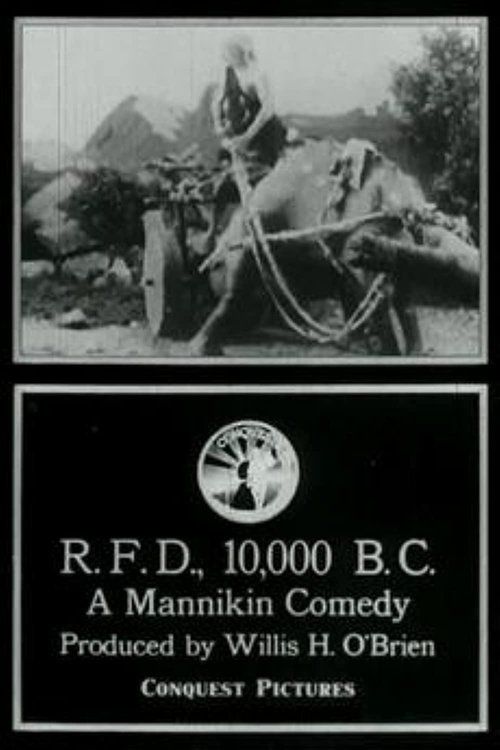

R.F.D., 10,000 B.C.

Plot

This pioneering stop-motion animation short presents a humorous take on prehistoric life, cleverly juxtaposing ancient times with modern concepts. The film follows the comedic adventures of cavemen attempting to establish a primitive postal service (R.F.D. - Rural Free Delivery) in 10,000 B.C., using dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures as their delivery vehicles. Through Willis O'Brien's innovative animation techniques, the story depicts the absurd challenges these early postal workers face as they try to deliver mail across treacherous prehistoric landscapes. The narrative culminates in a series of slapstick mishaps involving various dinosaurs, mammoths, and other prehistoric fauna interfering with the mail delivery attempts. The film serves as both entertainment and a showcase of O'Brien's emerging mastery of stop-motion animation.

Director

About the Production

This film represents one of Willis H. O'Brien's earliest professional works, created while he was still developing his revolutionary stop-motion techniques. The production utilized miniature models and articulated armatures for the prehistoric creatures, a technique O'Brien would perfect in later works. The Edison Company, already established as a leader in early cinema, provided O'Brien with the resources to experiment with this relatively new animation medium. The film's production involved creating detailed miniature sets representing prehistoric landscapes and crafting movable dinosaur models that could be positioned frame by frame. The title's clever wordplay suggests the film's comedic approach to historical accuracy.

Historical Background

The year 1917 represented a pivotal moment in both world history and the development of cinema. The United States had just entered World War I, which would dramatically impact all aspects of American life, including the film industry. Meanwhile, the film industry itself was undergoing massive transformation, with Hollywood emerging as the new center of American cinema and many East Coast studios, including Edison, beginning their decline. Technologically, 1917 saw animation still in its experimental phase, with techniques like stop-motion being pioneered by innovators like O'Brien. The Edison Manufacturing Company, once dominant in early cinema, was struggling to compete with newer West Coast studios. This film was created during the silent era, before synchronized sound became standard, meaning all comedy had to be visual. The prehistoric setting also reflected the contemporary fascination with dinosaurs and paleontology, which had captured public imagination following major fossil discoveries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Why This Film Matters

'R.F.D., 10,000 B.C.' holds immense cultural significance as one of the earliest surviving examples of American stop-motion animation featuring dinosaurs. This film represents a crucial stepping stone in the development of special effects in cinema, demonstrating that complex creature movements could be achieved through animation rather than live-action tricks. The work established Willis O'Brien as a pioneer who would later revolutionize film with 'The Lost World' and 'King Kong.' The film's comedic approach to prehistoric life also reflects early 20th-century attitudes toward science and history, often treating scientific subjects with humor and popular appeal. Its creation at Edison Studios connects it to the very birth of American cinema, as Thomas Edison's company was instrumental in developing film technology. The film's anachronistic premise (modern postal service in prehistoric times) exemplifies the creative freedom of early cinema, where filmmakers were not bound by historical accuracy but could freely mix time periods for comedic effect.

Making Of

The creation of 'R.F.D., 10,000 B.C.' marked a significant milestone in Willis H. O'Brien's development as a stop-motion animator. Working at the Edison Studios in the Bronx, O'Brien had to invent many of his techniques from scratch, as stop-motion animation was still in its infancy. The production involved painstaking work positioning miniature dinosaur models frame by frame, with each movement requiring multiple exposures. O'Brien likely built the creature models himself using articulated metal armatures that could be posed in different positions, then covered with modeling clay or rubber to give them texture and form. The sets were constructed in miniature scale to match the models, creating the illusion of a prehistoric world. The film's comedic premise allowed O'Brien to experiment with movement and timing, as the absurd scenarios of dinosaurs delivering mail provided perfect opportunities for slapstick animation. This early work laid the groundwork for the more sophisticated techniques O'Brien would develop for his later masterpieces.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'R.F.D., 10,000 B.C.' would have employed the standard techniques of silent-era filmmaking, adapted for stop-motion animation. The camera would have been mounted on a fixed tripod to maintain consistent framing between shots, crucial for the illusion of continuous movement in stop-motion. Lighting would have been carefully controlled to eliminate shadows and maintain consistent illumination across the hundreds of individual frames required for each sequence. The miniature sets would have been built to scale with the animated models, creating a believable world despite their small size. The cinematographer would have worked closely with O'Brien to ensure that each frame captured the subtle movements of the articulated models while maintaining the comedic timing of the action. The black and white film stock of the era would have provided high contrast, helping the miniature models stand out against their backgrounds. The camera work likely included simple pans and follows to track the movement of the animated creatures across the sets.

