinema incorporating traditional cultural festivals as central plot elements

- The film was shot using the then-new panchromatic film stock, which allowed for better tonal reproduction in the elaborate festival costumes

- Maximiliano Thous was not only a director but also a screenwriter and producer, often wearing multiple hats on his productions

- The film's original Spanish title was 'Moros y cristianos,' directly referencing the festival that serves as the story's climax

- Many of the festival scenes were filmed during actual celebrations, making it a valuable documentary record of 1920s Spanish folk traditions

- The film was distributed internationally under different titles, including 'Moors and Christians' in English-speaking markets

What Critics Said

Contemporary Spanish critics praised the film for its authentic representation of the Moros y Cristianas festival and its technical achievements in capturing large-scale public celebrations. The newspaper 'La Correspondencia de España' noted the film's 'magnificent spectacle' and praised Thous's ability to weave dramatic narrative into the fabric of real cultural events. Critics particularly commended the cinematography of the festival sequences, which they described as 'vivid and transporting.' However, some reviewers of the time found the romantic plot somewhat conventional compared to the innovative documentary elements. Modern film historians have reassessed the work as an important example of early Spanish ethnographic cinema, though they note that the film's dramatic elements occasionally take precedence over documentary authenticity. The film is now studied more for its cultural documentation value than its narrative innovations.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well received by Spanish audiences upon its release, particularly in Valencia and other regions where Moros y Cristianos festivals are traditionally celebrated. Local audiences appreciated seeing their cultural traditions represented on screen, and the film's release during the Christmas season of 1926 helped ensure strong attendance. The spectacle of the festival sequences drew audiences who might not typically attend dramatic films, expanding the film's reach beyond regular cinema-goers. However, the film's distribution was primarily limited to Spain, with limited international release, which constrained its broader audience impact. Contemporary audience accounts suggest that viewers were particularly moved by the authentic festival footage, with many recognizing familiar faces and locations from their own communities.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German expressionist cinema

- Italian historical epics

- Spanish literary traditions

- Ethnographic documentary

- Contemporary Spanish melodrama

This Film Influenced

- La aldea maldita (1930)

- El verdugo (1963)

- La fiesta (1977)

- Los santos inocentes (1984)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with some missing sequences. Several reels are held in the Filmoteca de Catalunya in Barcelona, while additional fragments exist in the Filmoteca Española in Madrid. Some of the festival sequences have been restored and are occasionally screened at film festivals specializing in Spanish cinema. The film's incomplete status reflects the challenges of preserving Spanish silent films from the 1920s, many of which were lost or damaged during the Spanish Civil War and subsequent periods.