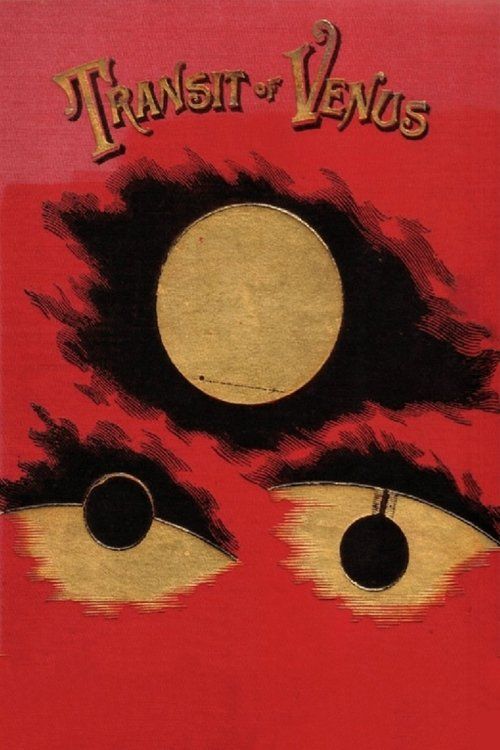

Passage of Venus

Plot

Passage of Venus is a groundbreaking scientific film that documents the rare transit of Venus across the face of the Sun using Pierre Jules César Janssen's revolutionary Photographic Revolver. The sequence consists of a series of photographs captured automatically at regular intervals, showing Venus as a small dark disk moving across the bright solar surface in a curved path. Created as part of an international scientific effort to observe and measure the 1874 transit, this work represents one of the earliest examples of sequential photography that would evolve into motion pictures. The film was designed to provide permanent visual evidence of this astronomical phenomenon for scientific study and to help calculate the astronomical unit. This brief but historically significant sequence captures a celestial event that occurs only in pairs separated by eight years, with over a century between each pair.

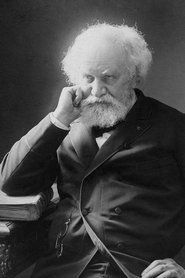

Director

About the Production

This film was created as part of a massive international scientific effort to observe the December 9, 1874 transit of Venus. Janssen developed his Photographic Revolver specifically for this expedition, which required traveling to Japan to obtain optimal viewing conditions. The device could capture 48 images in 72 seconds using a Maltese cross mechanism. The production faced numerous technical challenges including the primitive state of photography, difficult travel conditions to remote observation sites, and the need to synchronize multiple international observations. The photographic plates had to be prepared and developed on-site under field conditions, making this an extremely ambitious undertaking for 1874.

Historical Background

The year 1874 was a period of intense scientific advancement and international cooperation during the height of the Victorian era. The Second French Empire under Napoleon III was promoting scientific research as part of France's effort to regain prestige after the Franco-Prussian War. The transit of Venus was one of the most significant astronomical events of the 19th century, as it offered a rare opportunity to measure the astronomical unit - the distance from Earth to the Sun. International scientific collaboration was relatively new, and the 1874 transit observations represented one of the first truly global scientific endeavors. Photography itself was still in its infancy, having been invented only about 35 years earlier, and capturing moving images was considered impossible by most. This was also the year that Alexander Graham Bell began his work on the telephone, and Thomas Edison was establishing his invention laboratory. The world was on the cusp of the Second Industrial Revolution, with rapid technological advances transforming science and society. The transit observations represented the pinnacle of 19th-century scientific ambition, combining astronomy, photography, and international cooperation in a way that had never been attempted before.

Why This Film Matters

Passage of Venus represents a pivotal moment in the history of both cinema and science, marking one of the earliest examples of what would become motion picture technology. This work demonstrates how scientific necessity drove technological innovation that would later be adapted for entertainment and artistic purposes. The Photographic Revolver concept directly influenced subsequent pioneers like Étienne-Jules Marey, whose chronophotographic work in turn influenced the Lumière brothers and other early cinema developers. The film shows how early cinema emerged not from entertainment but from the human desire to document and understand the world. Scientifically, it represents one of the first systematic uses of photography to study astronomical phenomena, establishing methods that would be used throughout the 20th century. The work also exemplifies 19th-century faith in technology's ability to capture and preserve reality, a theme that would become central to cinema's cultural role. Today, it stands as a testament to the intersection of art and science, showing how the quest for knowledge can produce innovations that transcend their original purpose. The sequence is frequently cited in film history texts as a crucial precursor to modern cinema, representing the moment when still photography began to move.

