Rip's Dream

Plot

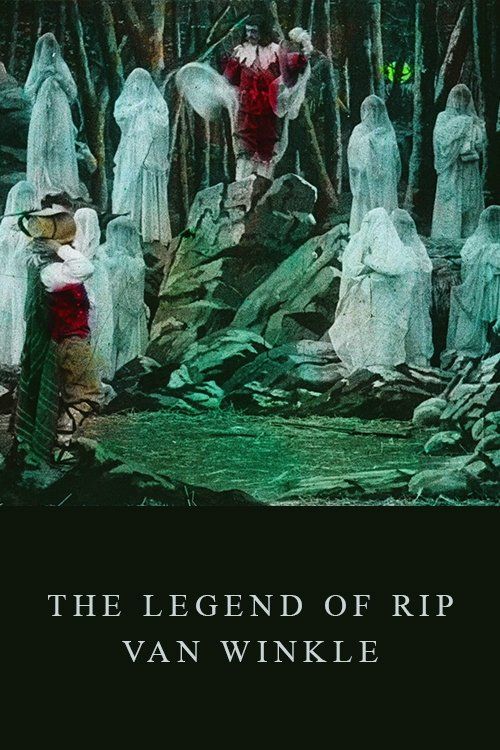

Georges Méliès' adaptation of the classic Rip Van Winkle tale follows a weary villager who falls asleep in the mountains and awakens twenty years later to find his world completely transformed. The film showcases Méliès' signature theatrical style with elaborate sets and magical transformations as Rip experiences the disorienting effects of time passage. Upon returning to his village, he discovers his wife has died, his children are grown, and he is a stranger in his own home. The dreamlike quality of the narrative allows Méliès to incorporate his trademark special effects, including dissolves, multiple exposures, and fantastical scenery changes. The story concludes with Rip's realization of his profound loss and the irreversible nature of time's passage.

Director

About the Production

Filmed entirely in Méliès' glass studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois, the production utilized his signature painted backdrops and theatrical stage machinery. The film employed multiple exposure techniques and substitution splices to create the magical transformation effects. Méliès himself played the lead role of Rip, while his son André appeared in supporting roles. The film was hand-colored frame by frame using stencils for special prints, a laborious process that Méliès reserved for his most important productions.

Historical Background

In 1905, cinema was still in its infancy, with films typically lasting only a few minutes and shown as part of variety programs. Méliès was one of the few filmmakers creating narrative fantasy films with sophisticated special effects. This period saw the rise of nickelodeons in America and the establishment of permanent cinemas across Europe. The film industry was transitioning from novelty to art form, with Méliès at the forefront of cinematic innovation. 1905 also marked the Russo-Japanese War and the beginning of the Russian Revolution, events that would influence global culture and cinema in the following years. Méliès' work represented the peak of French cinema's early dominance before American studios would later take the lead.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents Méliès' contribution to adapting literary works for the screen, helping establish cinema as a medium capable of narrative storytelling. It demonstrates the early cross-cultural exchange between American literature and European cinema, adapting Washington Irving's quintessentially American tale for French audiences. The film showcases Méliès' role in developing the language of cinema, particularly in visual storytelling and special effects. It exemplifies the transition from cinema as a technological novelty to an artistic medium capable of emotional depth and narrative complexity. The film also illustrates how early cinema drew from established literary traditions while creating its own visual language.

Making Of

Georges Méliès, a former magician and theater owner, brought his theatrical expertise to this adaptation of the American literary classic. The film was shot in his custom-built glass studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois, which allowed maximum natural light for filming. Méliès employed his innovative substitution splicing technique to create the magical effects showing Rip's transformation over twenty years. The production involved elaborate painted backdrops depicting both the idyllic mountain setting and the changed village. Méliès himself performed as Rip, drawing on his theatrical background to convey the character's confusion and despair. The film's creation coincided with Méliès' transition from pure trick films to more narrative-driven cinema, though it still showcases his signature special effects throughout.

Visual Style

The film employed Méliès' characteristic theatrical cinematography, with static camera positions capturing stage-like compositions. The visual style featured elaborate painted backdrops and detailed props creating a fantastical interpretation of the Hudson Valley setting. Méliès used multiple exposure techniques to show spectral images and transformations, while substitution splices created magical effects. The hand-colored versions featured vibrant blues and reds, enhancing the dreamlike quality of the narrative. The cinematography emphasized theatrical depth through forced perspective and careful blocking of actors within the limited studio space.

Innovations

The film showcased Méliès' pioneering use of multiple exposure to create ghostly images and temporal effects. His substitution splicing technique allowed for seamless magical transformations, particularly in scenes showing the passage of time. The production utilized sophisticated painted backdrops and theatrical machinery to create convincing illusions of depth and movement. Méliès also employed early matte painting techniques to extend sets beyond the physical confines of his studio. The film's hand-colored versions demonstrated advanced stencil coloring techniques that were labor-intensive but visually striking.

Music

As a silent film, 'Rip's Dream' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during exhibition. The typical score would have been provided by a pianist or small orchestra using classical and popular pieces of the era. Méliès often provided suggested musical cues with his films, indicating appropriate moods for different scenes. The music would have emphasized the film's emotional moments, particularly Rip's confusion and despair upon awakening. No original score or specific musical arrangements for this film survive.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue)

Memorable Scenes

- The magical transformation sequence where Rip ages twenty years in his sleep, utilizing Méliès' signature multiple exposure technique to show the rapid passage of time through spectral overlays and set changes

Did You Know?

- This film was cataloged as Star Film No. 638-639 in Méliès' production catalog

- The film was originally titled 'Le Rêve de Rip' in French

- Méliès created this during his most prolific period, producing over 50 films in 1905 alone

- The film featured Méliès' patented multiple exposure technique to show the passage of time

- Hand-colored versions of the film exist, showing Méliès' attention to visual detail

- The sets were designed to resemble the Hudson Valley setting of Washington Irving's original story

- Méliès' son André, who was around 16 at the time, appears in the film

- The film was distributed internationally through Méliès' extensive distribution network

- This was one of Méliès' later narrative films, as he began moving away from pure trick films

- The original negative is believed to be lost, surviving only through prints made for distribution

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in early film trade publications praised Méliès' technical innovations and imaginative approach to the classic story. Critics noted the effectiveness of his special effects in conveying the passage of time and the emotional impact of Rip's awakening. Modern film historians recognize the work as an important example of early narrative cinema and Méliès' evolving artistic vision. The film is studied today for its place in the development of cinematic storytelling and its demonstration of Méliès' mastery of early special effects techniques.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th century audiences reportedly enjoyed the film's magical effects and emotional story, which stood out among the simpler actualities and trick films of the era. The familiar story of Rip Van Winkle, combined with Méliès' spectacular visual effects, made the film popular in both French and international markets. The film's emotional resonance with themes of time, loss, and alienation connected with audiences experiencing rapid technological and social changes. Contemporary viewers appreciated Méliès' ability to create a complete narrative world within the constraints of early cinema technology.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Washington Irving's 'Rip Van Winkle' (1819)

- European theatrical traditions

- Stage magic and illusion

- German Romantic literature

- French literary adaptations

This Film Influenced

- Later adaptations of Rip Van Winkle

- Fantasy narrative films of the 1910s

- Time passage films

- Dream sequence cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in various archives, including the Cinémathèque Française and the Museum of Modern Art. Some prints exist in black and white, while rare hand-colored versions are preserved in select collections. The original camera negative is believed lost, as with most of Méliès' work. The film has been digitally restored by several archives and is available through curated collections of Méliès' films.