Race Riot

Plot

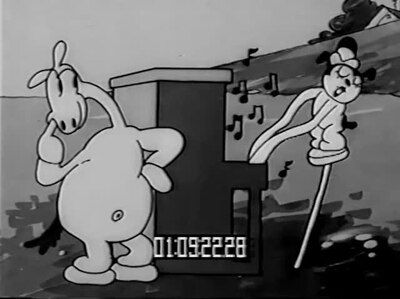

In this early Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoon, Oswald is determined to enter his horse in a prestigious horse race. To prepare his steed for competition, Oswald subjects him to an intensive training regimen that includes various exercises, all performed to the musical accompaniment of a pianist. The training sequences showcase the increasingly absurd and comical methods Oswald employs to get his horse into racing shape. As race day approaches, Oswald's unconventional training methods lead to chaotic and humorous situations. The film culminates in the actual race, where Oswald's horse faces off against competitors, with the training paying off in unexpected and hilarious ways.

Director

About the Production

This was one of Walter Lantz's first Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons after taking over production from Disney. The film was produced during the transition from silent to sound animation, featuring synchronized music and sound effects. The animation was created using traditional hand-drawn techniques on paper, with each frame drawn individually.

Historical Background

1929 was a pivotal year in cinema history, marking the complete transition from silent films to 'talkies.' The stock market crash of October 1929 also occurred during this period, beginning the Great Depression that would reshape the entertainment industry. Animation was rapidly evolving, with synchronized sound becoming the new standard. Disney had just introduced Mickey Mouse in 'Steamboat Willie' (1928), revolutionizing the medium. When Lantz took over Oswald, he was competing not only with Disney but also with other animation pioneers like Max Fleischer. The film reflects the era's fascination with sports and racing, which were popular entertainment forms during the Roaring Twenties.

Why This Film Matters

This cartoon represents an important transitional period in American animation history, marking Walter Lantz's assumption of the Oswald character and the establishment of his own animation studio. It exemplifies the rubber hose animation style that dominated late 1920s cartoons, characterized by fluid, exaggerated movements. The film also demonstrates the early integration of synchronized sound in animation, a technological advancement that would transform the medium. As one of the early sound cartoons, it helped establish conventions for musical accompaniment in animated shorts that would influence decades of animation. The preservation of such early works provides valuable insight into the evolution of animation techniques and storytelling.

Making Of

The production of 'Race Riot' marked a significant transition in animation history. Walter Lantz took over the Oswald series after a bitter dispute between Walt Disney and producer Charles Mintz, who controlled the character's rights through Universal. Lantz had to quickly establish his own style for the character while maintaining the elements that made Oswald popular. The animation team worked under intense pressure to produce cartoons that could compete with Disney's new Mickey Mouse character. The sound synchronization was achieved using the Phonofilm system, which was still relatively new technology. Animators worked on large animation discs, drawing each frame by hand on paper, with the horse training sequences requiring particularly careful timing to match the musical accompaniment.

Visual Style

The animation employs the standard black and white 35mm film format of the era, with careful attention to timing and movement. The camera work is relatively static, as was typical for early animation, focusing on the character movements within the frame. The training sequences feature dynamic compositions that maximize the comedic potential of Oswald's interactions with his horse. The visual style utilizes the rubber hose animation technique, with characters' limbs moving in fluid, exaggerated motions that defied realistic anatomy.

Innovations

The cartoon represents an early successful implementation of synchronized sound in animation, using the Phonofilm system. The timing of character movements to match musical accompaniment demonstrates sophisticated understanding of the new technology. The animation maintains consistent quality while incorporating the technical demands of sound synchronization. The fluid character movements showcase the advanced state of rubber hose animation techniques. The film also demonstrates effective use of limited animation techniques to maximize production efficiency without sacrificing visual quality.

Music

The film features a synchronized piano score that accompanies the action throughout, particularly during the horse training sequences. The music was likely composed by a studio musician and performed live during recording sessions. Sound effects include hoof beats, whistles, and other cartoon noises synchronized to the action. The soundtrack represents early experiments with matching music to animated action, a technique that would become standard in the industry. The pianist character within the cartoon serves as both a visual gag and a meta-reference to the importance of musical accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

No significant dialogue quotes survive from this silent-era cartoon with synchronized music

Memorable Scenes

- The extended sequence where Oswald trains his horse with increasingly absurd exercises while a pianist provides musical accompaniment, showcasing the rubber hose animation style and early sound synchronization techniques

Did You Know?

- This was Walter Lantz's first Oswald cartoon after Universal removed Disney from the project

- The film was released during the early sound era, making it one of the early Oswald cartoons with synchronized sound

- Oswald the Lucky Rabbit was originally created by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks before the rights were lost to Universal

- The pianist character in the film represents the growing importance of musical accompaniment in early sound cartoons

- The horse training sequences showcase the rubber hose animation style popular in the late 1920s

- This cartoon was part of Universal's attempt to compete with Disney's Mickey Mouse and Fleischer's Betty Boop

- The film's title 'Race Riot' was considered acceptable in 1929 but would be controversial today

- Walter Lantz would later become famous for creating Woody Woodpecker in 1940

- The animation was likely produced at the Universal Studios lot in the San Fernando Valley

- Only a few Oswald cartoons from this era survive in complete form today

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews from 1929 are scarce, but trade publications generally noted the technical achievement of the synchronized sound and the cartoon's comedic timing. Modern animation historians recognize 'Race Riot' as an important example of early sound animation and Lantz's early work. Critics today appreciate it as a historical artifact that shows the transition from Disney's to Lantz's interpretation of Oswald, though it's generally considered less innovative than Disney's work. The cartoon is valued by animation enthusiasts for its place in the development of American animation and its demonstration of early sound techniques.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1929 would have been impressed by the synchronized sound and the familiar Oswald character, though the transition from Disney's to Lantz's style may have been noticeable. The cartoon's physical comedy and musical elements were well-suited to the vaudeville-influenced humor popular at the time. Modern audiences primarily encounter this film through animation festivals and archival screenings, where it's appreciated for its historical significance and as an example of early sound animation techniques.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Disney's early Oswald cartoons

- Felix the Cat cartoons

- Vaudeville comedy routines

- Sports films of the 1920s

This Film Influenced

- Later Walter Lantz Oswald cartoons

- Early Woody Woodpecker cartoons

- Other sports-themed animation of the 1930s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in archives but is considered relatively rare. Some sources indicate that prints are held in animation collections and film archives, though it may not be widely accessible to the public. The survival rate for early Oswald cartoons is estimated at around 50%, making this a relatively well-preserved example from the era.