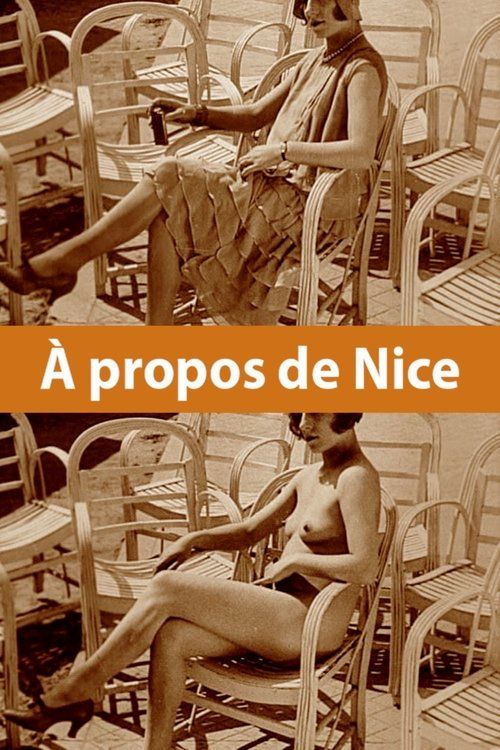

À propos de Nice

"Un voyage qui n'est pas un voyage, une critique qui n'est pas une critique"

Plot

Jean Vigo's groundbreaking film begins as a conventional travelogue showcasing the picturesque French Riviera resort town of Nice, but quickly transforms into a biting social satire. The film juxtaposes images of wealthy tourists lounging on beaches and gambling at casinos with stark footage of the working-class residents who maintain the city's infrastructure. Through innovative editing techniques and surrealist imagery, Vigo exposes the artificiality and emptiness behind the glamorous facade of the Côte d'Azur. The documentary employs rapid cuts, superimpositions, and unconventional camera angles to create a powerful critique of class inequality and the commodification of leisure. The film culminates in a carnival sequence that serves as a metaphor for the chaotic, performative nature of society itself.

Director

About the Production

Filmed over several weeks in early 1930 using a handheld camera, which was revolutionary for documentary filmmaking. Vigo and cinematographer Boris Kaufman often hid their cameras to capture authentic footage of unsuspecting subjects. The film was shot on location without permits, sometimes requiring the crew to flee from authorities. The production was financed by Vigo's father-in-law, allowing him creative freedom from commercial constraints.

Historical Background

À propos de Nice was created during a pivotal period in French cinema between the World Wars, when avant-garde movements were challenging traditional filmmaking. The late 1920s and early 1930s saw the rise of Surrealism in France, with artists and filmmakers experimenting with new forms of expression. The film emerged during the Great Depression's early stages, when class tensions were rising across Europe. Nice, as a playground for the international wealthy elite, represented the stark inequalities of the era. The documentary form itself was evolving from purely observational to more subjective and critical approaches. This period also saw technological advances in portable camera equipment, enabling filmmakers like Vigo to capture more spontaneous and authentic footage. The film's creation coincided with the transition from silent to sound cinema, making it part of the last wave of significant silent documentaries.

Why This Film Matters

À propos de Nice revolutionized documentary filmmaking by introducing subjectivity and social critique into what had been a predominantly observational genre. The film's innovative editing techniques and satirical approach influenced countless filmmakers, particularly the French New Wave directors of the 1950s and 1960s who cited Vigo as a major inspiration. It established the concept of the 'essay film,' blending documentary footage with artistic expression and social commentary. The movie's critical view of tourism and consumer culture remains remarkably relevant today, presaging modern critiques of the hospitality industry and wealth inequality. Its preservation and restoration have made it a cornerstone of film studies programs worldwide, where it's studied as a prime example of avant-garde cinema and political filmmaking. The film's influence extends beyond cinema to photography, art, and social documentary work, where its techniques continue to inspire artists seeking to blend aesthetics with social consciousness.