Making Of

Pierre Jules César Janssen, a prominent French astronomer, conceived the Photographic Revolver out of necessity to capture the 1874 transit of Venus. The device was a remarkable feat of engineering for its time, combining astronomical observation with cutting-edge photography. Janssen traveled to Japan as part of the French expedition, joining scientists from Britain, America, Germany, and other nations who spread across the globe to observe the transit from different locations. The Photographic Revolver used a rotating disc with photographic plates that automatically advanced and exposed at precise intervals, creating what we now recognize as a motion picture sequence. The technical challenges were immense - the wet collodion photographic process required plates to be prepared immediately before exposure and developed quickly after, all while maintaining precise timing to capture the transit. Janssen's team worked under difficult field conditions in Nagasaki, dealing with humidity, temperature fluctuations, and the pressure of capturing a once-in-a-lifetime event. The device's automatic operation was crucial as it eliminated human error in timing, ensuring consistent intervals between exposures. This scientific necessity drove technological innovation that would ultimately contribute to the birth of cinema.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Passage of Venus consists of a series of still photographs captured sequentially using Janssen's Photographic Revolver attached to a telescope. Each frame shows Venus as a dark circular silhouette moving across the bright disk of the Sun, following a curved path due to the relative motions of Earth, Venus, and the Sun. The device used a special dark filter to protect the photographic plates from the Sun's intense brightness while still capturing the transit. The sequence was created automatically through a mechanical system that advanced photographic plates and exposed them at precise intervals, eliminating human error in timing. The resulting images show remarkable clarity for 1874 technology, with Venus clearly visible against the solar surface. The composition is simple yet effective - centered framing with the Sun filling most of each frame, creating a consistent visual field that makes Venus's movement immediately apparent. This early form of time-lapse photography compressed a six-hour astronomical event into a sequence that could be viewed in seconds, representing a revolutionary approach to visual documentation. The technical achievement of maintaining consistent framing and exposure across multiple automatic exposures was extraordinary for its time.

Innovations

The Photographic Revolver represented a groundbreaking technical achievement that combined multiple innovations in photography, mechanics, and astronomy. The device could capture 48 images in 72 seconds using a sophisticated Maltese cross mechanism that would later become standard in movie projectors. It featured a rotating disc with photographic plates that automatically advanced and exposed at precise intervals without human intervention. The mechanical precision required to maintain consistent timing between exposures was extraordinary for 1874 technology. The device also incorporated innovative light-filtering systems to allow photography of the Sun without overexposing the plates. The automatic operation was revolutionary, eliminating the human variable in sequential photography. The wet collodion photographic process used required plates to be prepared and developed immediately, making the entire system remarkable for its field operability. The device's ability to capture transient phenomena automatically made it a direct precursor to motion picture cameras. Janssen's invention influenced subsequent developments in chronophotography and ultimately contributed to the invention of cinema. The technical challenges overcome included precise mechanical timing, reliable automatic plate advancement, consistent exposure control, and field-portable operation - all remarkable achievements for 1874.

Music

No soundtrack existed for this 1874 film, as motion picture sound technology would not be developed for another 50+ years. The film was a silent scientific document created long before the concept of synchronized sound with moving images was conceived. When the sequence is shown today in museums or documentaries, it is typically accompanied by period-appropriate music or explanatory narration, but the original work was completely silent.

Famous Quotes

The photographic revolver is designed to capture a series of images automatically, without human intervention, to serve as evidence of celestial phenomena. - Pierre Jules César Janssen

We have succeeded in fixing upon a sensitive surface the image of Venus traversing the solar disc. - Janssen's report to the French Academy of Sciences

This apparatus may be applied to the study of all phenomena which succeed each other with sufficient rapidity. - Janssen on the broader applications of his invention

Memorable Scenes

- The entire sequence showing Venus as a dark disk moving in a curved path across the bright circular face of the Sun, creating one of the first motion picture sequences in history and capturing a rare astronomical event that occurs only twice per century

Did You Know?