Innovations

This film represents several important technical achievements in early cinema and animation history. The primary innovation was O'Brien's development of articulated armatures for his dinosaur models, allowing for more realistic and varied movements than previous animation techniques. The film demonstrated that complex creature animation could be achieved through stop-motion rather than the more common cut-out or cel animation methods of the period. The production also pioneered techniques for combining miniature sets with animated figures, creating a believable world despite the scale differences. O'Brien's work on this film helped establish the foundation for the more sophisticated animation systems he would later develop. The film's successful integration of comedy with technical innovation showed that special effects could serve storytelling rather than merely demonstrating technical prowess. The production also represented an early example of using animation for comedic purposes rather than just educational or abstract content, expanding the medium's artistic possibilities.

Music

As a silent film from 1917, 'R.F.D., 10,000 B.C.' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibitions. The typical score would have been performed by a theater pianist or small orchestra, using popular musical cues of the era to enhance the comedy and action. The music would have been lively and upbeat during the slapstick sequences, with more dramatic or mysterious themes when the dinosaurs appeared. The Edison Company often provided suggested musical cues with their films, indicating where theaters should use specific types of music. The soundtrack would have relied heavily on well-known classical pieces adapted for comedic effect, along with popular songs of the period. The absence of synchronized dialogue meant that all storytelling had to be visual, with the music providing emotional context and timing for the animated action. The musical accompaniment would have been essential in creating the film's comedic atmosphere and helping audiences understand the narrative without spoken words.

Famous Quotes

No known surviving quotes from this lost film

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence establishing the absurd premise of a prehistoric postal service, with cavemen attempting to organize mail delivery using dinosaur-drawn carts; The climactic chase scene involving a Tyrannosaurus Rex interfering with mail delivery, showcasing O'Brien's early mastery of creature animation; The comedic sequence where smaller dinosaurs are used as living mailboxes, demonstrating the film's creative approach to prehistoric problem-solving

Did You Know?

- This film represents one of the earliest examples of Willis H. O'Brien's stop-motion work, predating his more famous films like 'The Lost World' (1925) and 'King Kong' (1933)

- The title 'R.F.D., 10,000 B.C.' creates an anachronistic joke by combining Rural Free Delivery (a modern postal service) with prehistoric times

- O'Brien was only in his mid-20s when he created this film, demonstrating his early mastery of complex animation techniques

- The Edison Manufacturing Company, founded by Thomas Edison, was one of the earliest film production companies in America

- This film is considered lost or extremely rare, with no known complete copies surviving in major film archives

- The film was part of Edison's series of comedy shorts that often featured fantastical or impossible scenarios

- O'Brien's work on this film helped establish stop-motion animation as a viable technique for feature films

- The prehistoric creatures in the film were likely created using articulated armatures covered with rubber or clay

- This film represents an important transitional work between early simple animations and the more sophisticated creature effects O'Brien would later create

- The Edison Company was already in decline by 1917, making this one of their later productions before the studio closed

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'R.F.D., 10,000 B.C.' is difficult to document due to the film's age and rarity, but trade publications of the era generally praised Edison's comedy shorts for their innovation. The Motion Picture News and other industry journals likely noted the novelty of the stop-motion technique, which was still relatively unknown to general audiences. Modern film historians and animation scholars recognize the film as an important early work in O'Brien's career, though its status as a lost or extremely rare film has prevented comprehensive critical analysis. Animation historians consider it a significant precursor to more sophisticated stop-motion works, noting how it demonstrates O'Brien's early experimentation with the medium. The film is often mentioned in scholarly discussions about the evolution of special effects and the development of dinosaur imagery in cinema, though its limited availability has prevented detailed critical evaluation.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1917 would have been one of wonder and amusement, as stop-motion animation was still a novelty to most moviegoers. The combination of dinosaurs and comedy would have been particularly appealing to audiences of the time, who were fascinated by both prehistoric creatures and slapstick humor. The film's short length and straightforward visual comedy would have made it popular as part of theater programs that included multiple shorts. Modern audiences have had limited opportunity to view the film due to its rarity, but film enthusiasts and animation historians express great interest in this early work. The film's status as a lost title has created a certain mystique among cinema buffs, who recognize its importance in the development of special effects despite being unable to view it directly. Those who have studied O'Brien's work consider it an essential piece in understanding his artistic development.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Edison Company comedy shorts

- Early animation experiments

- Slapstick comedy tradition

- Paleontological discoveries of the era

- Silent film comedy techniques

This Film Influenced

- The Dinosaur and the Missing Link: A Prehistoric Tragedy (1917)

- The Ghost of Slumber Mountain (1918)

- The Lost World (1925)

- King Kong (1933)

- Mighty Joe Young (1949)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Considered lost or extremely rare. No complete copies are known to exist in major film archives including the Library of Congress, UCLA Film & Television Archive, or the Museum of Modern Art. The film may exist only in fragments or as lost footage, as many Edison Company films from this period were destroyed or deteriorated due to the unstable nitrate film stock used in the era. Some film historians hold hope that copies may exist in private collections or in archives that have not yet been fully catalogued.