Making Of

Jean Vigo, working with cinematographer Boris Kaufman, employed guerrilla filmmaking techniques to capture authentic footage of Nice society. The two would often disguise themselves as tourists to avoid detection while filming the wealthy residents. Kaufman developed innovative camera techniques, including mounting cameras on moving objects to create dynamic shots. The editing process took months, with Vigo experimenting with rapid cuts and superimpositions to create the film's satirical tone. The production faced numerous challenges, including lack of funding, weather delays, and occasional harassment from local authorities who were suspicious of their activities. Despite these obstacles, Vigo's determination and artistic vision resulted in a groundbreaking work that would influence generations of filmmakers.

Visual Style

Boris Kaufman's cinematography in À propos de Nice was revolutionary for its time, employing techniques that would later become standard in documentary filmmaking. He used handheld cameras to capture spontaneous, unscripted moments, creating a sense of immediacy and authenticity that was unprecedented. Kaufman experimented with unusual camera angles, including low-angle shots to emphasize the grandeur of architecture and high-angle shots to create a sense of detachment from human subjects. The film features innovative tracking shots, where cameras were mounted on moving objects to create fluid motion. Kaufman also utilized rapid camera movements and focus shifts to create a sense of visual energy and chaos during the carnival sequences. The black and white photography demonstrates exceptional contrast and composition, with Kaufman using light and shadow to emphasize the film's social commentary. His work on this film would later influence his Oscar-winning cinematography in Hollywood films like 'On the Waterfront.'

Innovations

À propos de Nice pioneered numerous technical innovations that would influence documentary filmmaking for decades. The film was among the first to use handheld cameras extensively for documentary work, allowing for unprecedented mobility and spontaneity. Vigo and Kaufman developed special camera mounts and rigs that enabled shots previously impossible in documentary filming. The film's editing was groundbreaking, featuring rapid cuts, jump cuts, and superimpositions that created a rhythmic, almost musical quality. It was one of the first documentaries to employ montage theory for social commentary rather than just narrative purposes. The film also experimented with time-lapse photography and slow-motion effects to create surreal visual metaphors. Its use of focus shifts and rack focusing techniques was highly innovative for the time. The production overcame technical limitations of early film equipment through creative solutions, including adapting existing cameras for handheld use and developing new film processing techniques to achieve desired visual effects.

Music

As a silent film, À propos de Nice was originally accompanied by live musical performances during its theatrical run. The original score was composed by Vigo himself, who worked with musicians to create a soundtrack that complemented the film's satirical tone and rapid editing. The music incorporated popular French songs of the era, classical pieces, and original compositions, often using ironic juxtapositions to enhance the film's critical perspective. For the carnival sequence, Vigo selected upbeat, chaotic music to mirror the visual chaos on screen. Modern restorations of the film have featured newly commissioned scores by contemporary composers, each offering different interpretations of Vigo's vision. Some versions use period-appropriate French music from the 1920s and 1930s, while others employ modern experimental compositions. The film's rhythmic editing creates a musical quality in its visual structure, making the relationship between image and sound particularly important to its overall impact.

Famous Quotes

The camera is a weapon against the hypocrisy of our time.

I wanted to make a film that would be a mirror held up to society, but a distorted mirror that shows the truth.

Tourism is the modern form of colonialism - we invade, we consume, we leave nothing but footprints in the sand.

The wealthy don't live in Nice, they only perform their wealth there.

A carnival is the only time when the masks come off and everyone can see what they really are.

I filmed Nice not as it is, but as it feels to those who serve it.

The sea doesn't care about wealth or poverty - it washes over everyone equally.

Every frame of this film is a lie that tells the truth.

The camera doesn't lie, but the person holding it can choose what truth to show.

In Nice, even the poverty looks picturesque from a distance.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where the camera pans across the luxurious hotels and casinos, immediately establishing the film's critical tone through ironic juxtapositions of wealth and service workers

- The famous carnival sequence where masked dancers and chaotic celebrations serve as a metaphor for the performative nature of society

- The beach scene contrasting sunbathing wealthy tourists with fishermen working in the background, highlighting class disparities

- The casino sequence where rapid cuts between gamblers' faces and spinning roulette wheels create a dizzying critique of excess

- The market scene where the camera focuses on the hands of workers preparing food for the wealthy tourists

- The closing sequence of garbage collectors cleaning up after the wealthy tourists have departed, serving as a powerful metaphor for social inequality

Did You Know?

