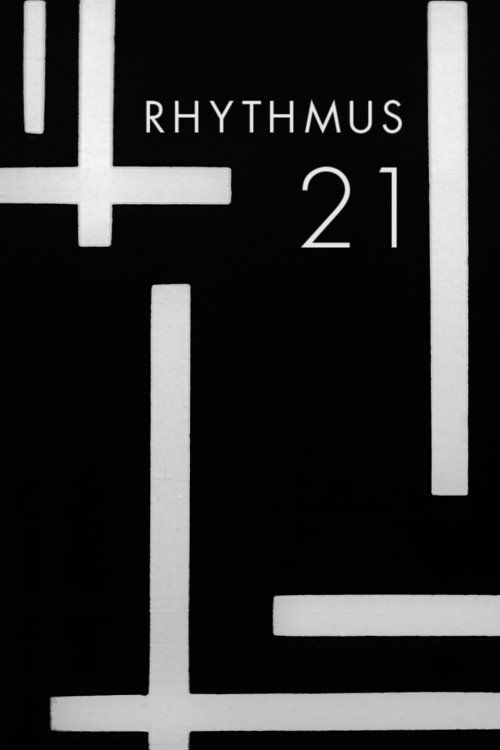

Rhythm 21

Plot

Rhythm 21 is a groundbreaking abstract animated short film that presents a dynamic visual symphony of geometric forms. The film consists entirely of black, white, and grey squares and rectangles that appear, disappear, grow, shrink, and move across the screen in precise, rhythmic patterns. These simple shapes dance and interact in complex ways, creating a sense of movement, depth, and musicality without any representational imagery. The composition follows mathematical principles, with the shapes appearing to pulse and breathe in a carefully choreographed sequence that explores the pure visual properties of form, contrast, and motion. The film represents a radical departure from traditional narrative cinema, instead focusing on the emotional and aesthetic impact of abstract visual elements arranged in time.

Director

About the Production

Rhythm 21 was created using paper cutouts and stop-motion animation techniques. Richter meticulously cut squares and rectangles from paper and photographed them frame by frame, moving and repositioning them between each exposure. The film was shot on 35mm black and white film stock, with the black background created by leaving portions of the frame unexposed. Richter's approach was influenced by his background in painting and his involvement with the Dada movement, treating the film strip as a canvas for temporal rather than spatial composition. The production was extremely labor-intensive, requiring precise measurements and movements for each frame to achieve the mathematical precision of the final composition.

Historical Background

Rhythm 21 was created during the Weimar Republic, a period of intense artistic and political upheaval in Germany. The early 1920s saw the rise of numerous avant-garde movements, including Dadaism, Bauhaus, and Constructivism, all challenging traditional artistic forms. Germany was also a world leader in film production during this era, with Berlin being a major center of cinematic innovation. The film emerged from the Dada movement's rejection of traditional art forms and bourgeois values, seeking instead to create new modes of expression that reflected the chaos and fragmentation of post-World War I society. The abstract nature of the film can be seen as a response to the disillusionment with representational art after the trauma of war. Additionally, this was a period when artists across disciplines were exploring the concept of 'synesthesia' - the blending of senses - and Richter's attempt to create 'visual music' was part of this broader artistic exploration. The film also coincided with early developments in abstract art, with artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian exploring similar ideas in painting.

Why This Film Matters

Rhythm 21 represents a pivotal moment in the history of cinema, marking one of the first successful attempts to create purely abstract animation. The film demonstrated that cinema could be used as a medium for abstract art, not just for storytelling or documentation. It helped establish animation as a serious artistic medium beyond entertainment, influencing generations of experimental filmmakers. The film's mathematical precision and rhythmic structure prefigured later developments in computer animation and digital art. Its influence can be seen in music videos, motion graphics, and contemporary digital art. The film also represents an important early example of cross-disciplinary artistic collaboration, bridging the worlds of visual art, music, and emerging cinema technology. Rhythm 21 has been studied extensively in film schools and art history programs as a foundational work of abstract cinema. Its preservation and continued screening at film festivals and museums demonstrate its enduring relevance to contemporary artists and audiences interested in the intersection of technology and art.

Making Of

Hans Richter created Rhythm 21 during his intense involvement with the Berlin Dada movement, where artists were exploring radical new forms of expression across all media. The film emerged from Richter's experiments with 'scroll paintings,' where he would paint continuous abstract compositions on long rolls of paper. He realized that these could be animated by photographing sections sequentially. The production process was incredibly meticulous - Richter would spend hours calculating the precise movements of each shape, using graph paper to plan the sequences. He worked alone in his Berlin studio, often late at night, using basic animation equipment he modified himself. The film was shot on a hand-cranked camera, with Richter having to maintain perfect consistency in his frame-by-frame movements. The lack of commercial pressure allowed him to experiment freely, and he viewed the film as a 'visual music' that could express emotions and ideas without relying on narrative or representational imagery. Richter later described the creative process as 'painting with time itself,' emphasizing how the medium of film allowed him to explore rhythm and movement in ways impossible in static painting.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Rhythm 21 is characterized by its extreme minimalism and mathematical precision. Shot on 35mm black and white film, the entire composition consists of geometric shapes against a black background, with no camera movement or traditional cinematic techniques. The 'cinematography' was achieved through stop-motion animation, with each frame carefully composed to create the illusion of movement. Richter used high-contrast lighting to create sharp edges and clear distinctions between the shapes and background. The film demonstrates remarkable control of exposure, maintaining consistent tonal values throughout despite the technical challenges of stop-motion photography. The visual rhythm is created through careful variation in the size, position, and timing of the shapes, with some movements occurring rapidly while others unfold slowly. The cinematography serves the film's musical concept, with visual elements functioning like notes in a composition, creating patterns of tension and release through their arrangement and timing.

