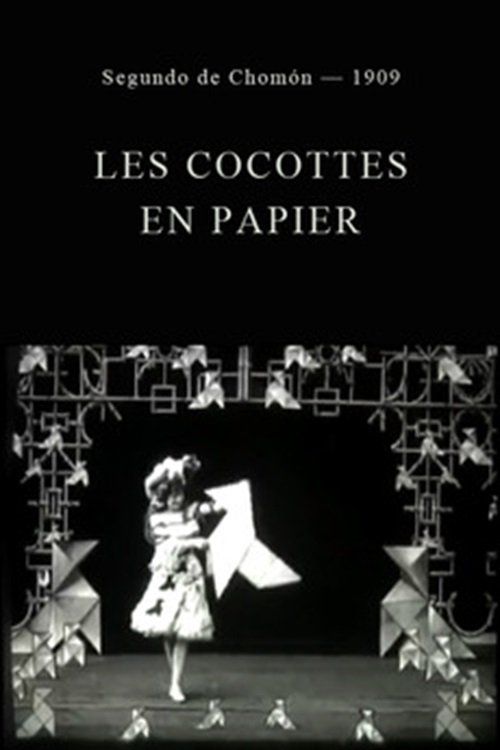

Paper Cock-a-Doodles

Plot

In this whimsical trick film, two female magicians perform an extraordinary stage show where they demonstrate their supernatural powers of transformation. The magicians select members from the audience and, through magical gestures and special effects, transform them into elaborate paper roosters that come to life. These origami creatures then perform animated dances and movements on stage before the magicians reverse the spell, returning them to human form. The film showcases a series of metamorphosis effects that highlight the magicians' control over both paper and living matter, culminating in a grand finale where multiple transformations occur simultaneously.

Director

Cast

About the Production

The film utilized multiple exposure techniques and stop-motion animation to create the paper transformation effects. De Chomón employed his innovative hand-coloring process where each frame was manually tinted to enhance the magical atmosphere. The paper roosters were likely created using actual origami models animated through frame-by-frame photography, a technique that was groundbreaking for its time.

Historical Background

1908 was a pivotal year in cinema history, marking the transition from simple actualities and trick films to more sophisticated narrative storytelling. The film industry was rapidly expanding globally, with Pathé Frères dominating the international market. During this period, audiences were fascinated by films that showcased seemingly impossible transformations and magical effects, reflecting the era's interest in spiritualism, stage magic, and technological progress. The film emerged during the golden age of trick films, when directors like Georges Méliès and Segundo de Chomón were pushing the boundaries of what was possible with the new medium of cinema.

Why This Film Matters

'Paper Cock-a-Doodles' represents an important milestone in the development of animation and special effects in cinema. The film's innovative use of stop-motion techniques with paper models prefigured later developments in puppet animation and contributed to the evolution of animated filmmaking. It also demonstrates how early cinema borrowed from traditional arts like origami and stage magic to create new forms of entertainment. The film's success helped establish the template for magical transformation films that would remain popular throughout the silent era. Its preservation of early special effects techniques provides valuable insight into the technical capabilities and artistic ambitions of pioneering filmmakers.

Making Of

The production of 'Paper Cock-a-Doodles' represented the pinnacle of early special effects filmmaking. De Chomón and his team spent considerable time perfecting the paper transformation sequences, which involved creating multiple origami roosters of varying sizes and photographing them frame by frame. The studio environment was carefully controlled to ensure consistent lighting for the multiple exposure shots. Julienne Mathieu had to perform her magical gestures with precise timing to match the special effects that would be added later in post-production. The hand-coloring process was particularly labor-intensive, with teams of artists working for weeks to paint each frame by hand, creating the vibrant colors that made the magical effects more convincing to audiences.

Visual Style

The cinematography employed multiple innovative techniques for its time, including multiple exposure, substitution splicing, and stop-motion animation. The camera work was carefully choreographed to create smooth transitions between live action and animated sequences. De Chomón utilized a stationary camera setup typical of the era, but achieved dynamic visual effects through in-camera techniques and post-production manipulation. The lighting was carefully controlled to facilitate the special effects, with bright, even illumination necessary for the multiple exposure shots that created the transformation effects.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in early cinema, particularly in the realm of special effects and animation. De Chomón's sophisticated use of multiple exposure allowed for seamless transformation effects that were more advanced than many contemporary films. The stop-motion animation of paper models represented an early form of object animation that would later influence the development of puppet animation. The film also showcased advanced hand-coloring techniques, with each frame individually painted to create vibrant colors that enhanced the magical atmosphere. These technical achievements demonstrated the growing sophistication of cinematic effects in the early 20th century.

Music

As a silent film from 1908, 'Paper Cock-a-Doodles' had no synchronized soundtrack. During theatrical screenings, the film would have been accompanied by live musical performance, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing appropriate mood music. The musical accompaniment would have been improvisational or based on cue sheets provided by Pathé, suggesting appropriate musical themes for magical moments, transformations, and the film's whimsical atmosphere.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue - silent film

Memorable Scenes

- The central transformation sequence where audience members are magically converted into animated paper roosters, showcasing de Chomón's mastery of multiple exposure and stop-motion techniques in a seamless flow of metamorphosis that amazed 1908 audiences

Did You Know?

- The film is also known by its French title 'Les Coqs en Papier' and Spanish title 'Los Gallos de Papel'

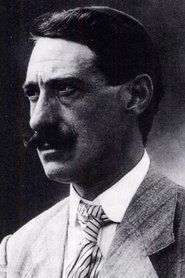

- Julienne Mathieu, who plays one of the magicians, was Segundo de Chomón's wife and frequent collaborator in his films

- The paper rooster effects were created using a combination of stop-motion animation and substitution splicing techniques

- This film was part of Pathé's popular 'magical transformation' series that capitalized on audiences' fascination with trick films

- De Chomón was often called 'the Spanish Méliès' due to his similar style of fantasy and special effects films

- The hand-coloring process used in this film could take weeks to complete, with artists painting each individual frame

- Paper folding and origami were relatively unknown in Western Europe at the time, making the subject matter particularly exotic

- The film was distributed internationally and shown in both European and American theaters

- De Chomón's innovative use of multiple exposure in this film influenced later animators and special effects artists

- The transformation sequences required precise timing and coordination between the actors and the camera operators

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its clever special effects and the seamless nature of the transformations. Trade publications of the era, such as 'The Bioscope' and 'Moving Picture World', noted the film's technical sophistication and its appeal to family audiences. Critics particularly highlighted the originality of using paper origami as the central theme, which distinguished it from other transformation films of the period. Modern film historians recognize the work as an exemplary piece of early cinema that showcases de Chomón's mastery of special effects and his contribution to the development of animation techniques.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by audiences of 1908, who were consistently amazed by the seemingly magical transformations on screen. Theater owners reported strong attendance for screenings, particularly in family-oriented venues. The visual spectacle of paper roosters coming to life captivated viewers and contributed to the film's popularity in both European and American markets. The film's short runtime and clear visual narrative made it accessible to international audiences, helping it achieve commercial success across multiple countries.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès' trick films

- Stage magic performances

- Japanese origami art

- Traditional European folklore about transformation

This Film Influenced

- Early stop-motion animation films of the 1910s

- Later Pathé magical films

- Object animation pioneers like Ladislas Starevich

- Fantasy animation of the 1920s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in archives and is considered preserved. Prints are held by major film archives including the Cinémathèque Française and the Library of Congress. Some versions retain the original hand-coloring, though many surviving copies are black and white. The film has been digitally restored for inclusion in early cinema collections and DVD compilations of Segundo de Chomón's work.