- This was Jean Vigo's directorial debut at age 25, and he died just four years later at age 29 from tuberculosis

- Cinematographer Boris Kaufman was the brother of famous Soviet filmmakers Dziga Vertov and Mikhail Kaufman

- The film was initially banned by French authorities for its critical view of the wealthy establishment

- Vigo and his wife Lydou sold their personal belongings to help finance the production

- The carnival sequence was filmed during an actual Nice carnival, capturing spontaneous, unscripted moments

- The film's title translates to 'About Nice' but carries the dual meaning of being 'on the subject of' and 'concerning'

- Only one original print survived, which was later restored by the Cinémathèque Française

- The film influenced the French New Wave directors of the 1950s and 1960s

- Vigo used a special camera mount that allowed for unusual angles and movements

- The film's editing style was influenced by Soviet montage theory and surrealist art

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release, À propos de Nice received mixed reactions from critics, many of whom were unprepared for its radical approach to documentary filmmaking. Some mainstream critics dismissed it as amateurish and overly experimental, while avant-garde publications praised its bold vision and technical innovation. Over time, critical opinion has shifted dramatically in the film's favor, with modern critics hailing it as a masterpiece of early cinema. François Truffaut called it 'one of the most beautiful films ever made,' while Jean-Luc Godard cited it as a major influence on his work. Contemporary critics appreciate its prescient social commentary and groundbreaking techniques, with many considering it ahead of its time in both style and substance. The film now regularly appears in critics' lists of the greatest documentaries ever made and is studied as a landmark in the evolution of non-fiction cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception to À propos de Nice was limited due to its avant-garde nature and brief theatrical run. Those who did see it were often confused or shocked by its unconventional structure and critical tone. The film found its primary audience among artistic and intellectual circles in Paris, where it was appreciated for its experimental approach. Over the decades, as Vigo's reputation grew and the film became more accessible through screenings at cinematheques and film festivals, audience appreciation increased significantly. Modern audiences, particularly those interested in film history and experimental cinema, have embraced the film for its artistic merit and historical importance. The film's relatively short length and dynamic editing make it more accessible to contemporary viewers than many other experimental films of its era. Today, it enjoys cult status among cinephiles and continues to be discovered by new generations of film enthusiasts.

Awards & Recognition

- Named one of the 100 most important films of the 20th century by Cahiers du Cinéma

- Preserved in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress (cultural significance recognition)

- Voted among the top 10 avant-garde films of all time by the International Film Critics Association

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet montage cinema (particularly Eisenstein and Vertov)

- Surrealist art and literature

- French Impressionist cinema of the 1920s

- Dadaist anti-art movement

- Documentary tradition of Robert Flaherty

- German Expressionist cinema

- The city symphony film genre

- Photography of Eugène Atget

- Literary works of Marcel Proust

- Political cinema of the Soviet Union

This Film Influenced

- Man with a Movie Camera (1929) - mutual influence with Vertov

- The Blood of a Poet (1930) - Cocteau's surrealism

- Chronicle of a Summer (1961) - Rouch's direct cinema

- Breathless (1960) - Godard's jump cuts

- Weekend (1967) - Godard's social satire

- Manhattan (1979) - Allen's city portrait

- Paris, Texas (1984) - Wenders' road documentary style

- Baraka (1992) - non-narrative documentary

- Koyaanisqatsi (1982) - visual essay film

- The Gleaners and I (2000) - Varda's personal documentary

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and restored by the Cinémathèque Française in collaboration with the Criterion Collection. The original negative was discovered in deteriorated condition in the 1960s and underwent extensive restoration in the 1990s. A digital restoration was completed in 2010 using advanced technology to repair damage and enhance image quality while preserving the original artistic intent. The restored version is now part of the permanent collections of major film archives worldwide, including the British Film Institute, the Museum of Modern Art, and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. The film is considered well-preserved compared to other works of its era, thanks to early recognition of its historical importance and dedicated preservation efforts.