- This is considered one of the first motion picture sequences ever created, predating Edison's Kinetoscope by nearly 20 years

- The Photographic Revolver was inspired by the revolving cylinder mechanism of a gun, hence its name

- Janssen's device used a Maltese cross mechanism, later adopted in movie projectors

- The transit of Venus occurs in pairs separated by 8 years, with over 100 years between pairs - the next after 1874 was in 1882

- The 1874 transit was the first in history to be successfully photographed

- Janssen's invention directly influenced Étienne-Jules Marey's chronophotography work

- The sequence was created to help scientists measure the astronomical unit (Earth-Sun distance)

- This film was created before the concept of 'cinema' or 'movies' even existed

- Janssen presented his device to the French Academy of Sciences in 1873, a year before the transit

- The photographic process used wet collodion plates, which had to be prepared immediately before exposure

- Multiple international expeditions were sent around the world to observe the 1874 transit from different locations

- The original plates are preserved in French scientific archives and are extremely fragile

- This work bridges the gap between still photography and motion pictures

- The sequence captures a phenomenon that lasts over 6 hours in real-time, compressed into seconds

- Janssen's method was so innovative that it was initially met with skepticism by some contemporaries

What Critics Said

As a scientific document from 1874, Passage of Venus did not receive critical reception in the modern sense, as the concept of film criticism did not yet exist. However, the scientific community recognized the significance of Janssen's innovation. The French Academy of Sciences officially acknowledged the Photographic Revolver as an important advancement in astronomical photography. Contemporary scientific journals, including Comptes Rendus and Nature, published detailed accounts of Janssen's method, praising its potential for capturing transient phenomena. Astronomers from other countries expressed admiration for the technical ingenuity of the device, though some initially questioned its practicality. Modern film historians and critics universally recognize this work as a foundational moment in cinema history. It is regularly featured in documentaries about the origins of motion pictures and cited in academic works on early cinema. Contemporary critics often highlight how this scientific work inadvertently created one of the first motion picture sequences, demonstrating how technological innovation often precedes its cultural applications.

What Audiences Thought

Passage of Venus was not intended for public exhibition or entertainment audiences, so there was no contemporary audience reception in the traditional sense. The primary 'audience' consisted of astronomers and scientists who used the photographic plates for calculations and research. These scientific viewers appreciated the technical achievement and the utility of the images for their work. The general public would not have seen these images until decades later when they were recognized for their historical importance in the development of cinema. When the sequence was later rediscovered by film historians, it generated excitement among cinema enthusiasts and scholars who recognized its significance. Modern audiences viewing the sequence today are often struck by its simplicity and historical importance, seeing in these few frames the origins of an entire art form. The work now appears in film museums, cinema history courses, and documentaries about early photography, where it is appreciated both for its scientific merit and its role in cinema history.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Early astronomical photography

- Wet collodion photographic process

- Scientific illustration traditions

- 19th century astronomical observation methods

- International scientific collaboration models

- Precision measurement techniques

- Mechanical automation developments

This Film Influenced

- Étienne-Jules Marey's chronophotographic studies

- Eadweard Muybridge's motion sequences

- Lumière brothers' early films

- Georges Méliès's astronomical films

- Early scientific documentaries

- Time-lapse photography works

- Modern astronomical photography

- Space documentary films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original photographic plates from Janssen's 1874 expedition are preserved in the archives of the French Academy of Sciences and the Paris Observatory. These historical artifacts are extremely fragile due to their age and the 19th-century wet collodion photographic process used. The sequence has been carefully digitized by film historians and scientific institutions for preservation and study purposes. High-quality digital copies exist in several film archives and museum collections. The original plates are stored in climate-controlled conditions and are handled only for conservation purposes. Some reproductions have been made using modern photographic techniques to create stable copies for exhibition and study. The work is considered historically significant enough to warrant ongoing conservation efforts, though the original materials will inevitably continue to deteriorate despite best preservation practices.