Once More

"Love that survived the storm of war"

Plot

Once More tells the poignant story of Masako, a sheltered bourgeois woman, and Dr. Takagi, a dedicated physician who devotes his life to caring for the poor in rural Japan. Their paths first cross in 1936 when Masako's father brings her to Takagi's clinic for treatment, sparking an immediate connection between the privileged young woman and the idealistic doctor. Over the next decade, their relationship develops amidst growing political tensions and the approaching war, with Takagi's socialist leanings and commitment to the underprivileged clashing with Masako's upper-class background. The outbreak of World War II forces their separation, as Takagi is called to serve as a military doctor while Masako remains in Tokyo, facing the hardships of war on the home front. Through letters and brief reunions, their love endures despite the chaos and destruction surrounding them, culminating in a post-war reunion where they must decide if their love can survive in Japan's new reality.

About the Production

Filmed during the challenging immediate post-war period when Japan faced severe shortages of film stock and equipment. Director Gosho had to work with limited resources, often using natural lighting and available locations. The production was one of the first Japanese films to directly address the war years and their impact on ordinary people, making it somewhat controversial with the Allied occupation authorities who initially had concerns about its political content.

Historical Background

Once More was produced during a pivotal moment in Japanese history - the immediate aftermath of World War II and the beginning of the American occupation. The film was made in 1947, when Japan was undergoing massive social, political, and economic transformation under Allied supervision. The occupation authorities were actively promoting democratic values and questioning pre-war social hierarchies, making Gosho's focus on class differences and social responsibility particularly relevant. The film's examination of the war years from the perspective of ordinary Japanese citizens was groundbreaking, as most previous Japanese films had either avoided direct reference to the war or presented it from a nationalistic perspective. The production coincided with the drafting of Japan's new constitution and the beginning of the country's economic recovery, themes that resonate throughout the film's narrative of rebuilding and renewal.

Why This Film Matters

Once More holds an important place in Japanese cinema history as one of the first films to honestly confront Japan's recent wartime past while looking toward a democratic future. The film's portrayal of a romance that transcends class barriers reflected the occupation's emphasis on social equality and democratic values. Director Gosho's humanistic approach and focus on ordinary people's struggles established a template for post-war Japanese cinema that would influence directors like Akira Kurosawa and Yasujirō Ozu. The film's success helped establish Shochiku as a leading studio for serious dramatic films in the post-war era and demonstrated that Japanese audiences were ready for more realistic, socially conscious storytelling. Its depiction of medical professionals serving the poor also contributed to a broader cultural discussion about social responsibility in Japan's new democratic society.

Making Of

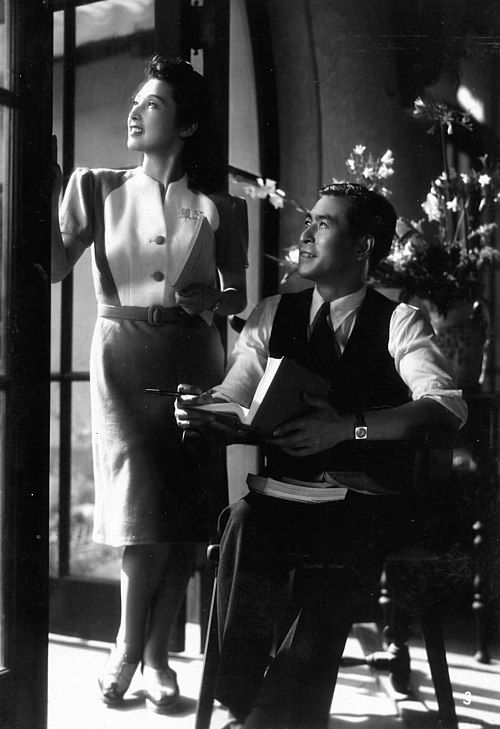

The production of Once More faced numerous challenges typical of the immediate post-war Japanese film industry. Director Heinosuke Gosho, who had been evacuated from Tokyo during the war, drew heavily from his personal experiences witnessing the struggles of rural communities and medical professionals during the conflict. The casting of Mieko Takamine as Masako was particularly significant, as she was one of the few major stars who had not been blacklisted for appearing in wartime propaganda films. The relationship between Takamine and Ryūzaki was so convincing on screen that rumors of a real-life romance circulated, though both actors maintained they were just professional colleagues. The film's most challenging sequences involved recreating the Tokyo air raids, which required careful coordination with occupation authorities and the use of actual damaged city locations.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Masao Tamai is notable for its blend of classical Japanese composition with emerging neorealist influences. Tamai employed natural lighting techniques for the rural clinic scenes, creating a sense of authenticity that contrasted with the more stylized lighting used for the bourgeois sequences. The film's visual language subtly reinforces its themes of class division, with the wealthy characters' scenes featuring soft, romantic lighting while the poor communities are shown in harsher, more realistic illumination. The war sequences utilize handheld camera work and documentary-style framing techniques that were innovative for Japanese cinema at the time. Tamai's use of deep focus in several key scenes allows for complex visual storytelling, particularly in scenes showing the contrast between wealth and poverty.

Innovations

Once More pioneered several technical innovations in post-war Japanese cinema. The film was among the first to use location shooting in actual war-damaged areas of Tokyo, requiring portable equipment and creative solutions to power shortages. The production team developed new techniques for simulating air raid effects using limited resources, creating sequences that were both realistic and safe. The film's editing, particularly in the montage sequences showing the passage of time, influenced subsequent Japanese filmmakers dealing with historical narratives. The sound recording team overcame significant challenges in capturing clear dialogue in locations with damaged infrastructure, developing new microphone placement techniques that would become standard practice in the industry.