Innovations

Rhythm 21 pioneered several technical innovations in animation and filmmaking. It was one of the first films to use stop-motion animation for abstract purposes rather than for creating the illusion of life in inanimate objects. Richter developed techniques for creating perfect geometric shapes on film, using masks and multiple exposures to achieve crisp edges and precise positioning. The film demonstrated how mathematical principles could be applied to temporal composition, prefiguring computer animation by several decades. The precise control of timing and rhythm in the film was technically groundbreaking for its era, requiring extreme consistency in frame-by-frame animation. Richter also experimented with film's ability to create illusions of depth and movement through simple two-dimensional shapes, techniques that would later be fundamental to motion graphics and computer animation. The film's preservation of pure black and white tones without degradation was also technically impressive for the time.

Music

Rhythm 21 was originally created as a silent film during the era before synchronized sound was practical. However, Richter conceived of it as a 'visual music' and intended for it to be screened with musical accompaniment. Early screenings featured live musical performances, often with experimental compositions by contemporary composers. Over the decades, various musicians have created scores for the film, ranging from classical piano pieces to electronic music. Notably, composer Pierre Boulez created a score for it in the 1960s, and more recently, electronic artists have composed new soundtracks. The absence of an original soundtrack has actually contributed to the film's longevity, as each new musical interpretation offers a fresh perspective on the visual rhythms. Some modern screenings feature no music at all, allowing audiences to focus purely on the visual rhythms and the ambient sounds of the screening environment.

Famous Quotes

"I wanted to create a visual music, a composition for the eyes that would work in the same way as a musical composition works for the ears." - Hans Richter

"Film is not just a recording medium, it's a medium for creating new realities." - Hans Richter

"In Rhythm 21, I tried to paint with time itself, to make the invisible visible." - Hans Richter

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where a single white square appears and begins to pulse rhythmically against the black background, establishing the film's visual language and musical rhythm. This simple yet powerful introduction immediately signals to viewers that they are watching something entirely new and different from conventional cinema.

Did You Know?

- Rhythm 21 is considered one of the very first abstract animated films ever created, predating more famous works like Oskar Fischinger's films

- The film was originally titled 'Rhythmus 21' in German, reflecting its mathematical and musical approach to visual composition

- Hans Richter created a series of 'Rhythm' films, with Rhythm 21 being the first, followed by Rhythm 23 (1923) and Rhythm 25 (1925)

- The film was created using only three colors: black, white, and grey, demonstrating how complex visual effects could be achieved with minimal elements

- Richter was inspired by the musical compositions of his contemporary, composer Ferruccio Busoni, and sought to create a visual equivalent of musical rhythm

- The film was initially shown in avant-garde art galleries and Dadaist gatherings rather than traditional cinemas

- Each movement in the film was precisely calculated using mathematical proportions based on the golden ratio

- The film was created before the development of optical sound, so it was originally screened without any musical accompaniment, though later screenings have featured various musical scores

- Richter's technique influenced later abstract animators, including Norman McLaren and Len Lye

- The film was preserved and restored by the Academy Film Archive in 2012 as part of their Avant-Garde Film collection

What Critics Said

Initial critical reception to Rhythm 21 was mixed but largely confined to avant-garde art circles rather than mainstream film criticism. Dadaist publications praised its radical departure from traditional cinema, with critics calling it 'a new language for the eyes' and 'the purest form of cinematic art.' However, mainstream film critics of the era were often confused or dismissive, with some questioning whether it could even be considered a 'film' in the traditional sense. Over time, critical opinion has shifted dramatically, and the film is now universally recognized as a masterpiece of abstract cinema. Modern critics have praised its mathematical precision, rhythmic complexity, and pioneering role in establishing animation as an art form. The film has been the subject of numerous scholarly articles and books, with critics analyzing its relationship to musical theory, mathematics, and contemporary art movements. Contemporary critics often describe it as 'astonishingly modern' and note how its minimalist approach achieves complex emotional and aesthetic effects.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception was limited to small gatherings of artists and intellectuals in Berlin's avant-garde circles. Many viewers were initially confused by the film's complete lack of narrative or representational content, though some reported experiencing a hypnotic or trance-like state while watching. The film's abstract nature meant it didn't appeal to general cinema audiences of the 1920s, who were accustomed to narrative films. However, among artistic and intellectual circles, it generated intense discussion and debate about the nature of cinema and its potential as an art form. Modern audiences encountering the film in museums, film festivals, or online often report finding it surprisingly engaging and meditative, with many noting its contemporary feel despite being nearly a century old. The film has found new life on digital platforms, where it has been viewed millions of times by audiences interested in experimental art and animation history.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Wassily Kandinsky's abstract paintings

- Ferruccio Busoni's musical theories

- Dadaist artistic principles

- Bauhaus design concepts

- Constructivist art movement

- Contemporary musical compositions

- Scroll painting techniques

- Mathematical proportion theories

This Film Influenced

- Rhythm 23 (1923)

- Rhythm 25 (1925)

- Oskar Fischinger's abstract animations

- Norman McLaren's experimental films

- Len Lye's abstract animations

- Early computer animations

- Music video visuals

- Motion graphics design

- Abstract expressionist films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Rhythm 21 has been preserved by several major archives including the Academy Film Archive, the British Film Institute, and the Cinémathèque Française. The film underwent a major restoration in 2012 by the Academy Film Archive as part of their Avant-Garde Film collection, with original 35mm elements being scanned and digitally restored to remove deterioration while preserving the original contrast and detail. The restored version has been screened at numerous film festivals and museums. The film is also part of the National Film Registry, having been selected for preservation in 2016 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. Digital copies are maintained by various educational institutions and film archives worldwide.