Music

The musical score was composed by Yasushi Shimamura, who created a soundtrack that blended Western classical influences with traditional Japanese elements. The main love theme, performed on violin and koto, became one of the most recognized musical pieces in Japanese cinema of the era. Shimamura's use of silence in several key scenes was particularly innovative, allowing the emotional weight of moments to carry without musical accompaniment. The soundtrack also incorporates period-appropriate songs that help establish the historical setting, including military marches and popular songs from the late 1930s and early 1940s. The film's sound design was praised for its realism, particularly in the sequences depicting air raids and their aftermath.

Did You Know?

- The film was one of the first major Japanese productions to receive approval from the Civil Censorship Detachment (CCD) of the Allied occupation forces, which was reviewing all Japanese media content.

- Mieko Takamine and Ichirō Ryūzaki would go on to star together in several more films, becoming one of Japan's most beloved screen couples of the late 1940s.

- Director Heinosuke Gosho was reportedly inspired to make this film after witnessing the struggles of doctors in rural communities during his evacuation from Tokyo during the war.

- The film's title 'Once More' refers to both the lovers' repeated separations and reunions, as well as Japan's need to rebuild society 'once more' after the devastation of war.

- Many of the exterior scenes showing war-torn Tokyo were filmed on location in actual damaged areas, giving the film an unprecedented documentary-like realism.

- The original script was significantly longer, but had to be cut due to film stock shortages in post-war Japan.

- The film's release coincided with the Japanese Constitution being promulgated, adding to its themes of social reconstruction.

- Gosho used non-professional actors for some of the rural clinic scenes to enhance authenticity.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Once More for its courageous approach to recent Japanese history and its sensitive handling of difficult subject matter. The Kinema Junpo film journal specifically highlighted the film's 'brave honesty' and 'profound humanism' when naming it the best film of 1947. Western critics, when the film was eventually shown abroad in the early 1950s, were impressed by its technical sophistication and emotional depth, with Variety noting that it 'transcends national boundaries in its universal themes of love and social responsibility.' Modern film historians regard Once More as a crucial transitional work in Japanese cinema, marking the shift from wartime propaganda to the golden age of Japanese film that would emerge in the 1950s. The film is particularly noted for how it balances personal drama with broader social commentary without becoming didactic.

What Audiences Thought

Once More was a commercial success upon its release in Japan, resonating strongly with audiences who had lived through the war years and were experiencing similar challenges in their own lives. The film's themes of separation, reunion, and rebuilding struck a chord with a population dealing with loss and displacement. Mieko Takamine's performance as Masako was particularly beloved, with many female viewers seeing in her character a reflection of their own struggles and hopes for the future. The film's realistic depiction of war-torn Tokyo and rural Japan also drew praise from audiences who appreciated its authenticity. Box office records indicate it was one of the highest-grossing Japanese films of 1947, though exact figures are not available due to the chaotic state of the Japanese film industry at the time.

Awards & Recognition

- Kinema Junpo Award for Best Film of 1947

- Mainichi Film Award for Best Director (Heinosuke Gosho)

- Mainichi Film Award for Best Actress (Mieko Takamine)

- Mainichi Film Award for Best Screenplay

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Italian neorealism

- Japanese pre-war humanist cinema

- Hollywood romantic dramas of the 1930s

- German expressionist lighting techniques

- Traditional Japanese literary romances

This Film Influenced

- Late Spring

- 1949

- by Yasujirō Ozu),

- The Bad Sleep Well

- 1960

- by Akira Kurosawa),

- The Human Condition

- trilogy (1959-1961 by Masaki Kobayashi),

- The Family Game

- 1983

- by Yoshishige Yoshida)],

- similarFilms

- A Ball at the Anjo House,1947,Green Mountains,1949,The Life of Oharu,1952,Ugetsu,1953,The River,1956,The Human Condition,1959,],,famousQuotes,In times like these, caring for one person is the same as caring for the whole world.,Love doesn't care about class or position - it only cares about hearts.,We may be separated by war, but our hearts remain together.,A doctor's duty is not just to heal bodies, but to heal society's wounds.,Even in the darkest times, we must hold on to the hope of meeting once more.,memorableScenes,The opening scene where Masako first visits Dr. Takagi's rural clinic, showing the stark contrast between her privileged world and the poverty of the patients.,The sequence depicting the Tokyo air raids, using actual damaged locations and innovative special effects to convey the horror of civilian suffering.,The emotional reunion scene in the ruined Tokyo train station where the lovers meet after years of separation.,The final scene where Dr. Takagi returns to his clinic to find it rebuilt with community support, symbolizing Japan's post-war recovery.,preservationStatus,The original negatives of Once More were believed lost for decades but were discovered in the Shochiku archives in the 1980s. The film underwent a major restoration by the National Film Center of Japan in 1995, with funding from the Martin Scorsese Film Foundation and the World Cinema Project. A 4K restoration was completed in 2018 as part of a comprehensive Shochiku classic film preservation initiative. The restored version has been screened at major film festivals including Cannes and Venice, bringing this important work to new international audiences.,whereToWatch,The Criterion Channel (streaming),Janus Films DVD/Blu-ray collection,Mubi (occasional streaming),Film Movement DVD collection,Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) film screenings,Japanese Film Archive screenings,Kanopy (educational streaming),BFI Player (UK streaming)